Menopause is the physiologic cessation of ovarian function (and menstrual flows) that occurs with advancing age in all women. In North America, the average age of menopause is 51, but there is considerable variation from individual to individual. Some (a few) 55 year olds are still having normal menstrual cycles, while some (a few) 47 year olds have stopped.

Many people view menopause as a distinct point in time, beyond which all ovarian function ceases. That might be true for a few women, but for most, menopause is a more gradual process, characterized by waxing and waning ovarian function over a period of many years.

During this time, ovarian function may cease altogether for a few months (accompanied by vasomotor symptoms and amenorrhea), only to return (with disappearance of the symptoms and resumption of menstrual flows). This “off again, on again” pattern is not at all unusual and is probably more the rule than the exception. This many-year period of time is frequently called “peri-menopause.”

Physiology of Menopause

Ovarian function consists of:

- Ovulation

- Estrogen production

- Progesterone production

- Androgen (primarily testosterone) production

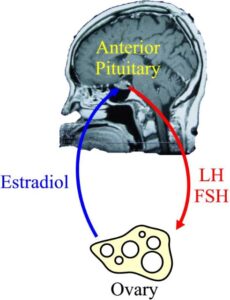

During the reproductive years, the ovaries function under control of the anterior pituitary gland, through its release of follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH). This causes production of estrogen (quite a bit), progesterone (some), testosterone (not much, but very important), and ovulation. Of these functions, ovulation is the most complex, while production of testosterone is the simplest.

The estradiol (estrogen) produced by the ovary circulates through the woman’s bloodstream to receptors in the brain (primarily anterior pituitary), where it inhibits release of FSH. Consequently, the stimulus to the ovary to produce its hormones and release its eggs diminishes, menstruation occurs, and the whole process begins anew.

Menopause occurs because the ovaries stop responding to FSH and LH, not because the brain stops releasing FSH and LH. A menopausal woman will generally have very high levels of FSH and LH, but very low levels of estrogen (estradiol) in her bloodstream.

Symptoms

Common symptoms of menopause include:

- Hot flashes (sudden, unprovoked flushing of the face and trunk, accompanied by redness and profuse sweating, and often followed by chills.

- Night sweats (awakening in the middle of the night drenched in sweat, requiring a change in night clothes).

- Vaginal dryness (particularly noticable during intercourse)

- Diminished memory (forgetfulness)

- Dry skin

- Mood changes, including fatigue, depression and irritability

- Sleeplessness

- Cessation of menstrual flows

- Decreased libido

Medical Issues

Accompanying menopause are two medical problems, bone loss and heart disease.

Women slowly lose bone mass, starting at a relatively early age. Menopause rapidly accelerates this process, resulting in osteopenia (decreased bone density) or osteoporosis (so much bone loss that pathologic fractures are a realistic possibility).

The incidence of heart disease also increases rapidly after menopause. During their reproductive years, women enjoy a substantial advantage over men in heart disease. With menopause, the risk of heart disease among women rises to that of men, with women losing the relative protection that they had earlier.

Osteoporosis

This demineralization problem can be extremely serious. Pathologic fractures are notorious for poor healing. The morbidity and mortality associated with recovery from fractures of the hip, spine and long bones is substantial.

Taking extra calcium (1000-1500 grams of elemental calcium/day) is helpful in preventing osteoporosis, but the help is very small. Similarly, regular weight-bearing exercise is helpful, but only to a limited extent. Taking estrogen helps a great deal, but usually won’t reverse the effects of osteoporosis. Bisphosphonates, such as alendronate are even more powerful and can reverse osteoporosis, although they can cause significant side effects.

Increased risk factors for osteoporosis include:

- Slender build

- Tobacco smoking

- Caucasian

- Sedentary life style

- Chronic glucocorticoid use

- Paget` Disease of the bone

Bone density studies (Dexa Scan) will show a T-value of -2.5 or worse among women with osteoporosis. Osteopenic women have T-values of -1.0 to -2.5.

Philosophy of Menopause

Two basically opposite and conflicting philosophies of menopause complicate the treatment of menopause.

One philosophy holds that:

- Menopause is a natural event, affecting everyone sooner or later.

- The normal status of women after approximately age 50 is to be menopausal, without any estrogen.

- The role of medication, if any, is to ease the transition from pre-menopause to menopause, helping women adjust to not having any estrogen

- Any medical treatment of menopause should involve the smallest amount of the fewest number of medications, for the shortest period of time possible. Then, the medications should be steadily withdrawn so that the menopausal woman will not become dependent upon it.

The other philosophy holds that:

- Menopause is an estrogen-deficiency state.

- Womanhood is more or less defined by the effects of estrogen, which assists in the development not only of the breasts and genitals, but the skin, body fat, voice, memory, verbal skills, and to some extent the charitable disposition, sociability, and nurturing personalities that are so characteristic of women across geographic and racial boundaries.

- Estrogen deprivation creates problems that are not only medical, but frequently annoying, psychologically distressing, and largely corrected through the use of estrogen replacement therapy.

- The fact that everyone is affected by menopause sooner or later should not deter us from treating it, any more than the commonality of arthritis or age-related dementia would deter us from treating them.

- We should treat estrogen-deficient women with estrogen to restore them to their normal status, just as we would treat hypothyroid patients with thyroid medication to make them euthyroid, or give diabetic patients insulin…enough to restore them to their normal situation.

- Menopause is not a universal experience in the animal kingdom…it is seen only among humans.

Given these two differing philosophies, it is not difficult to imagine that there are disagreements among conscientious practitioners as to the proper role of estrogen replacement therapy.

Menopause is a relatively new issue in the human experience. Until recently, very few women lived long enough to reach menopause. The average life expectancy for women in North America in 1900 was age 42. Currently it is age 82. Because of this, our clinical experience with large numbers of menopausal patients is really limited to the last century. As physicians, I expect we will learn a great deal more about menopause in the coming century, when the philosophical differences may be resolved.

Benefits and Risks of Estrogen Replacement Therapy

There is conflicting evidence in research studies about the relative benefits and risks of estrogen replacement therapy. That said, it is probably true that estrogen replacement of the proper dose will:

- Eliminate hot flashes and night sweats

- Provide moderate protection of the bones against demineralization

- Improve or eliminate vaginal dryness

- Improve sleep

- Improve memory

- Provide for an improved general sense of well-being for many menopausal women.

It is also probably true that estrogen replacement therapy:

- Will not protect against cardiovascular disease and may increase that risk slightly

- Will increase the risk of gall bladder disease.

- Will not affect the overall risk of developing cancer.

- For those who develop cancer while taking estrogen replacement, will increase the chance that the cancer will originate in the breast, but decrease the risk of it arising in the colon or uterus.

- Will not affect the overall risk of death

- Will increase the risk of certain types of strokes, while decreasing the risk of other types of strokes, with an overall slight increase in risk of stroke from all types.

Breast Cancer

There is conflicting evidence over the role of estrogen in causing breast cancer, causing its recurrence, or speeding its growth and development. Some physicians feel that any woman with a past history of breast cancer should never take estrogen. Others feel that for some women, the risks are modest (particularly if the breast cancer was many years ago), and the benefits in terms of quality of life are considerable, and willingly prescribe estrogen to these patients.

Progesterone

Taken alone, estrogen replacement in standard doses is associated with an increased risk of uterine cancer. The addition of progesterone to the estrogen not only blocks the increased risk of uterine cancer, it reduces the risk to less than that of women who don’t take any ERT at all. For this reason, progesterone has routinely been added to estrogen replacement regimens for women who have uteruses. Women who have undergone hysterectomy have no need for the progesterone addition.

Progesterone blunts, to some extent, some of the other estrogenic effects, and the best of the long term studies have not reported their results from estrogen-alone therapies. It is possible that some of the risks of ERT are actually a result of the progesterone.

Testosterone

Male hormone, primarily testosterone, is produced in small amounts by women, with about one-third coming from the ovaries. As ovarian function gradually slows down, testosterone production stops, usually a few years after the onset of amenorrhea. At that time, serum testosterone levels will fall by about 30%.

For many women, this 30% drop in testosterone will be unnoticed. For others, they may experience symptoms of low testosterone, the most prominent of which are lethargy and decreased sex drive.

For women with complaints of lethargy and decreased libido during menopause, some physicians will routinely measure serum testosterone. If testosterone levels are relatively low, these women may benefit from a therapeutic trial of small doses of testosterone, usually in addition to estrogen replacement. Serum testosterone levels are followed to make sure that the woman is not receiving too much hormone. Many women find this combination neatly resolves their symptoms.

Not everyone benefits from this regimen. Some have side-effects (hair growth, voice changes, adverse lipid changes), that require stopping the testosterone. Others notice no difference in their energy levels or libido.

Estrogen Replacement Regimens

A number of satisfactory treatment strategies and doses are available for estrogen replacement therapy. They include both continuous and cyclic approaches. The benefits to continuous therapy are simplicity and absence of menstrual bleeding in the majority of women. For a minority, spotting or breakthrough bleeding complicate continuous therapy and these women generally do better on a cyclic approach. For those on cyclic therapy, 1/3 experience normal menstrual flows, 1/3 have no periods at all, and 1/3 will initially experience menstrual flows, but the flows will gradually abate over time. The following are examples of typical ERT doses:

| Continuous therapy: | Cyclic therapy: |

| Conjugated estrogens* 0.625 mg PO daily, plus medroxyprogesterone acetate** 2.5 mg PO daily | Conjugated estrogens* 0.625 mg PO daily, plus medroxyprogesterone acetate** 5 mg PO, the 1st through the 10th of each month |

| *May substitue estradiol 1.0 mg **May substitute micronized progesterone 100 mg |

Once the patient is started on the estrogen replacement, it is important to see how she’s doing in 1-3 months after starting it. If she continues to have vasomotor symptoms, then she needs a higher dose of estrogen. If she has persistent breast tenderness or headaches, she may be getting too much estrogen. Measuring serum estrogen (estradiol) levels may prove helpful in managing such women.

Serum Estradiol

Blood estrogen levels may be useful in the management of many menopausal women and their estrogen replacement therapy.

During the reproductive years, estrogen levels vary with the menstrual cycle:

|

Serum Estradiol Levels |

|

| Proliferative Phase | 60-250 pg/ml |

| Luteal Phase | 75-450 pg/ml |

| Menopause | <10 pg/ml |

| ERT | 50-100 pg/ml |

In menopause, the estradiol levels typically are less than 32 pg/ml and often <10. When treating menopausal women with estrogen, a reasonable target would be estradiol levels of 50-100 pg/ml. If the patient has levels a little higher or lower, but feels fine, then she can remain on the same dose. However, a woman on standard doses of estrogen who continues to have vasomotor symptoms and whose estradiol level is only 40 will likely benefit from a higher dose, nudging her into the typical therapeutic range.

Abnormal Bleeding

The progesterone component of estrogen replacement therapy provides some protection against endometrial hyperplasia and carcinoma, but the protection is not absolute. For that reason, women taking estrogen replacement therapy who experience abnormal bleeding (any bleeding that is not expected) should be carefully evaluated. Usually, nothing significant is found.

Resumption of ovarian function

It is relatively common for women who are started on estrogen replacement therapy to resume some degree of ovarian function. Giving estrogen will inhibit the release of FSH and LH and serum levels of these gonadotropins will fall. Then, in response to stopping the estrogen (as in some forms of cyclic therapy), the FSH will again rise. The ovaries, particularly if they are still relatively close to the time of menopause may respond briefly to the rising level of FSH, even though they didn’t respond to the sustained high levels of FSH.

Such an occurrence can lead to brief resumption of estrogen production (and resultant estrogen excess symptoms of breast tenderness or bleeding), or even ovulation (resulting in a full-blown menstrual period two weeks later). Pregnancy occurring in this circumstance would be very unlikely because the the quality of the older ovarian follicle is usually poor. The main problem is an unexpected menstrual flow occurring in a woman who was advised she was menopausal and who is now receiving treatment for menopause. An advance explanation of this possibility will relieve the patient’s anxiety and concern over the depth of your knowledge and skill.

At least two approaches to this problem can be effective:

One approach is to stop estrogen replacement and allow the woman’s natural cycle to continue for as long as it wants. Eventually, she will again become amenorrheic and experience vasomotor symptoms and conventional ERT can be resumed.

A second approach is to switch from conventional ERT to oral contraceptive pills. The pills have enough estrogen in them to provide reasonable coverage for most women, and the progestin is strong enough to suppress further ovarian function. After taking the OCPs for a reasonable time (6-12 months), she can be switched back to conventional ERT.