Electronic fetal monitors continuously record the instantaneous fetal heart rate on the upper channel and uterine contractions on the lower channel.

They do this by attaching, either externally (and non-invasively) or internally, to detect the fetal heart and each uterine contraction.

Labor is an inherently dangerous life event for a fetus and its mother. In the majority of cases, everything goes smoothly enough and ends happily. In a minority of cases, there are some problems. Electronic fetal monitoring is used to provide:

- Minute-by-minute information on the status of the fetus

- Accurate historical information on fetal status and the frequency/duration of contractions from earlier in labor.

- Insight into the stresses on the fetus and its ability to tolerate those stresses.

Originally, electronic fetal monitoring was thought to be able to prevent such newborn problems as stillbirth, brain damage, seizure disorders, and cerebral palsy. This hope proved to be overly optimistic.

Unfortunately, and contrary to earlier thinking, most of the problems that lead to stillbirth, brain damage, seizure disorders and cerebral palsy are not intrapartum problems, but have already occurred by the time a patient comes in to labor and delivery. Nonetheless, electronic fetal monitoring has proved so useful in so many ways that it has become a prominent feature of intrapartum care, and indispensable for high risk patients.

Two forms of continuous electronic fetal heart monitoring are used, internal and external. Internal monitoring provides the most accurate information, but requires a scalp electrode be attached to the fetus, and a pressure-sensing catheter to be inserted inside the uterine cavity. Both of these require membranes be ruptured and both have small, but not inconsequential risks. For that reason, they are usually used only when the clinical circumstances justify the small increased risk of complication.

External monitoring usually provides very good information about the timing of contractions and the fetal response. External monitoring consists of belts worn by the mother during labor that record the abdominal tension (indirectly recording a contraction), and the instantaneous fetal heart rate. External monitoring has the advantages of simplicity, safety, availability, and reasonable reliability under most general obstetrical circumstances. However, it is subject to more artifact than internal monitoring, may not detect subtle changes, and may not accurately record the information, particularly if the mother is overweight or active.

Uterine Blood Flow

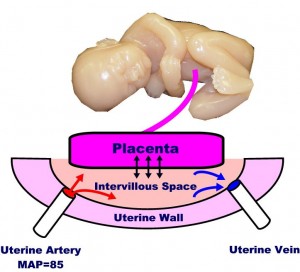

Maternal blood flows to the uterus primarily through the uterine arteries.

The arteries branch out, once they enter the uterus, and supply blood to the muscle cells of the myometrium, and through the wall to the intervillous space (IVS). Once the maternal blood reaches the IVS, it simply dumped into the space, where it drifts about until some is drained off through the maternal venous system. Unlike the highly controlled capillary circulation, there is little control over this process. It is similar to a swimming pool (the IVS), where fresh water is dumped in through a faucet (the maternal arterioles), while the drains in the bottom of the pool (maternal venous system) sucks up any available water that happens to be nearby.

The placenta floats on top of the IVS, with its chorionic villi dipping down into the pool. Across the villous membrane pass oxygen, carbon dioxide, nutrients and waste products. Some of this passage is active transport (eg, glucose), some facilitated (eg, because of pH gradient), and some is passive.

Many factors influence uterine blood flow delivery to the IVS, including:

- Maternal position (lateral, recumbant improves flow)

- Maternal exercise (decreases flow)

- Surface area of the placenta (placental abruption decreases flow)

- Hypotension or hypertension (both decrease flow)

- Uterine contractions (contractions reduce flow)

Once the maternal blood reaches the IVS, oxygen and nutrients must still must traverse the villous membrane. If thickened (as with edema or infection), then transvillous transport of materials will be impaired, at least to some degree.

Effect of Contractions

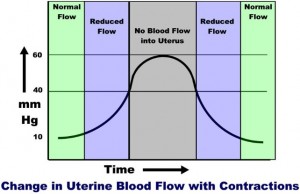

During a uterine contraction, blood flow through the uterus slows. If the contraction is strong enough, all blood flow through it will stop.

This decreased flow occurs because of the pressure gradients in the system.

Maternal mean arterial pressure (MAP) is around 85 mm Hg. The pressure on the inside of the uterus (at rest) is around 10 mm Hg. The pressure within the uterine muscle (intramyometrial pressure or IMP) is usually about 2-3 times that of the intra-amniotic pressure.

Because of these pressures, blood flows from the high pressure uterine arteries, through the intramyometrial spiral arteries (and past the medium pressure intramyometrial zone) and into the low pressure intravillous space. From the IVS, blood is drained out through the even lower pressure venous system and returned to the mother’s circulation.

During a contraction, the intramyometrial pressures rise with the increased muscle tone. As the compressive pressure rises, blood flow through the spiral arteries diminishes (less pressure gradient to drive the blood through them), and then stops when the IMP equals the MAP. The IMP usually equals the MAP when the amniotic fluid pressure is around 40 mm Hg. (Remember that the intramyometrial pressure is 2-3 time that of the amniotic fluid pressure). As the contraction eases up, blood flow through the spiral arteries resumes and by the end of the contraction, blood flow is back to normal.

Thus, with each contraction of any significance, there is initially reduced blood flow to the intervillous space, then a cessastion of blood flow, followed by a gradual resumption of blood flow.

On one level, you could imagine the danger of the fetal oxygen supply being interrupted by each uterine contraction. On another level is the realization that for a normal fetus, this interruption is nearly trivial (similar to holding your breath for 5 seconds). But if the contractions are coming too frequently (with very little time between contractions for the fetus to resupply), or if the fetus already has a significant problem, then contractions can pose a threat.