Breech delivery is the single most common abnormal presentation.

The incidence is highly dependent on the gestational age. At 20 weeks, about one in four pregnancies are breech presentation. By full term, the incidence is about 4%.

Other contributing factors include:

- Abnormal shape of the pelvis, uterus, or abdominal wall,

- Anatomical malformation of the fetus,

- Functional abnormality of the fetus, and

- Excessive amniotic fluid (polyhydramnios).

Types of Breech Presentation

Breech babies can present in a variety of ways, including buttocks first, one leg first or both legs first.

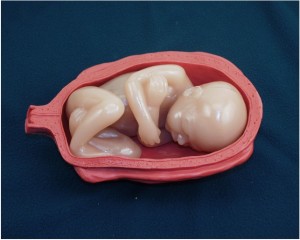

Frank breech means the buttocks are presenting and the legs are up along the fetal chest. The fetal feet are next to the fetal face. This is the safest arrangement for breech delivery.

Footling breech means either one foot (“Single Footling”) or both feet (“Double Footling”) is presenting. This is also known as an incomplete breech.

Complete breech means the fetal thighs are flexed along the fetal abdomen, but the fetal shins and feet are tucked under the legs. The buttocks is presenting first, but the feet are very close. Sometimes during labor, a complete breech will shift to an incomplete breech if one or both of the feet extend below the fetal buttocks.

Risks of Vaginal Breech Delivery

While all vaginal breech deliveries involve some degree of increased risk, footling breech deliveries are the most dangerous. They are notably associated with an increased risk of:

- Umbilical cord prolapse, and

- Delivery of the feet through an incompletely dilated cervix, leading to arm or head entrapment.

In cephalic presentations, the head fits very well into the lower uterine segment and usually physically blocks the umbilical cord from falling out before the fetus. Umbilical cord prolapse occurs more frequently with breeches because the breech often does not fit as well into the lower uterine segment very well. The risk of prolapsed cord is somewhat increased for frank breech, increased more for complete breech, and significantly increased for footling breech.

Head entrapment occurs when the smaller body of the fetus passes through the cervix before it is completely dilated, leaving the larger fetal head trapped behind an incompletely dilated cervix. This can be a big problem, since the umbilical cord is usually occluded at that point by the head wedged into the lower uterine segment. It is more likely to occur the more premature the fetus. Younger fetuses tend to have larger heads in proportion to their torsos. At 36 weeks, the heads and torsos are approximately the same size. After 36 weeks, the proportions steadily reverse and by full term, the fetal heads are smaller than the fetal torso.

In general, vaginal breech delivery poses more risks for the fetus than cesarean section. These risks include both asphyxial injury and mechanical injury to the fetus as it is delivered. Because of these risks, some physicians deliver most or all their breech babies a by cesarean section. Other physicians will attempt vaginal breech delivery if:

- He/she is experienced with vaginal breech deliveries and their complications,

- The overall risk environment is low, and

- The informed mother desires this over cesarean section.

It’s difficult to quantify how much experience and how current that breech experience should be. Many well-trained obstetricians will deliver 100 babies a year. Of those, about 4 of them will be breech. Half of those will likely be delivered by cesarean section because of high-risk factors. One more will probably be delivered by cesarean because the mother prefers cesarean delivery. For this initially well-trained obstetrician, continuing vaginal breech delivery experience may only occur once a year. It may prove difficult for that obstetrician’s skills to remain current under these circumstances.

Risk Factors

Factors that are often considered when contemplating a vaginal breech delivery include:

- Size of the fetus (not too small and not too large)

- Size of the maternal pelvis (the larger the better)

- Previous vaginal births (more is better)

- Previous vaginal breeches (more is better)

- Gestational age (not too old and not too young)

- Presentation (Frank breech is best, but complete breech is better than footling breech)

- Position of the fetal head (flexed is good, deflexed is very bad, neutral position is in-between)

- Electronic fetal monitor tracing of labor (normal is good, non-reassuring is bad).

- Progress in labor (normal progress is good, slow progress is bad)

- Availability of resources (immediate presence of anesthesia, OR, nursing, pediatrics, etc. is good, possibly delayed is bad)

- Enthusiasm of the informed mother for vaginal breech (very enthusiastic is good, not so enthusiastic is bad)

Spontaneous Breech Delivery

The simplest breech delivery is called a spontaneous breech.

The mother pushes the baby out with the normal bearing down efforts and the baby is simply supported until it is completely free of the birth canal. These babies pretty much deliver themselves.

This works best with smaller babies, mothers who have delivered in the past, and frank breech presentation.

Assisted Breech Delivery

If the breech baby gets stuck half-way out, or if there is a need to speed the delivery, an “assisted breech” delivery may be necessary. For this type of delivery, it is very helpful to have:

- At least one qualified assistant,

- An anesthetist or anesthesiologist in the event general anesthesia is needed, and

- Someone skilled in neonatal resuscitation other than yourself.

The wisest of obstetricians has these individuals present for all breech deliveries.

Make sure you have a generous episiotomy. This will give you more room to work, but may be unnecessary if the vulva is very stretchy and compliant. Otherwise, you can make an episiotomy, enlarge a pre-existing episiotomy, surgically (with scissors) extend a pre-existing perineal laceration, or make a second episiotomy. Some physicians will intentionally extend an episiotomy into the rectum (“proctoepisiorrhaphy”) because it gives them lots of room, is relatively easy to repair after the delivery, and rarely leads to any long-term problems for the mother.

Grasp the baby so that your thumbs are over the baby’s hips. If you grasp the baby any higher than that, there is some risk of injury to the fetal kidneys and abdominal organs.

If the baby is not facing “face down,” gently rotate the torso so the baby is face down in the birth canal (facing toward the maternal recutm).

Wrap a towel around the hips and legs. It will provide a more secure grip and will keep the legs secure and out of the way.

Have your assistant apply suprapubic pressure to keep the fetal head flexed.

Exert gentle outward traction on the baby while rotating the baby first clockwise and then counterclockwise a few degrees to free up the arms.

If the arms are trapped in the birth canal, you may need to reach up along the side of the baby and sweep them, one at a time, across the chest and out of the vagina. (More on this later.)

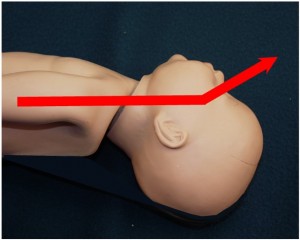

Keep the baby’s body at or below the horizontal plane or axis of the birth canal.

If you bring the baby’s body above the horizontal axis, you risk injuring the baby’s spine through hyperextension.

Only when the baby’s nose and mouth are visible at the introitus is it wise to bring the body up. At this point, you can visually see the attitude of the fetal head and avoid hyperextension.

The application of suprapubic pressure by the assistant is important for keeping the head flexed against the chest, expediting delivery, and reducing the risk spinal injury.

At this stage, the baby is still unable to breath and the umbilical cord is likely occluded.

Without rushing, move steadily toward a prompt delivery.

Placing your finger in the baby’s mouth may help you control the delivery of the head.

Try not to let the head “pop” out of the birth canal. A slower, controlled delivery is less traumatic.

Entrapped Head

Sometimes, after delivery of the fetal torso and arms, the head remains trapped, unable to pass through the cervix. This is a problem that must be promptly resolved.

If the cervix is stretchy enough, increased pushing efforts by the mother and suprapubic pressure by an assistant can overcome mild head entrapment and lead to prompt delivery.

If the cervix is not stretchy enough, or there is more than mild degrees of head entrapment, it will be necessary to cut the cervix longitudinally (Dührson’s Incisions) to quickly enlarge the cervical opening before the fetus is compromised. After delivery, you can repair the cervix. The traditional recommendation for these incisions is at about 10 o’clock and 2 o’clock, but anywhere you can get enough exposure will likely work.

Nuchal Arms

Normally during a breech delivery, the fetal arms remain flexed across the chest and deliver with the fetal torso. Arm entrapment (nuchal arms) occurs when the arms become raised up over the fetal head. Not only must the head pass through the cervix, but the added bulk of one or two arms must come with it. If the cervix is stretchy enough, normal delivery may still occur spontaneously.

In other cases, you must:

- Reach up,

- Identify the shoulder blade

- Follow the humerus as far up to the elbow as you

- Flex the arm, sweeping the extended arm down, across the chest and out of the vagina.

If both arms are trapped, then you must perform this maneuver twice, once for each arm. There are dangers in performing this maneuver, of course. You may dislocate the fetal shoulder, or fracture the shoulder, collarbone, or humerus. Try to be gentle in performing this maneuver to avoid injury to the fetus. Remember, though, that failure to resolve this problem will result in fetal death, so it is important to use that degree of force necessary to deliver the fetus. Broken bones will heal.

Military Settings

In far forward military environments, it is good to remember that most breech babies can be safely delivered without any obstetrical intervention. With that principle in mind, be prepared to watch anxiously (and without pulling on anything) while the breech is delivered primarily through the expulsive efforts of the mother. If the breech becomes stuck, it is most likely due to the fetal arms extending over the head. In this case, follow the guidance above and sweep the arms down across the fetal chest. Then, using your hand over the pubic bone, exert suprapubic pressure to keep the fetal head flexed as it is pushed out from the birth canal.