Technique

The patient is examined while reclining, with the abdomen exposed. Particularly late in pregnancy, this may not be a comfortable position for the patient, who can experience symptoms from inferior vena cava compression by the heavy, gravid uterus. Women in this position should be watched carefully for agitation, shortness of breath, dizziness or faintness.

Should any of these symptoms occur, role the patient onto her side and the symptoms will usually disappear within a few seconds. Once she feels better, you can have her role back, or partially back, to continue the scan. Rarely, a patient will need to be evaluated with her abdomen displaced, either manually, or by maternal position.

A full maternal bladder, often required in the past, is rarely needed with currently used ultrasound equipment.

Scanning is usually done in a darkened (but not dark) room, to minimize the reflected glare off the screen.

After applying a sonic coupling agent to the abdomen, most sonographers begin their evaluation with a simple sweep of the transducer up and down the abdomen and side-to-side across the abdomen to get a rough sense of the uterine contents before focusing on specific areas of interest.

Basic Ultrasound Exam

In evaluating the pregnancy with ultrasound, the following observations are usually made:

- Number of fetuses and their position within the uterus.

- Observation of the fetal heartbeat

- Location of the placenta

- Assessment of amniotic fluid volume

- Determination of gestational age, based on various fetal measurements

- screening evaluation of the fetus for gross anatomic abnormalities.

- Evaluation of the maternal pelvis for masses.

Fetal Anatomic Survey

Definitions vary, but one common collection of views for the fetal anatomic survey include:

- Evaluation of cerebral ventricles (enlarged, small or normal) and the posterior fossa (abnormal fluid collections)

- 4-chamber fetal cardiac view and axis evaluation (the cardiac axis is usually about 45 degrees off a line drawn from anterior to posterior, through the fetal sternum to the fetal spine.

- Fetal spine, including a longitudinal view looking for splaying of the spine, and transverse views, to detect abnormal skin bulges or notching.

- Stomach. The stomach should be present within the abdominal cavity. If empty, it will usually fill by the end of the examination.

- Kidneys.

- Urinary bladder

- Umbilical cord insertion into the fetal abdomen.

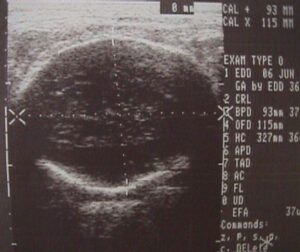

Biparietal Diameter

The biparietal diameter (BPD) is among the most accurate 2nd trimester measures of gestational age. Measured from the beginning of the fetal skull to the inside aspect of the distal fetal skull (“outer to inner”) at the level of the cavum septum pelucidum, this is one of the basic fetal measurements. Using this same image, the frontal occipital diameter (FOD) is obtained and the fetal head circumference (HC) is either obtained directly, or by formula from the BPD and FOD.

The BPD can be used to determine gestational age with a 95% confidence of 10 to 14 days. If the gestational age is already known with precision (1st trimester ultrasound scan), then the BPD can be used to evaluate fetal growth. In cases of symmetrical growth retardation, the fetal BPD will fall below the 10th percentile.

Abdominal Circumference

The abdominal circumference (AC) is a transverse section (coronal) through the fetal abdomen at the level where the umbilical vein enters the liver. The AC may be measured directly, or calculated from the AP and transverse abdominal measurements. Both techniques give good results. Although the AC can be used to calculate gestational age, it is more useful in determining fetal weight. Combined with the BPD, with or without the fetal femur length, reliable formulas can be used to predict fetal weight.

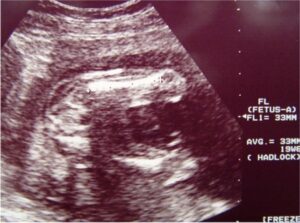

Femur Length

The femur length can be used to determine gestational age, but it is more useful in helping evaluate fetal weight. It is also useful as a marker for fetal malformation and genetic abnormality. Many, though not all, trisomy 21 fetuses will have shortened femurs.

Identify the fetal pelvis. Keeping one end of the transducer over the fetal pelvis, slowly sweep the other end of the transducer in a clockwise fashion toward the fetal small parts. The fetal femur will be found at about a 45 degree angle away from the fetal spine.

Slowly move the transducer back and forth until the longest bright echo within the femur is identified. This is the fetal femur length.

Calculation of Gestational Age

Many fetal measurements can be used to determine gestational age. Early in pregnancy (1st trimester), fetuses of the same gestational age all are nearly identical in size. At this time in pregnancy, there is very little difference in size between those fetuses who ultrimately will be large, average size, or small. As pregnancy continues, these genetic and constitutional differences in size become more important clinically. It is not possible, for example to separate a 20 week fetus who is large from a 21 week fetus of normal size, or a 22 week fetus who is small for its age. All three will measure as though they were 21 weeks.

This divergence of growth rates has two important clinical implications:

The accuracy of ultrasound in predicting gestational age gets worse as the pregnancy advances. By 20 weeks, ultrasound is accurate only to within plus or minus two weeks, and by the third trimester, its accuracy falls to plus or minus 3 weeks.

If, from other sources, you know with certainty the gestational age of the fetus, you can estimate its growth rate by comparing the observed second and third trimester measurements with the expected measurements. Growth rates below the 10th percentile are considered abnormal.

Gestational Age Grid

|

Weeks |

BPD |

FL |

HC |

AC |

|

12 |

21 |

8 |

70 |

56 |

|

13 |

25 |

11 |

84 |

69 |

|

14 |

28 |

15 |

98 |

81 |

|

15 |

32 |

18 |

111 |

93 |

|

16 |

35 |

21 |

124 |

105 |

|

17 |

39 |

24 |

137 |

117 |

|

18 |

42 |

27 |

150 |

129 |

|

19 |

46 |

30 |

162 |

141 |

|

20 |

49 |

33 |

175 |

152 |

|

21 |

52 |

36 |

187 |

164 |

|

22 |

55 |

39 |

198 |

175 |

|

23 |

58 |

42 |

210 |

186 |

|

24 |

61 |

44 |

221 |

197 |

|

25 |

64 |

47 |

232 |

208 |

|

26 |

67 |

49 |

242 |

219 |

|

27 |

69 |

52 |

252 |

229 |

|

28 |

72 |

54 |

262 |

240 |

|

29 |

74 |

56 |

271 |

250 |

|

30 |

77 |

59 |

280 |

260 |

|

31 |

79 |

61 |

288 |

270 |

|

32 |

82 |

63 |

296 |

280 |

|

33 |

84 |

65 |

304 |

290 |

|

34 |

86 |

67 |

311 |

299 |

|

35 |

88 |

68 |

318 |

309 |

|

36 |

90 |

70 |

324 |

318 |

|

37 |

92 |

72 |

330 |

327 |

|

38 |

94 |

73 |

335 |

336 |

|

39 |

95 |

75 |

340 |

345 |

|

40 |

97 |

76 |

344 |

354 |

|

41 |

98 |

78 |

348 |

362 |

|

42 |

100 |

79 |

351 |

371 |

Amniotic Fluid Volume

Amniotic fluid may be increased (polyhydramnios) in the presence of some congenital anomalies, diabetes, and fetal hydrops. It may be reduced (oligohydramnios) in the presence of fetal renal failure, postdate pregnancy, intrauterine growth retardation, and some congenital anomalies.

Amniotic fluid volume (AFV) is often evaluated subjectively by experienced examiners. One rule is that in the presence of polyhydramnios, the fetal shoulders are not both touching the uterine walls at the same time.

Semi-quantitative methods of estimating AFV include the deepest pocket measurement and the amniotic fluid index (AFI). The single deepest pocket of amniotic fluid is measured vertically. If it is at least 2 cm deep, then true oligohydramnios is not considered present. Some sonographers and clinicians find this definition too restrictive and will measure the largest pocket in two diameters.

Using the AFI, the deepest pocket of fluid in each of four uterine quadrants is measured. The four measurements are added to each other. If the sum is less than 7.0 (some say 5.0), then oligohydramnios is present. If more than 25.0, then polyhydramnios is present. While these measurements are commonly used, there is considerable subjectivity involved in obtaining them. Further, the amount of amniotic fluid present varies, depending to some extent on the state of maternal hydration.

Placental Location

In most cases, the exact location of the placenta is of little clinical consequence. In a few cases (such as 2nd and 3rd trimester bleeding, placenta previa, low-lying placenta), the location of the placental is very important.

Level I and Level II Scanning (Screening vs Targeted Scanning)

Level I (screening) scanning consists of the basic evaluation listed above. It is usually relatively simple to perform, readily available, and relatively inexpensive. More detailed scanning (Level II, or targeted scan) requires higher resolution (more expensive) equipment and sonographic skills that are more limited in their availablity and significantly more expensive. Indications for a Level II scan may include:

- Suspicious findings on a Level I scan

- History of prior congenital anomaly

- Insulin dependent diabetes or other medical problem that increases the risk of anomaly.

- History of seizure disorder, particularly if being treated with medications known to increase the risk of anomaly.

- Teratogen exposure

- Elevated MSAFP

- Suspected chromosome abnormality

- Symmetric IUGR

- Fetal arrhythmia

- Oligohydramnios, hydramnios

- Advanced maternal age

Routine Scanning

Debate continues whether all patients should have ultrasound scans, or only those with specific indications. As a practical matter, ultrasound scanning has proven to be so popular with patients and their obstetricians, that almost everyone receiving regular prenatal care ends up with at least one scan anyway. For this reason, the focus of the debate has more recently shifted to when and under what circumstances should patients have ultrasound scans. Those favoring frequent, routine scans, do so on the basis that incorrect gestational age assessments can be corrected, many congenital anomalies can be detected, growth abnormalities can be identified and treated, and multiple gestations identified early, when intervention is more likely to improve results. Those opposed to routine scanning point to the lack of significant improvement in outcome identified to date in large studies or routinely-scanned patients. The debate continues.

Doppler Flow Studies

Using the Doppler principle, blood flow through structures such as the umbilical cord can be identified and quantified. Currently, the best use of this technology has been to identify fetuses with placental vascular resistance, as evidenced by a change (increase) in the systolic/diastolic ratio in the uterine artery. As placental resistance to flow increases, the amount of diastolic flow through the umbilical artery decreases, although systolic flow rates are usually unchanged. As the resistance increases further, diastolic flow into the placenta ceases. In the most severe form of placental resistance, the diastolic flow reverses.

Doppler flow studies can be useful in determining fetal status in the second trimester fetus who is too small for traditional fetal monitoring techniques to be useful. Doppler can also be helpful as another measure of fetal well-being in the potentially compromised fetus with growth restriction.