Bleeding during the third trimester has special clinical significance, encompassing problems that are quite serious and those that are normal or expected.

It is important to be able to distinguish between them.

Bloody Show

As the cervix thins (effaces) and begins to dilate in preparation for labor, the patient may notice the passage of some bloody mucous.

This is a normal event during the days leading up to the onset of labor at term. If this is the only symptom, the patient can be reassured of its normalcy. If the patient is also having significant contractions, she should be evaluated for the possible onset of labor.

If this bloody mucous show appears prior to full term, then it may signal the imminent onset of preterm labor. These patients are evaluated for possible pre-term labor.

Bleeding that is more than bloody mucous (bright red, no mucous, passage of clots) requires further evaluation.

Cervicitis and Cervical Trauma

During pregnancy, the cervix becomes softer, more fragile, and more vulnerable to the effects of trauma and microbes.

Cervical ectropion, in which the soft, mucous-producing endocervical mucosa grows out onto the exocervix is common among pregnant women. This friable endocervical epithelium bleeds easily when touched. This situation can lead to spotting after intercourse, a vaginal examination, or placement of a vaginal speculum.

Cervical ectropion also can lead to cervicitis. The normal squamous cell cervical epithelium is relatively resistant to bacterial attack. The endocervical mucosa is less resistant. If infected, the cervical ectropion is even more likely to bleed if touched.

These changes are usually easily seen during a vaginal speculum exam.

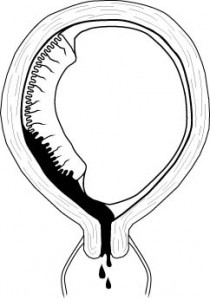

Placental Abruption

Placental abruption is also known as a premature separation of the placenta.

All placentas normally detach from the uterus shortly after delivery of the baby. If any portion of the placenta detaches prior to birth of the baby, this is called a placental abruption. Placental abruption occurs in about 1% of all pregnancies.

Classically, placental abruptions present with vaginal bleeding and frequent, painful uterine contractions. Occasionally, either or both of these may be absent.

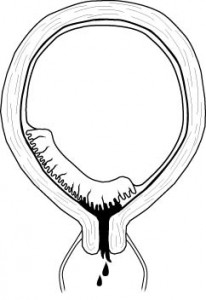

Placenta Previa

Normally, the placenta is attached to the uterus in an area remote from the cervix.

Sometimes, the placenta is located in such a way that it covers the cervix. This is called a placenta previa.

A placenta previa is inherently unstable, as whenever the cervix moves or dilates, it creates the opportunity for significant vaginal bleeding. This bleeding may range from minor to catastrophic.

Because a pelvic exam may provoke further bleeding it is important to avoid a vaginal or rectal examination in pregnant women during the second half of their pregnancy unless you are certain there is no placenta previa.

Clinical approach to third trimester bleeding

The clinical approach depends on the clinical situation. For example:

A 3rd trimester patient who is hemorrhaging (500 cc with continuing active bleed) bright red blood should go directly to the operating room for a cesarean section to deliver her from the placental abruption or placenta previa. While en route to the OR, call for blood transfusions and lab tests to identify any coagulopathy.

A patient at term with regular contractions and a small amount of bloody mucous can be examined vaginally after confirming (through ultrasound or clinical exam of the abdomen) that there is no placenta previa.

Patients with bright red vaginal bleeding that is less than hemorrhage should be carefully evaluated prior to performing a pelvic exam. Ultrasound can be helpful in locating the placenta and looking for retroplacental blood clot.

Laboratory tests for coagulopathy can be helpful. Hgb is useful, not to determine whether to transfuse or not (that is a clinical, not laboratory decision), but to indicate the margin of safety available to the clinician in caring for this patient. Continuous electronic fetal monitoring is important to determine the degree of tolerance the fetus has for this bleeding and the extent to which uteroplacental circulation has been disrupted. After ruling out a placenta previa, examine the patient with a speculum to determine the source of the bleeding (from the cervical os? from the surface of the cervix? from a laceration of the vaginal wall? etc.)

Clinical Management of Hemorrhagic Shock

Shock is the generalized inadequate perfusion of the tissues of the body.

The cause of shock may be low cardiac output (cardiogenic shock), low blood volume (hypovolemic shock), or other other etiologies (septic shock, toxic shock).

The greater the blood loss, the worse the clinical problem and the more dramatic the clinical findings.

More information on the Clinical Management of Hemorrhagic Shock

Blood Transfusion

The ideal material for use in hemorrhagic shock would be disease-free, body-temperature, fresh, whole blood, with identical blood type and major and minor blood groups.

This has excellent oxygen-carrying capacity, platelets, coagulation factors, volume and colloid, and would be totally non-reactive within the victim’s bloodstream. Unfortunately, this ideal material does not exist (at least not when quickly needed), so we usually compromise, using various blood products, depending on the needs of the patient.

In an extreme emergency, you can give the patient type O negative packed RBCs from the blood bank. For someone whose blood type is unknown and there is no time for cross-matching, this is the best approach. If type O negative blood is not available, type O positive can be substituted with good results, but there is a fair chance that the patient (if Rh negative) will become sensitized against the Rh factor. Still, that may be preferable to losing the patient because they weren’t transfused quickly enough. If the patient’s blood type is known, you can give type specific blood to her. If she is type B positive, you can give type B positive blood to her. In either case, it is best to draw a plain tube of blood just before giving the non-crossmatched blood to help in figuring out her native blood type.

If you have more time, it is better to give cross-matched blood. Cross-matched means the type (A, B, AB, or O) will match, and the major factors (Rh, Kell, etc.) will match. There will undoubtedly be some minor factors that do not match, and the degree of a match hinges, in part, on the size of your blood bank and the available time.