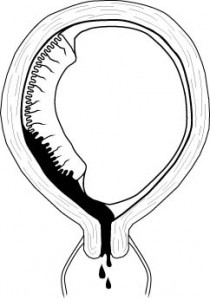

Placental abruption is also known as a premature separation of the placenta.

All placentas normally detach from the uterus shortly after delivery of the baby. If any portion of the placenta detaches prior to birth of the baby, this is called a placental abruption. Placental abruption occurs in about 1% of all pregnancies.

A placental abruption may be partial or complete.

A complete abruption is a disastrous event. The fetus will die within 15-20 minutes. The mother will die soon afterward, from either blood loss or the coagulation disorder which often occurs. Women with complete placental abruptions are generally desperately ill with severe abdominal pain, shock, hemorrhage, a rigid and unrelaxing uterus.

Partial placental abruptions may range from insignificant to the striking abnormalities seen in complete abruptions.

Clinically, an abruption presents after 20 weeks gestation with abdominal cramping, uterine tenderness, contractions, and usually some vaginal bleeding. Occasionally, the blood loss is trapped inside the uterus. These cases are called “concealed abruptions.”

A number of factors are associated with an increased risk of placental abruption, among them:

- Prior placental abruption (roughly doubles the risk of abruption in a subsequent pregnancy)

- Abdominal trauma, including motor vehicle accidents

- High maternal parity

- Low socio-economic status

- Poor nutrition

- Use of cocaine or its derivatives

- Maternal hypertension, including pre-eclampsia and eclampsia

- Polyhydramnios

- Oligohydramnios

- Cigarette smoking

- Multiple gestation

Abruptions are often diagnosed clinically, based on the symptoms of bright red vaginal bleeding, frequent contractions and uterine tenderness. There are no laboratory findings that are specific for placental abruption. In mild cases, laboratory tests are usually normal. In more advanced cases, the Hgb and Hct go down, as do the platelets and fibrinogen (due to the massive bleeding and consumption of coagulation factors) while fibrin split products go up. Large numbers of fetal RBCs may be identified in the maternal blood.

In the case of large abruptions, ultrasound may identify a retroplacental blood clot. In milder cases, ultrasound scans are frequently normal.

Mild abruptions may resolve with bedrest and observation, but the moderate to severe abruptions generally result in rapid labor and delivery of the baby. If fetal distress is present (and it sometimes is), rapid cesarean section may be needed.

Because so many coagulation factors are consumed with the internal hemorrhage, coagulopathy is common. This means that even after delivery, the patient may continue to bleed because she can no longer effectively clot. In a hospital setting, this can be treated with infusions of platelets, fresh frozen plasma and cryoprecipitate. If these products are unavailable, fresh whole blood transfusion will give good results.