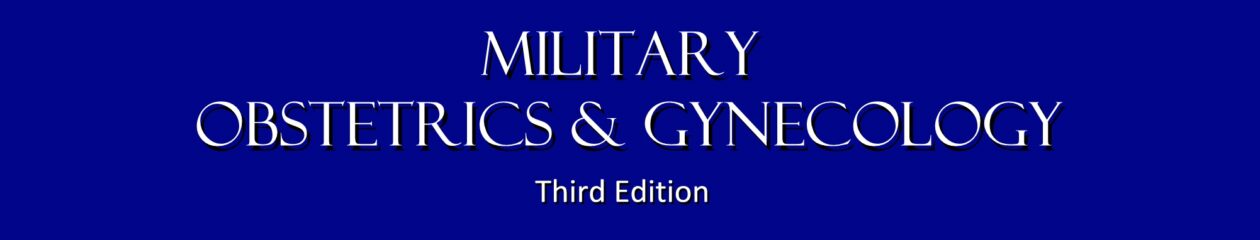

The opening of the uterus is called the cervix.

While the cervix is considered a portion of the uterus, it is functionally and histologically quite different. It is composed of dense connective tissue, with very little smooth muscle. The body of the uterus, in contrast, is primarily smooth muscle.

The CervixThe cervix is located at the top of the vagina and is easily visualized by inserting a vaginal speculum fully into the vagina and opening the blades. The firm, smooth, pink structure appearing at the end of the vagina is the cervix.

The cervix is of clinical significance because of:

- The role it plays in pregnancy, remaining tightly closed for the bulk of gestation, then, at just the right time, thinning and opening to allow for birth of the baby.

- It’s vulnerability to cervical dysplasia and, by extension, cancer of the cervix, and

- The occasional patient who experiences symptoms of cervicitis, primarily painful intercourse and vaginal discharge.

Nabothian Cysts

Two normal anatomic variations are responsible for considerable clinical concern among the less experienced who examine women, Nabothian cysts and cervical ectropion.

Nabothian cysts from when the secretions from functional glandular epithelium become trapped below the surface of the skin. This can occur because of the normal deep infolding of the endocervical epithelium. It also may occur when the squamous exocervical epithelium covers over the mucous-producing endocervical epithelium (squamous metaplasia). It is seen more commonly after childbirth and sometimes occurs concomitantly with cervicitis.

Clinically, Nabothian cysts are seen or felt as firm nodules on the cervix. If close to the surface, they care clearly seen as cystic. If the diagnosis is in doubt, puncturing them will release clear, mucoid material. It is not necessary to do this, however, as the diagnosis is rarely in doubt.

Sometimes, particularly if large, Nabothian cysts will be seen to have a significant blood vessel or two coursing over the surface. These are of no concern, though if tampered with, they may bleed.

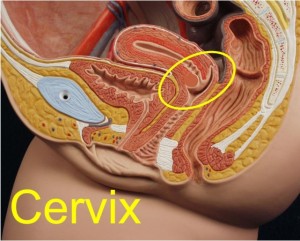

Cervical Ectropion

Inexperienced examiners are sometimes frightened to see a large, red, somewhat friable lesion occupying the central portion of the cervix and surrounding the cervix.

This is not a lesion…it is cervical ectropion.

The red color is from the shallow, vascular, mucous-producing endocervical epithelium which has grown out onto the face (exterior portion) of the cervix.

Over time, the ectropion may enlarge or diminish in size, as the squamocolumnar junction changes its relative position on the cervix. With pregnancy, the cervix tends to evert, making the ectropion larger. In menopause, the SQJ tends to recede back up the cervical canal, making the ectropion get progressively smaller before disappearing completely.

The fact that a cervical ectropion is present is of no clinical concern. It needn’t be treated and can safely be ignored.

If the ectropion is causing symptoms (eg., post-coital bleeding), or in the presence of recurrent cervical infections (cervicitis), then the ectropion can be treated by any means that safely eliminates the most superficial layer of cells, facilitating the inward growth of the surrounding squamous mucosa. Among these treatments are cryosurgery, chemical cautery (AgNO3), electrocautery, thermal cautery, LEEP, and laser ablation.

Cervicitis

CervicitisCervicitis means an infection of the cervix. This usually involves the glandular elements (columnar epithelium) of the cervix and is usually caused by organisms found in the vagina. Sometimes it is caused by such sexually transmitted diseases as chlamydia or gonorrhea. Most cases of cervicitis are unnoticed by the patient, but some notice painful intercourse, persistent vaginal discharge, aching pelvic pain or menstrual cramps.

The diagnosis can be confirmed by palpation of the cervix. Normally, this doesn’t hurt, but in the case of cervicitis, compression or movement of the cervix causes some discomfort. When clinically warranted, testing for STDs can be helpful before initiating treatment. If found, they should be individually treated.

A simple course of oral antibiotics can be effective at resolving the cervicitis, although if there is extensive cervical ectropion, the cervicitis may return. For recurrent cervicitis, some form of cervical ablation is usually needed, in addition to a short course of antibiotics, to permanently resolve the problem.

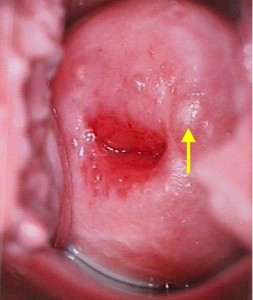

Condyloma

Condyloma acuminata, (venereal warts) are caused by a virus known as “Human Papilloma Virus” (HPV).

HPV is a sexually-transmitted virus which usually causes no symptoms but occasionally causes warts. The virus spreads throughout the skin of the vulva, vagina and cervix (as well as the inner thighs and lower abdomen), where it disappears into the skin cells and usually remains dormant forever.

Like many other viruses, if the patient’s immune system allows the virus to grow, it can reappear and cause warts. This virus is extremely common, infecting as many as 1/3 of the adult, sexually-active population. There is no known way to eliminate the virus from all skin cells.

There are two categories of warts, clinical and subclinical. Clinical warts appear as tiny, cauliflower-like, raised lesions around the opening of the vagina or inside the vagina. These lesions appear flesh-colored or white, are not tender and have a firm to hard consistency. If they are on the outside of the vagina or vulva, they are generally symptomatic, causing itching, burning, and an uncomfortable sensation during intercourse. If they are inside the vagina, they generally cause no symptoms.

The second category, subclinical warts, are invisible to the naked eye, are flat and colorless. They usually do not cause symptoms, although they may cause similar symptoms to the raised warts. These subclinical warts can be visualized if the skin is first soaked for 2-3 minutes with vinegar (3-4% acetic acid) and then viewed under magnification (4-10X) using a green or blue (red-free) light source.

Venereal warts are not dangerous and have virtually no malignant potential. Clinical warts may be a nuisance and so are usually treated. Subclinical warts are usually not treated since they are not a nuisance (most people with subclinical warts are unaware of their presence).

Patients with HPV are contagious to others, but there is no effective way to prevent its spread. Some physicians recommend condoms, but because the virus is found in areas of the skin beyond the condom, this is not likely to be effective. Some physicians recommend aggressive treatment of all warts, in the belief that active warts are more contagious than inactive virus within the skin. This theory has not, so far, been proven to be true.

Dysplasia

While warts are not considered dangerous, HPV infection is associated with another skin change known as “dysplasia.” Dysplasia means that the skin (mainly of the cervix) begins growing faster than it should. There are different degrees of dysplasia: mild, moderate and severe. None of these is malignant, but it is true that the next step beyond severe dysplasia is cancer of the cervix.

About 1/3 of all adult, sexually-active women have been infected with HPV, but probably less than 10% will ever develop dysplasia . Most (90%) of those with dysplasia will have mild dysplasia which will either regress back to normal or at least will never progress to a more advanced stage.

Most women with moderate to severe dysplasia of the cervix, if left untreated, will ultimately develop cancer of the cervix. If treated, most of these abnormalities will revert to normal, making this form of cervical cancer largely preventable.

Cervical dysplasia is usually a slowly-changing clinical problem. There is indirect evidence to suggest that on average, it takes about 10 years to advance from normal, through the various stages of dysplasia, and into cancer of the cervix. Of course, any individual may not follow these rules. In providing medical care to women with cervical dysplasia, good follow-up is important, but urgent medical evacuation is usually not indicated for less threatening categories of dysplasia.

In any patient with venereal warts (condyloma), you should look for possible dysplasia of the cervix. This is best done with colposcopy, but a simple Pap smear can be very effective. Because HPV causes warts and is also associated with dysplasia, more frequent Pap smears (every 6 months) is a wise precaution, at least initially.

If dysplasia is found, gynecologic consultation will be necessary, although this may be safely postponed for weeks or months if operational requirements make consultation difficult.

Cervical Cancer

Invasive cancer of the cervix is a relatively uncommon malignancy among women, representing about 2% of all new cancers. This is in contrast to the more common female cancers (breast 30%, lung 13%, colon 11%). It is less common than uterine (6%). ovarian (4%), and bladder (3%) cancer.

Pap smear screening has had a dramatic impact on the incidence of cervical cancer. Initially throught to promote early diagnosis of cervical cancer, Pap screening has been most helpful in detecting the pre-malignant changes that, when treated, are effective in preventing the actual development of cervical cancer. Most cases of invasive cervical cancer occur among women who have not been screened with Pap smears or who have not had a Pap smear in many years.

Those at increased risk for cervical neoplasia include women with multiple sexual partners, HPV infection (particularly the high risk HPV types), cigarette smokers and those with impaired immune systems.

The most common symptom of cervical cancer is abnormal vaginal bleeding, either spontaneous or provoked by intercourse or vigorous physical activity. In advanced cases, some patient will notice back or flank pain provoked by ureteral obstruction and hydronephrosis.

The diagnosis is usually confirmed by biopsy, but is suspected if a friable, visible, exophytic lesion is seen on the cervix. Endophytic lesions tend to invade deeply into the cervical stroma, creating an enlarged, firm, barrel-shaped cervix. Initial metastases are to the parametrial tissues and lymph nodes. Later, in addition to aggressive local spread into the upper vagina, rectum and bladder, hematogenous spread to the liver, lungs, and bone occurs.

Following diagnosis of cervical cancer, staging of the cancer is performed to assist in selecting the best treatment. Stages (0-IV) are defined by the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics, and include:

|

Stage |

Extent of Disease |

5-Year Survival Rates |

|

0 |

Carcinoma in situ, limited to the epithelium, without invasion |

>99% |

|

I |

Cancer limited to the cervix |

70%-99% |

|

II |

Cancer extends beyond the cervix, but not to the pelvic sidewall, and not to the lower third of the vagina |

60% |

|

III |

Cancer extends to the pelvic sidewalls and/or to the lower third of the vagina. |

45% |

|

IV |

Cancer extends beyond the true pelvis, or extends into the bladder or bowel mucosa. |

18% |

In addition, there are subcategories within each stage.

Treatment can consist of surgery, radiation therapy, and sometimes adjuvant therapy. The best option for treatment depends on the stage of the cancer. Surgery seems to work best on Stages I and IIA (no obvious parametrial involvement). Radiotherapy seems to work better for more advanced stages. Complications of either approach include bladder and bowel fistula formation, and loss of vaginal length.