a. The integumentary system consists of the skin and its derivatives.

This is the largest and one of the most complex systems of the body. The surface area of the skin covers about 1.8 square meters (16.2 square feet) of the body of the average male adult. The skin weighs about six pounds and receives roughly one-third of all blood circulating through the body.

It is difficult to think of the skin as a system, but it is a complex of organs (sweat glands, oil glands, and so forth). The skin is elastic, regenerates, and functions in protection, thermoregulation, and sensation.

b. The protection, sensations, secretions, and the other functions which the integument gives to the rest of the body are essential for life. Changes in the normal appearance of the skin often indicate abnormalities or disease of body function.

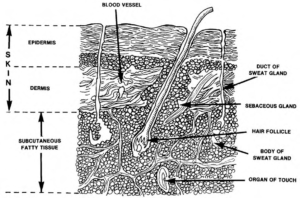

c. Skin consists of three distinct layers: the epidermis, the dermis, and the subcutaneous layers (see figure 2-1).

The top layer, the epidermis, is attached to the second layer, the dermis. The dermis is thick, connective tissue.

The subcutaneous layer, the third layer of skin, is located beneath the dermis and consists of areolar (minute spaces in tissue) and adipose (fat) tissues. The first skin layer is fixed to the second skin layer as though the two were glued together. The second and third skin layers are attached in a different way. Fibers from the second layer (the dermis) extend down into the third layer (subcutaneous), anchoring the two layers together. The third layer is firmly attached to underlying deep fasciae.

(1) Epidermis. The epidermis is composed of stratified, squamous (scalelike), epithelial cells which are organized in four or five layers.

The number of cell layers depends on the location of the skin on the body. The epidermis has five layers on the palms of the hands and the soles of the feet because these areas have more wear and tear. Skin on other parts of the body has four layers of epidermis because there is less exposure to frictions. The layers of the epidermis from the deepest to the most superficial are described below.

(a) Stratum basale. Cells continually multiply and push upward toward the surface.

(b) Stratum spinosum. Eight to ten rows of polyhedral (many-sided) cells which fit closely together make up this layer of epidermis. New cells germinate in this layer.

(c) Stratum granulosum. Three to five rows of flattened cells containing keratohyalin, a substance which will finally become keratin, make up this layer of epidermis. The nuclei of cells are in various stages of degeneration-breaking down and dying.

(d) Stratum lucidum. This layer is thicker on the palms of the hands and the soles of the feet. The layer consists of several rows of clear, flat, dead cells which contain droplets of a clear substance called eleidin. Eleidin eventually becomes keratin.

(e) Stratum corneum. Twenty-five to thirty rows of flat, dead cells which are completely filled with keratin make up this layer. These cells are shed and replaced continuously so that roughly every twenty-eight days, this layer is new. It is this layer with its water-proofing protein keratin that protects the body against heat and light waves, water, bacteria, and many chemicals.

(2) Dermis.

(a) Characteristics. The second layer of skin, the dermis or corium, is sometimes called the true skin. This layer holds the epidermis in place by connective tissue and elastic fiber. The dermis is very thick on the palms of the hands and the soles of the feet but very thin on the eyelids, penis, and scrotum. The dermis contains the following: numerous blood vessels, nerves, lymph vessels, hair follicles, sweat glands, and sensory receptors.

(b) Papillary layer. This upper one-fifth of the dermis has small, fingerlike projections called dermal papillae. These projections reach into the concavities between ridges in the deep surface of the epidermis. This region or layer consists of loose connective tissue containing fine, elastic fibers.

(c) Reticular layer. This layer makes up the rest of the dermis. The reticular layer consists of dense, irregularly arranged connective tissue that has interlacing bundles of collagenous and coarse fibers. Between the fibers are adipose (fat) tissue, hair follicles, nerves, oil glands, and the ducts of sweat glands.

The collagenous and elastic fibers together give the skin strength, extensibility, and elasticity. The skin stretches during pregnancy, obesity, or edema. Elasticity allows the skin to contract after such stretching. If the skin has been stretched severely, small tears may occur. Initially, the tears are red; they lose the redness but remain visible as silvery white streaks called striae.

NOTE: Extensibility is the ability to stretch. Elasticity is the ability to return to original shape after extension or contraction.

(3) Subcutaneous-adipose. This layer is composed of loose connective tissue combined with adipose (fatty) tissue. The subcutaneous layer of skin has several important functions. The primary functions are listed below.

(a) Storehouse for water and particularly for fat. Much of the fat in an overweight person is in this layer.

(b) Layer of insulation protecting the body from heat loss.

(c) Pads the body giving the body form and shape and cushioning and protecting the body from blows.

(d) Provides a pathway for nerves and blood vessels.