LESSON OBJECTIVES

8-1. Select from a list of facts, those facts related to the surgical experience.

8-2. Identify items found on DD Form 1924, Surgical Check List.

8-3. Identify nursing implications related to preoperative preparation of a patient.

8-4. Select from a list, the definition of perioperative patient care.

8-5. Select from descriptive statements, the key members of the surgical team.

8-6. Identify nine factors, which effect selection of an anesthetic agent.

8-7. Identify three factors the anesthesiologist/anesthetist considers when selecting an anesthetic agent.

8-8. Identify three major classifications of anesthetic agents.

8-9. Select from a list, the descriptor for the purpose of surgical intervention.

8-10. Select from a list, complications which should be prevented in the recovery room.

8-11. Select from a list of facts, those facts related to respiratory distress.

8-12. Identify nursing implications related to the prevention of respiratory distress.

8-13. Select from a list of facts, those facts related to hypovolemic shock.

8-14. Identify nursing implications related to the detection of pending hypovolemic shock.

8-15. Identify nursing implications related to the general care of a patient in the recovery room.

8-16. Select from a list, the effects of anesthesia during the postoperative period

8-17. Select from a list, possible negative effects of surgery on the integumentary system.

8-18. Match the type of postoperative wound closure and the appropriate healing processes.

8-19. Select from a list of factors, those factors that may impair wound healing.

8-20. Given a description of wound drains, select the type of wound drain described.

8-21. Identify nursing implications related to the care of a postoperative patient according to body systems or related to the care of a postoperative patient in general.

8-1. INTRODUCTION

a. Perioperative refers to the total span of surgical intervention. Surgical intervention is a common treatment for injury, disease, or disorder. The surgeon intervenes in the disease process by repairing, removing, or replacing body tissues or organs. Surgery is invasive because an incision is made into the body or a part of the body is removed.

b. Perioperative patient care is a variety of nursing activities carried out before, during, and after surgery. The perioperative period has three phases:

(1) The preoperative phase begins with the decision that surgical intervention is necessary and ends when the patient is transferred to the operating room table.

(2) The intraoperative phase is the period during which the patient is undergoing surgery in the operating room. It ends when the patient is transferred to the post-anesthesia recovery room.

(3) The postoperative phase lasts from the patient’s admission to the recovery room through the complete recovery from surgery.

8-2. THE SURGICAL EXPERIENCE

a. Surgery is classified as major or minor based on the degree of risk for the patient. Surgery may be classified as elective, meaning that it is necessary but scheduled at the convenience of the patient and the health care provider. When surgery must be done immediately to save the patient’s life, a body part, or bodily function, it is classified as emergency surgery. Regardless of whether the surgery is major or minor, elective or emergency, it requires both physical and psychosocial adaptation for the patient and his family. It is an important event in a person’s life.

(1) Minor surgery is brief, carries a low risk, and results in few complications. It may be performed in an outpatient clinic, same-day surgery setting, or in the operating suite of a hospital.

(2) Major surgery requires hospitalization, is usually prolonged, carries a higher degree of risk, involves major body organs or life-threatening situations, and has the potential of postoperative complications.

b. Surgery produces physical stress relative to the extent of the surgery and the injury to the tissue involved. Surgical intervention may be for one or more reasons. The following descriptors classify surgical procedures by purpose:

(1) Ablative–removal of a diseased organ or structure (e.g., appendectomy).

(2) Diagnostic–removal and examination of tissue (e.g., biopsy).

(3) Constructive–repair a congenitally malformed organ or tissue. (e.g., harelip; cleft palate repair).

(4) Reconstructive–repair or restoration of an organ or structure (e.g., colostomy; rhinoplasty, cosmetic improvement).

(5) Palliative–relief of pain (for example, rhizotomy–interruption of the nerve root between the ganglion and the spinal cord).

(6) Transplant–transfer an organ or tissue from one body part to another, or from one person to another, to replace a diseased structure, to restore function, or to change appearance (for example, kidney, heart transplant; skin graft).

c. The physical stress of surgery is greatly magnified by the psychological stress. Anxiety and worry use up energy that is needed for healing of tissue during the postoperative period. One or more of the following may cause the patient psychological stress.

(1) Loss of a body part.

(2) Unconsciousness and not knowing or being able to control what is happening.

(3) Pain.

(4) Fear of death.

(5) Separation from family and friends.

(6) The effects of surgery on his lifestyle at home and at work.

(7) Exposure of his body to strangers.

d. Surgical procedures usually combine several classifications and descriptors. For example, a trauma patient may require major, reconstructive, emergency surgery. Regardless of the risk, any surgery that imposes physical and psychological stress is rarely considered “minor” by the patient.

8-3. NURSING IMPLICATIONS

a. Patients are admitted to the health care facility for surgical intervention from a variety of situations and in various physical conditions. The nurse is responsible for completion of preoperative forms, implementing doctor’s orders for preoperative care, and documentation of all nursing measures.

b. The following nursing implications are related to preparing a patient for surgery.

(1) Prepare the patient’s chart using DD Form 1924, Surgical Check List (figure 8-1). DD Form 1924 contains the following information:

(a) Space for the patient’s identification.

(b) A checklist for pertinent clinical records.

(c) A space for recording the most current set of vital signs taken prior to preoperative medications.

(d) A space to indicate allergies.

(e) A space to document all preoperative nursing measures.

(f) A space to document any comment that indicates something very special about this particular patient (for example, removal of prosthesis, patient hard of hearing).

(g) A space for signature of release by the registered nurse when all actions are completed.

(2) Ensure completion of SF 522, Request for Administration of Anesthesia and for Performance of Operations and Other Procedures (figure 8-2).

(a) SF 522 is a legal document, which satisfies requirement of informed consent. A surgical consent form must be signed by the patient before surgery can be performed.

(b) It must be signed by the physician and anesthesiologist to indicate that all risks of surgery and anesthesia have been fully explained to the patient.

(c) The patient must sign in the presence of a witness, to consent for the surgical procedure. The witness is attesting to the patient’s signature, not to the patient’s understanding of the surgical risks. If the adult patient is unconscious, semiconscious, or is not mentally competent, the consent form may be signed by a family member or legal guardian.

(d) If the patient is a minor (usually under the age of 18), the consent form is signed by a parent or legal guardian. A minor who lives away from home and is self-supporting is considered emancipated and he may sign.

(e) Legal age is established on a state-by-state basis. Be familiar with the age of consent for the state in which the health care facility is located and with legal implications when a person other than the patient signs the consent form.

(f) Legal consent forms must be signed prior to administration of preoperative medication or any type of mind-altering medication or the document is not legally binding.

(g) SF 522 must be timed and dated.

(3) Implement doctor’s orders for preoperative care.

(a) If ordered, administer an enema. The enema cleanses the colon of fecal material, which reduces the possibility of wound contamination during surgery.

(b) If ordered, assure that the operative site skin prep (shave) is done. An operating room technician or other designated person will clean and shave a wide area surrounding the planned site for the incision. (This may be done in the operating room immediately before surgery). The skin prep frees the skin of hair and microorganisms as much as possible, thus decreasing the possibility of them entering the wound via the skin surface during surgery.

(c) The doctor will give specific directions concerning withholding food and fluid before surgery. Assure that the order is followed. Typically, the patient may eat solid food until supper, but can have nothing by mouth (NPO) beginning at midnight before surgery. Place the NPO sign outside the patient’s room. Instruct the patient of the importance and the reason for being NPO. Remove the water pitcher and the drinking glass. Clearly mark the diet roster.

(d) If ordered, administer a sedative. The evening before surgery a hypnotic drug, such as flurazepam hydrochloride (Dalmane®) may be given so that the patient can get a good night’s sleep.

8-4. PREPARING THE PATIENT FOR SURGERY

a. Preoperative preparation may extend over a period of several days. The patient may undergo tests, radiographic studies, and laboratory procedures. A medical history is taken and a physical examination performed before surgery. Patients scheduled for elective surgery may have laboratory tests such as urinalysis, complete blood count, hemoglobin, and hematocrit done as an outpatient. The nurse plays an important role in explaining the necessity for preoperative tests and in carrying out preparations for these tests. The immediate preparation for surgery usually starts the evening before surgery. Nursing implications related to the preoperative preparation of a patient are:

(1) Assist the patient with personal hygiene and related preoperative care.

(a) The evening before surgery, the patient should take a bath or shower, and shampoo hair to remove excess body dirt and oils. The warm water will also help to relax the patient. Sometimes plain soap and water are used for cleansing the skin, but a topical antiseptic may be used.

(b) Remove all makeup and nail polish. Numerous areas (face, lips, oral mucosa, and nail beds) must be observed for evidence of cyanosis. Makeup and nail polish hide true coloration.

(c) Jewelry and other valuables should be removed for safe keeping. The patient may wear a wedding band to surgery, but it must be secured with tape and gauze wrapping. Do not wrap tightly; circulation may be impaired. Do not leave valuables in the bedside stand or store in the narcotics container. If possible, send these items home with a relative until the patient has need of them. Chart what has been done with the valuables.

(2) Provide information concerning surgery.

(a) The patient is told about the risks and benefits of surgery, the likely outcome if surgery is not performed, and alternative methods of treatment by his doctor. However, the nurse can help the patient cope with the upcoming surgery by taking the time to listen to the patient and others who are concerned about his well being, and answering other questions.

(b) Explain each preoperative nursing measure.

(c) Provide an opportunity for the patient to express his feelings. Ask about spiritual needs and whether he wishes to see a Chaplain.

(d) Provide family members with information concerning their role the morning of the surgery. Give them the surgical waiting room location, and the probable time that they can visit the patient after surgery. Explain the rationale for the patient’s stay in the recovery room. Inform them of any machines or tubes that may be attached to the patient following surgery.

(3) Provide preoperative morning care.

(a) Awake the patient early enough to complete morning care. Give him a clean hospital gown and the necessary toiletries. The patient should have another shower or bath using a topical antiseptic, such as povidone-iodine. The skin cannot be made completely sterile, but the number of microorganisms on it can be substantially reduced. If the surgery is extensive, it may be several days before the patient has another shower or “real” bath.

(b) The patient should have complete mouth care before surgery. A clean mouth provides comfort for the patient and prevents aspiration of small food particles that may be left in the mouth. Instruct the patient not to chew gum.

(4) Remove prostheses. Assist the patient or provide privacy so that the patient can remove any prostheses. These includes artificial limbs, artificial eyes, contact lenses, eyeglasses, dentures, or other removable oral appliances. Place small items in a container and label them with the patient’s name and room number. Dentures are usually left at the bedside.

(5) Record vital signs. Obtain and record the patient’s temperature, pulse, respiration, and blood pressure before the preoperative medication is administered.

b. Allow the patient time to complete any last minute personal measures and visit with the family.

c. Recheck the accuracy of DD Form 1924, Surgical Check List.

d. If ordered, administer preoperative medications. Pre-op medications are usually ordered by the anesthesiologist, and administered about 30 to 60 minutes before the patient is taken to the operating room.

(1) The medications may be ordered given at a scheduled time or on call (the operating room will call and tell you when to give the medications).

(2) The medications may consist of one, two, or three drugs: a narcotic or sedative; a drug to decrease secretions in the mouth, nose, throat, and bronchi; and an antiemetic.

(3) Have the patient void before administering the medications.

(4) Explain to the patient the effects experienced following administration of the medications (drowsiness, extreme dry mouth).

(5) Instruct the patient to remain in bed. Raise the side rails on the bed and place the call bell within easy reach.

e. Assist the operating room technician. The patient is usually transported to the operating room on a wheeled litter, or gurney. The technician should cover the patient with a clean sheet or cotton blanket. Assist the technician to position the patient on the litter. See that the patient is comfortable, and that the restraint is fastened to prevent him from falling off the litter.

8-5. DOCUMENT NURSING MEASURES

a. All necessary information should be recorded on the chart before the patient leaves the nursing unit. Check the patient’s identification band to be sure the right patient is being taken to surgery. Check the consent form to be sure that it is correctly signed and witnessed.

b. “Sign out” the patient in the nurse’s notes. Include the date, the time, the event, and your observations on the status of the patient. “Sign off” DD Form 1924, Surgical Check List.

SECTION II. THE INTRAOPERATIVE PHASE

8-6. THE SURGICAL TEAM

a. Key Members. The intraoperative phase begins when the patient is received in the surgical area and lasts until the patient is transferred to the recovery area. Although the surgeon has the most important role in this phase, there are five key members of the surgical team.

b. The Surgeon. The surgeon is the leader of the surgical team. The surgeon is ultimately responsible for performing the surgery effectively and safely; however, he is dependent upon other members of the team for the patient’s emotional well being and physiologic monitoring.

c. Anesthesiologist/Anesthetist. An anesthesiologist is a physician trained in the administration of anesthetics. An anesthetist is a registered professional nurse trained to administer anesthetics. The responsibilities of the anesthesiologist or anesthetist include:

(1) Providing a smooth induction of the patient’s anesthesia in order to prevent pain.

(2) Maintaining satisfactory degrees of relaxation of the patient for the duration of the surgical procedure.

(3) Continuous monitoring of the physiologic status of the patient for the duration of the surgical procedure.

(4) Continuous monitoring of the physiologic status of the patient to include oxygen exchange, systemic circulation, neurologic status, and vital signs.

(5) Advising the surgeon of impending complications and independently intervening as necessary.

d. Scrub Nurse/Assistant. The scrub nurse or scrub assistant is a nurse or surgical technician who prepares the surgical set-up, maintains surgical asepsis while draping and handling instruments, and assists the surgeon by passing instruments, sutures, and supplies. The scrub nurse must have extensive knowledge of all instruments and how they are used. In the Army, the Operating Room Technician (MOS 91D) often fills this role. The scrub nurse or assistant wears sterile gown, cap, mask, and gloves.

e. Circulating Nurse. The circulating nurse is a professional registered nurse who is liaison between scrubbed personnel and those outside of the operating room. The circulating nurse is free to respond to request from the surgeon, anesthesiologist or anesthetist, obtain supplies, deliver supplies to the sterile field, and carry out the nursing care plan. The circulating nurse does not scrub or wear sterile gloves or a sterile gown. Other responsibilities include:

(1) Initial assessment of the patient on admission to the operating room, helping monitoring the patient.

(2) Assisting the surgeon and scrub nurse to don sterile gowns and gloves.

(3) Anticipating the need for equipment, instruments, medications, and blood components, opening packages so that the scrub nurse can remove the sterile supplies, preparing labels, and arranging for transfer of specimens to the laboratory for analysis.

(4) Saving all used and discarded gauze sponges, and at the end of the operation, counting the number of sponges, instruments, and needles used during the operation to prevent the accidental loss of an item in the wound.

8-7. MAJOR CLASSIFICATIONS OF ANESTHETIC AGENTS

a. There are three major classifications of anesthetic agents: general anesthetic, regional anesthetic, and local anesthetic. A general anesthetic produces loss of consciousness and thus affects the total person. When the patient is given drugs to produce central nervous system depression, it is termed general anesthesia.

(1) There are three phases of general anesthesia: induction, maintenance, and emergence. Induction, (rendering the patient unconscious) begins with administration of the anesthetic agent and continues until the patient is ready for the incision. Maintenance (surgical anesthesia) begins with the initial incision and continues until near completion of the procedure. Emergence begins when the patient starts to come out from under the effects of the anesthesia and usually ends when the patient leaves the operating room. The advantage of general anesthesia is that it can be used for patients of any age and for any surgical procedure, and leave the patient unaware of the physical trauma. The disadvantage is that it carries major risks of circulatory and respiratory depression.

(2) Routes of administration of a general anesthetic agent are rectal (which is not used much in today’s medical practices), intravenous infusion, and inhalation. No single anesthetic meets the criteria for an ideal general anesthetic. To obtain optimal effects and decrease likelihood of toxicity, administration of a general anesthetic requires the use of one or more agents. Often an intravenous drug such as thiopental sodium (Pentothal) is used for induction and then supplemented with other agents to produce surgical anesthesia. Inhalation anesthesia is often used because it has the advantage of rapid excretion and reversal of effects.

(3) Characteristics of the ideal general anesthetic are:

(a) It produces analgesia.

(b) It produces complete loss of consciousness.

(c) It provides a degree of muscle relaxation.

(d) It dulls reflexes.

(e) It is safe and has minimal side effects.

(4) General anesthesia is used for major head and neck surgery, intracranial surgery, thoracic surgery, upper abdominal surgery, and surgery of the upper and lower extremities.

b. A regional or block anesthetic agent causes loss of sensation in a large region of the body. The patient remains awake but loses sensation in the specific region anesthetized. In some instances, reflexes are lost also. When an anesthetic agent is injected near a nerve or nerve pathway, it is termed regional anesthesia.

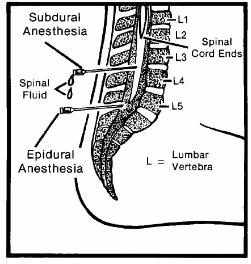

(1) Regional anesthesia may be accomplished by nerve blocks, or subdural or epidural blocks (see figure 8-3).

(2) Nerve blocks are done by injecting a local anesthetic around a nerve trunk supplying the area of surgery such as the jaw, face, and extremities.

(3) Subdural blocks are used to provide spinal anesthesia. The injection of an anesthetic, through a lumbar puncture, into the cerebrospinal fluid in the subarachnoid space causes sensory, motor and autonomic blockage, and is used for surgery of the lower abdomen, perineum, and lower extremities. Side effects of spinal anesthesia include headache, hypotension, and urinary retention.

(4) For epidural block, the agent is injected through the lumbar interspace into the epidural space, that is, outside the spinal canal.

c. Local anesthesia is administration of an anesthetic agent directly into the tissues. It may be applied topically to skin surfaces and the mucous membranes in the nasopharynx, mouth, vagina, or rectum or injected intradermally into the tissue. Local infiltration is used in suturing small wounds and in minor surgical procedures such as skin biopsy. Topical anesthesia is used on mucous membranes, open skin surfaces, wounds, and burns. The advantage of local anesthesia is that it acts quickly and has few side-effects.

8-8. SELECTION OF AN ANESTHETIC AGENT

a. Depending on its classification, anesthesia produces states such as narcosis (loss of consciousness), analgesia (insensibility to pain), loss of reflexes, and relaxation. General anesthesia produces all of these responses. Regional anesthesia does not cause narcosis, but does result in analgesia and reflex loss. Local anesthesia results in loss of sensation in a small area of tissue.

b. The choice of route and the type of anesthesia is primarily made by the anesthetist or anesthesiologist after discussion with the patient. Whether by intravenous, inhalation, oral, or rectal route, many factors effect the selection of an anesthetic agent:

(1) The type of surgery.

(2) The location and type of anesthetic agent required.

(3) The anticipated length of the procedure.

(4) The patient’s condition.

(5) The patient’s age.

(6) The patient’s previous experiences with anesthesia.

(7) The available equipment.

(8) Preferences of the anesthesiologist or anesthetist and the patient.

(9) The skill of the anesthesiologist or anesthetist.

c. Factors considered by the anesthetist or anesthesiologist when selecting an agent are the smoking and drinking habits of the patient, any medications the patient is taking, and the presence of disease. Of particular concern are pulmonary function, hepatic function, renal function, and cardiovascular function.

(1) Pulmonary function is adversely affected by upper respiratory tract infections and chronic obstructive lung diseases such as emphysema, especially when intensified by the effects of general anesthesia. These conditions also predispose the patient to postoperative lung infections.

(2) Liver diseases such as cirrhosis impair the ability of the liver to detoxify medications used during surgery, to produce the prothrombin necessary for blood clotting, and to metabolize nutrients essential for healing following surgery.

(3) Renal insufficiency may alter the excretion of drugs and influence the patient’s response to the anesthesia. Regulation of fluids and electrolytes, as well as acid-base balance, may be impaired by renal disease.

(4) Well-controlled cardiac conditions pose minimal surgical risks. Severe hypertension, congestive heart failure, or recent myocardial infarction drastically increase the risks.

d. Medications, whether prescribed or over-the-counter, can affect the patient’s reaction to the anesthetic agent, increase the effects of the anesthesia, and increase the risk from the stress of surgery. Medication is usually withheld when the patient goes to surgery; but some specific medications are given even then. For example, patients with cardiovascular problems or diabetes mellitus may continue to receive their prescribed medications.

(1) Because some medications interact adversely with other medications and with anesthetic agents, preoperative assessment should include a thorough medication history. Patients may be taking medication for conditions unrelated to the surgery, and are unaware of the potential for adverse reactions of these medications with anesthetic agents.

(2) Drugs in the following categories increase surgical risk.

(a) Adrenal steroids–abrupt withdrawal may cause cardiovascular collapse in long-term users.

(b) Antibiotics–may be incompatible with anesthetic agent, resulting in untoward reactions. Those in mycin group may cause respiratory paralysis when combined with certain muscle relaxants used during surgery.

(c) Anticoagulants–may precipitate hemorrhage.

(d) Diuretics–may cause electrolyte (especially potassium) imbalances, resulting in respiratory depression from the anesthesia.

(e) Tranquilizers–may increase the hypotensive effect of the anesthetic agent, thus contributing to shock.

8-9. REASONS FOR SURGICAL INTERVENTION

Descriptors used to classify surgical procedures include ablative, diagnostic, constructive, reconstructive, palliative, and transplant. These descriptors are directly related to the reasons for surgical intervention:

a. To cure an illness or disease by removing the diseased tissue or organs.

b. To visualize internal structures during diagnosis.

c. To obtain tissue for examination.

d. To prevent disease or injury.

e. To improve appearance.

f. To repair or remove traumatized tissue and structures.

g. To relieve symptoms or pain.

SECTION III. RECOVERY ROOM CARE

8-10. THE RECOVERY ROOM

a. The recovery room is defined as a specific nursing unit, which accommodates patients who have undergone major or minor surgery. Following the operation, the patient is carefully moved from the operating table to a wheeled stretcher or bed and transferred to the recovery room. The patient usually remains in the recovery room until he begins to respond to stimuli. General nursing goals of care for a patient in the recovery room are:

(1) To support the patient through his state of dependence to independence. Surgery traumatizes the body, decreasing its energy and resistance. Anesthesia impairs the patient’s ability to respond to environmental stimuli and to help himself. An artificial airway is usually maintained in place until reflexes for gagging and swallowing return. When the reflexes return, the patient usually spits out the airway. Position the unconscious patient with his head to the side and slightly down. This position keeps the tongue forward, preventing it from blocking the throat and allows mucus or vomitus to drain out of the mouth rather than down the respiratory tree. Do not place a pillow under the head during the immediate postanesthetic stage. Patients who have had spinal anesthetics usually lie flat for 8 to 12 hours. The return of reflexes indicates that anesthesia is ending. Call the patient by name in a normal tone of voice and tell him repeatedly that the surgery is over and that he is in the recovery room.

(2) To relieve the patient’s discomfort. Pain is usually greatest for 12 to 36 hours after surgery, decreasing on the second and third post-op day. Analgesics are usually administered every 4 hours the first day. Tension increases pain perception and responses, thus analgesics are most effective if given before the patient’s pain becomes severe. Analgesics may be administered in patient controlled infusions.

(3) Early detection of complications. Most people recover from surgery without incident. Complications or problems are relatively rare, but the recovery room nurse must be aware of the possibility and clinical signs of complications.

(4) Prevention of complications. Complications that should be prevented in the recovery room are respiratory distress and hypovolemic shock.

b. The difference between the recovery room and surgical intensive care are:

(1) The recovery room staff supports patients for a few hours until they have recovered from anesthesia.

(2) The surgical intensive care staff supports patients for a prolonged stay, which may last 24 hours or longer.

8-11. RESPIRATORY DISTRESS

a. Respiratory distress is the most common recovery room emergency. It may be caused by laryngospasm, aspiration of vomitus, or depressed respirations resulting from medications.

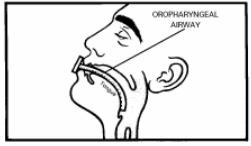

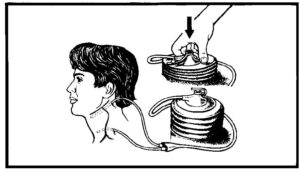

(1) A laryngospasm is a sudden, violent contraction of the vocal cords; a complication, which may happen after the patient’s endotracheal tube, is removed. During the surgical procedure with general anesthesia, an endotracheal tube is inserted to maintain patent air passages. The endotracheal tube may be connected to a mechanical ventilator. Upon completion of the operation, the endotracheal tube is removed by the anesthesiologist or anesthetist and replaced by an oropharyngeal airway (figure 8-4).

(2) Swallowing and cough reflexes are diminished by the effects of anesthesia and secretions are retained. To prevent aspiration, vomitus or secretions should be removed promptly by suction.

(3) Ineffective airway clearance may be related to the effects of anesthesia and drugs that were administered before and during surgery. If possible, an unconscious or semiconscious patient should be placed in a position that allows fluids to drain from the mouth.

b. After removal of the endotracheal tube by the anesthesiologist or anesthetist, an oropharyngeal airway is inserted to prevent the tongue from obstructing the passage of air during recovery from anesthesia. The airway is left in place until the patient is conscious.

8-12. PREVENTION OF RESPIRATORY DISTRESS

a. Monitor respiratory status as frequently as prescribed. Respiratory function is assessed by monitoring the patient’s respiratory rate, rhythm, and depth, and by observing skin color. The following observations indicate ineffective ventilation:

(1) Restlessness and apprehension.

(2) Unequal chest expansion with use of accessory muscles.

(3) Shallow, noisy respirations.

(4) Cyanosis.

(5) Rapid pulse rate.

b. Report labored respirations to supervisor.

c. Report shallow, rapid respirations to the supervisor.

d. Maintain a patent airway with or without an oropharyngeal tube.

e. Maintain the patient in a position to facilitate lung expansion, usually in Fowler’s position.

f. Administer oxygen as ordered.

g. Prevent aspiration of vomitus.

(1) Maintain the position of the patient’s head to one side and place an emesis basin under the cheek, extending from just below the eye to the lower edge of the bottom lip.

(2) Wipe vomitus or secretions from the nose or mouth in order to avoid possible aspiration of these fluids into the lungs.

h. Suction the patient either through the nose or mouth as ordered.

8-13. HYPOVOLEMIC SHOCK

a. When there is an alteration in circulatory control or a loss of circulating fluid, the body’s reaction is shock. The most common type of shock seen in the postoperative patient is hypovolemic shock, which occurs with a decrease in blood volume. Common signs and symptoms are hypotension; cold, clammy skin; a weak, thready, and rapid pulse; deep, rapid respirations; decreased urine output; thirst; apprehension; and restlessness.

b. Hemorrhage, which is an excessive blood loss, may lead to hypovolemic shock. Postoperative hemorrhage may occur from a slipped suture, a dislodged clot in a wound, or stress on the operative site. It also may result from the pathological disorder for which the patient is being treated, or be caused by certain medications.

c. The primary nursing care goal is to maintain tissue perfusion by eliminating the cause of the shock.

(1) The blood loss from surgery that causes hypovolemic shock may be internal or external.

(2) The loss of fluid or blood volume does not have to be rapid or copious amounts to cause shock.

d. The primary purposes of care for the patient having a hemorrhage include stopping the bleeding and replacing blood volume.

8-14. DETECTION OF PENDING HYPOVOLEMIC SHOCK

a. Inspect the surgical dressing frequently and report any bleeding to the supervisor. Also inspect the bedding beneath the patient because blood may drain down the sides of a large dressing and pool under the patient. When reporting bleeding, note the color of the blood. Bright red blood signifies fresh bleeding. Dark, brownish blood indicates that the bleeding is not fresh.

b. Outline the perimeter of the blood stain on the original dressing. Reinforce the original dressing, and make note on the dressing of the date and time the outline was made.

c. Document your observations and the action taken in the nurse’s notes.

d. Monitor the patient’s vital signs as ordered and report any of the following abnormalities to the supervisor.

(1) A drop in blood pressure (systolic reading below 90 in an adult indicates possible shock; systolic below 80 means actual shock).

(2) A rapid, weak pulse.

(3) Restlessness.

(4) Cool, moist, pale skin.

(5) Tingling of the lips.

(6) Pallor or blueness (cyanosis) of the lips, nailbeds, or conjunctiva (a dark-skinned persons lips will appear a dusky gray).

e. Administer narcotics only after checking doctor’s orders and consulting with supervisor. If shock is imminent, it may be precipitated by administration of narcotics.

f. Administer fluids to replace volume in accordance with the doctor’s orders. The doctor may order that blood volume be replaced by intravenous (IV) fluids, plasma expanders, or whole blood products.

8-15. GENERAL NURSING CARE OF A PATIENT IN THE RECOVERY ROOM

a. When the patient is moved to the recovery room, every effort should be made to avoid unnecessary strain, exposure, or possible injury. The anesthesiologist or anesthetist goes to the recovery room with the patient, reports his condition, leaves postoperative orders and any special instructions, and monitors his condition until that responsibility is transferred to the recovery room nurses. The recovery room nurse should check the doctor’s orders and carry them out immediately.

b. Patients are concentrated in a limited area to make it possible for one nurse to give close attention to two or three patients at the same time. Each patient unit has a recovery bed equipped with side rails, poles for IV medications, and a chart rack. The bed is easily moved and adjusted. Each unit has outlets for piped-in oxygen, suction, and blood pressure apparatus. The following are nursing implications for the general care of a patient in the recovery room:

(1) Maintain proper functioning of drains, tubes, and intravenous infusions. Prevent kinking or clogging that interferes with adequate flow of drainage through catheters and drainage tubes.

(2) Monitor intake and output precisely, to include all Intravenous fluids and blood products, urine, vomitus, nasogastric tube drainage, and wound drainage.

(3) Observe and document the patient’s level of consciousness. The return of central nervous system function is assessed through response to stimuli and orientation. Levels of consciousness return in reverse order: unconscious, responds to touch and sound, drowsy, awake but not oriented, and awake and oriented. Specific criteria is usually used for categorizing the recovery room patient.

(a) Comatose — unconscious; unresponsive to stimuli.

(b) Stupor — lethargic and unresponsive; unaware of surroundings.

(c) Drowsy — half asleep, sluggish; responds to touch and sounds.

(d) Alert — able to give appropriate response to stimuli.

(4) Implement safety measures to protect the patient. Keep the side rails raised at all times. Assure that the patient is positioned so that he is not tangled in or laying on IV or drainage tubes. Do not use a head pillow while the patient is unconscious, or for eight hours if the patient had spinal anesthesia. Turn the patient’s head to one side when he is in the supine position so that secretions can drain from the mouth and the tongue will not fall into the throat to block the air passage. When the patient is alert, show him how to use the call bell and place it where it is readily available.

(5) If the patient had a spinal anesthetic, observe and report any feeling or spontaneous movement. Movement usually returns before feeling. Movement returns in the patient’s toes first, and moves upward. As the anesthesia wears off, the patient will begin to have sensation often described as “pins and needles.” Spinal anesthesia wears off slowly. Keep the patient in a supine position for six to eight hours to prevent spinal headache. Turn the patient from side to side and prop up with pillows for a few minutes to relieve pressure on the back, but only if permitted by the doctor.

(6) Prevent nosocomial infections. Wash your hands before and after working with each patient. Maintain aseptic technique for incisional wounds. Turn the patient frequently to prevent respiratory infections. When the patient is alert, encourage and assist him to cough and take deep breaths several times each hour.

(7) If possible, engage the patient in a conversation to observe his level of orientation. Take into consideration each patient’s normal responses due to various physical factors.

(8) Provide emotional support to the patient and his family. When the patient is alert, tell him that he is in the recovery room and that you are always nearby to help him. Reinforce any information that may have been provided by the surgeon. To decrease anxiety and increase lung expansion, encourage conversation with the patient. Use this opportunity to patient teach by explaining what you are about to do in brief, simple sentences. If family members are permitted in the recovery room, stay with them as they visit. They may be frightened of the environment and by their loved one’s appearance.

(9) When the patient’s physical status and level of consciousness are stable, the surgeon clears the patient for transfer to his room. Call the nursing unit and give a verbal report to include the following.

(a) Patient’s name

(b) Type of surgery.

(c) Mental alertness.

(d) Care given in the recovery room.

(e) Vital signs, at what time they were taken, and any symptoms of complications.

(f) Presence, type and functional status of intravenous fluids, and any suction or drainage systems.

(g) Whether or not the patient has voided, if a catheter is not in place.

(h) Any medications given in the recovery room.

(10) Document all necessary information in the nurse’s notes and transfer the patient to the unit in accordance with local standing operating procedures (SOP).

SECTION IV. POSTOPERATIVE PATIENT CARE

8-16. RECEIVING THE POST-OP PATIENT

a. The nursing process is used during all phases of perioperative care, with emphasis on the special and unique needs of each patient in each phase. Ongoing postoperative care is planned to ease the patient’s recovery from surgery. The nursing care plan includes promoting physical and psychological health, preventing complications, and teaching self-care for the patient’s return home. While the patient is in the operating and recovery room, an unoccupied bed is prepared. The top linen is folded to the side or bottom of the bed. Absorbent pads are placed over the drawsheet to protect bottom linens. Equipment and supplies, such as blood pressure apparatus, tissues, an emesis basin, and a pole for hanging the intravenous fluid containers, should be in place when the patient returns. The unit nurse should be informed by the recovery room nurse if other items, such as suction or oxygen equipment will be needed.

b. Postoperative patient care begins with the unit nurse assisting recovery room personnel in transferring the patient to the bed in his room. Data from the preoperative and intraoperative phases is used to make an initial assessment. The assessment is often combined with implementation of the doctor’s postoperative orders and should include the following.

(1) Position and safety. Place the patient in the position ordered by the doctor. The patient who has had spinal anesthesia may have to remain lying flat for several hours. If the patient is not fully conscious, place him in a side-lying position and raise the side rails.

(2) Vital signs. Take vital signs and note alterations from postoperative and recovery room data, as well as any symptoms of complications.

(3) Level of consciousness. Assess the patient’s reaction to stimuli and ability to move extremities. Help the patient become oriented by telling him that his surgery is over and that he is back in his room.

(4) Intravenous fluids. Assess the type and amount of solution, the tubing, and the infusion site. Count the rate at which the intravenous fluid is infusing.

(5) Wound. Check the patient’s dressing for drainage. Note the color and amount, if any. If there is a large amount of drainage or bright red bleeding, report this immediately to the supervisor.

(6) Drains and tubes. Assess indwelling urinary catheter, gastrointestinal suction, and other tubes for drainage, patency, and amount of output. Be sure drainage bags are hanging properly and suction is functioning. If the patient is receiving oxygen, be sure that the application and flow rate is as ordered.

(7) Color and temperature of skin. Feel the patient’s skin for warmth and perspiration. Observe the patient for paleness or cyanosis.

(8) Comfort. Assess the patient for pain, nausea, and vomiting. If the patient has pain, note the location, duration and intensity. Determine from recovery room data if analgesics were given and at what time.

c. Make sure that the patient is warm and comfortable, and allow family members to visit after you have completed the initial assessment.

8-17. THE EFFECTS OF ANESTHESIA

a. The effects of anesthesia tend to last well into the postoperative period. Anesthetic agents may depress respiratory function, cardiac output, peristalsis and normal functioning of the gastrointestinal tract, and may temporarily depress bladder tone and response.

(1) Effects on the respiratory system. Pulmonary efficiency is reduced, increasing the possibility of postoperative pneumonia. Pneumonia is an inflammation of the alveoli resulting from an infectious process or the presence of foreign material. Pneumonia can occur postoperatively because of aspiration, infection, depressed cough reflex, immobilization, dehydration, or increased secretions from anesthesia. Signs and symptoms common to pneumonia are an elevated temperature, chills, cough producing purulent or rusty sputum, dyspnea, and chest pain. The purposes of medical intervention is to treat the underlying infection, maintain respiratory status, and prevent the spread of infection.

(2) Effects on the cardiovascular system. Anesthesia may affect cardiac output, thus increasing the possibility of unstable blood pressure. Shock is the reaction to acute peripheral circulatory failure because of an alteration in circulatory control or to a loss of circulating fluid.

(3) Effects on the urinary system. Anesthesia can cause urinary retention. Decreased fluid intake can lead to dehydration. Assess urinary elimination status by measuring intake and output. Offer the bedpan or urinal at regular intervals to promote voiding. If catheter is present, monitor drainage.

(4) Effects on gastrointestinal system. Anesthesia slows or stops the peristaltic action of the intestines resulting in constipation, abdominal distention, and flatulence. Anesthesia may also cause nausea and vomiting resulting in a fluid imbalance. Ordinarily, intravenous infusions are used while the patient takes nothing by mouth until bowel sounds are heard upon auscultation. Observe the patient for abdominal distention. Have the patient move about in bed and walk to help promote the movement and expulsion of the flatus.

b. A wide variety of factors increase the risk of postoperative complications. Comfort is often the priority for the patient following surgery. Nausea, vomiting, and other effects of anesthesia cause alterations in comfort. The nursing care plan should include activities to meet the patient’s needs while helping him cope with these alterations.

8-18. OTHER POSTOPERATIVE COMPLICATIONS

a. Atelectasis is the incomplete expansion or collapse of alveoli with retained mucus, involving a portion of the lung and resulting in poor gas exchange. Signs and symptoms of atelectasis include dyspnea, cyanosis, restlessness, apprehension, crackles, and decreased lung sounds over affected areas. The primary purposes of care for the patient with atelectasis are to ensure oxygenation of tissue, prevent further atelectasis, and expand the involved lung tissue.

b. Hypovolemic shock is the type most commonly seen in the postoperative patient. Hypovolemic shock occurs when there is a decrease in blood volume. Signs and symptoms are hypotension; cold, clammy skin; a weak, thready and rapid pulse; deep, rapid respirations; decreased urine output; thirst; restlessness; and apprehension.

c. Hemorrhage is excessive blood loss, either internally or externally. Hemorrhage may lead to hypovolemic shock.

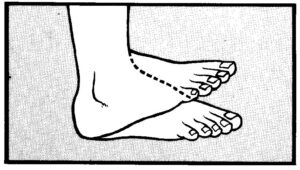

d. Thrombophlebitis is inflammation of a vein associated with thrombus (blood clot) formation. Thrombophlebitis is more commonly seen in the legs of a postoperative patient. Signs and symptoms are elevated temperature, pain and cramping in the calf or thigh of the involved extremity, redness and swelling in the affected area, and pain with dorsiflexion of the foot (figure 8-5). Care for the patient with thrombophlebitis includes preventing a clot from breaking loose and becoming an embolus that travels to the lungs, heart, or brain and preventing other clot formation.

8-19. WOUND COMPLICATIONS

a. Nursing implications in relation to prevention and early detection of wound complications include assessing vital signs, especially monitoring an elevated temperature; assisting the patient to maintain nutritional status, and use of medical asepsis. The integumentary system is the body’s natural barrier against invasion of infectious microorganisms. Possible negative effects of surgery on the integumentary system include wound infection, dehiscence, and evisceration.

(1) Wound infection. Surgical wounds are assessed for possible complications by inspection (sight and smell) and palpation for appearance, drainage, and pain. The wound edges should be clean and well approximated with a crust along the wound edges. If infection is present, the wound is slightly swollen, reddened, and feels hot. Hand washing is the most frequently used medical aseptic practice and the single most effective way to prevent the spread of microorganisms that cause wound infections.

(2) Dehiscence. Dehiscence is the separation of wound edges without the protrusion of organs. An appreciable increase in serosanguinous fluid on the wound dressing (usually between the 6th and 8th postoperative day) is a clue to impending dehiscence.

(3) Evisceration. Evisceration is the separation of wound edges with the protrusion of organs through the incision. Wound disruption is often preceded by sudden straining. The patient may feel that something “gave way.”

b. If dehiscence is suspected or occurs, place the patient on complete bed rest in a position that puts the least strain on the operative area and notify the surgeon. If evisceration occurs, cover the wound area with sterile towels soaked in saline solution and notify the surgeon immediately. These are both emergency situations that require prompt surgical repair.

c. Predisposing factors and causes of wound separation are:

(1) Infection.

(2) Malnutrition , particularly insufficient protein and vitamin C, which interferes with the normal healing process.

(3) Defective suturing or allergic reaction to the suture material.

(4) Unusual strain on the wound from severe vomiting, coughing, or sneezing.

(5) Extreme obesity, an enlarged abdomen, or an abdomen weakened by prior surgeries may also contribute to the occurrence of wound dehiscence and evisceration.

8-20. WOUND CLOSURES AND HEALING

a. Any wound or injury results in repair to the damaged skin and underlying structures. All wounds follow the same phases in healing, although differences occur in the length of time required for each phase of the healing process and in the extent of granulation tissue formed. Wounds heal by one of three processes: primary, secondary, or tertiary intention.

(1) Primary intention is the ideal method of wound healing. The wound is a clean, straight line with little loss of tissue. All wound edges are well approximated and sutured closed. It is a form of connective tissue repair that involves proliferation of fibroblasts and capillary buds and the subsequent development of collagen to produce a scar. Most surgical incisions and small sutured lacerations heal by primary intention. These wounds normally heal rapidly with minimal scarring.

(2) Secondary intention is healing of an open wound where there has been a significant loss of tissue. The edges may be so far apart that they cannot be pulled together satisfactorily. Infection may also cause a separation of tissue surfaces and prevent wound approximation. The wound is usually not sutured closed. Granulation tissue is allowed to form, followed by a large scar formation. Epithelium ultimately grows over the scar tissue.

(3) Tertiary intention is delayed primary closure. The wound is left open for several days and is then sutured closed. There is increased risk of infection and inflammatory reaction. The wound is usually one that is fairly deep and likely to contain accumulating fluid. A drain or pack gauze may be placed into the wound to provide for drainage.

b. The greater the tissue damage, the greater the demand on the body’s reparative processes. The ability to close an open wound affects the rate of healing and prevention of complications.

8-21. FACTORS WHICH MAY IMPAIR WOUND HEALING

a. Developmental Stage. Children and adults in good health heal more rapidly than do elderly persons who have undergone physiologic changes that result in diminished fibroblastic activity and diminished circulation. Older adults are more likely to have chronic illnesses that cause pathologic changes that may impair wound healing.

b. Poor Circulation and Oxygenation. Blood supply to the affected area may be diminished in elderly persons and in those with peripheral vascular disorders, cardiovascular disorders, hypertension, or diabetes mellitus. Oxygenation of tissues is decreased in persons who smoke, and in those with anemia or respiratory disorders. Obesity slows wound healing because of the presence of large amounts of fat, which has fewer blood vessels.

c. Physical and Emotional Wellness. Chronic physical illness and severe emotional stress have a negative affect on wound healing. Patients who have inadequate nutrition, those who are taking steroid drugs, and those who are receiving postoperative radiation therapy have a higher risk of wound complications and impaired wound healing.

d. Condition of the Wound. The specific condition of the wound affects the healing process. Wounds that are infected or contain foreign bodies (including drains, pack gauze) heal slowly.

8-22. WOUND DRAINS

a. Inserting Drains. The use of drains, tubes, and suction devices at the wound site is often necessary to promote healing. A drain or tube is inserted into or near a wound after the surgical procedure is completed. One end of a tube or drain is placed in or near the incision when it is anticipated that fluid will collect in the closed area and delay healing. The other tube end is passed through the incision or through a separate opening called a stab wound. Tubes that are to be connected to suction or have a built-in reservoir are sutured to the skin. It is important that you know the type of drain or tube in use so that patency and placement can be accurately assessed.

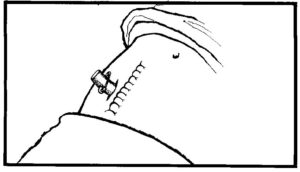

b. Penrose Drain (figure 8-6). This is the most commonly used drain. It is made of flexible, soft rubber and causes little tissue reaction. It acts by drawing any pus or fluid along its surfaces through the incision or through a stab wound adjacent to the main incision. It has a large safety pin outside the wound to maintain its position. To facilitate drainage and healing of tissues from the inside to the outside, the tube is often pulled out and shortened 1 to 2 inches each day until it falls out. The safety pin should be placed in its new position prior to cutting the drain. Advance the drain with a dressing forceps or hemostat, use surgical scissors to cut excess drain.

c. Jackson-Pratt/Hemovac Closed Suction Device (figure 8-7). Tubes are connected to suction or there is a built-in reservoir to maintain constant low suction. In the operating room, the surgeon places the perforated drainage tubing in the desired area, makes a stab wound, then draws the excess tubing through the wound creating a tightly sealed porthole. The tubing is then attached via an adaptor to the suction device. To establish negative pressure, compress the device and place the plug in the air hole.

8-23. POSTOPERATIVE PATIENT CARE ACCORDING TO BODY SYSTEM

a. Respiratory System. The cough reflex is suppressed during surgery and mucous accumulates in the trachea and bronchi. After surgery, respiration is less effective because of the anesthesia and pain medication, and because deep respirations cause pain at the incision site. As a result, the alveoli do not inflate and may collapse, and retained secretions increase the potential for respiratory infection and atelectasis.

(1) Turn the patient as ordered.

(2) Ambulate the patient as ordered.

(3) If permitted, place the patient in a semi-Fowler’s position, with support for the neck and shoulders, to aid lung expansion.

(4) Reinforce the deep breathing exercises the patient was taught preoperatively. Deep breathing exercises hyperventilate the alveoli and prevent their collapse, improve lung expansion and volume, help to expel anesthetic gases and mucus, and facilitate oxygenation of tissues. Ask the patient to:

(a) Exhale gently and completely.

(b) Inhale through the nose gently and completely.

(c) Hold his breath and mentally count to three.

(d) Exhale as completely as possible through pursed lips as if to whistle.

(e) Repeat these steps three times every hour while awake.

(5) Coughing, in conjunction with deep breathing, helps to remove retained mucus from the respiratory tract. Coughing is painful for the postoperative patient. While in a semi-Fowler’s position, the patient should support the incision with a pillow or folded bath blanket and follow these guidelines for effective coughing:

(a) Inhale and exhale deeply and slowly through the nose three times.

(b) Take a deep breath and hold it for 3 seconds.

(c) Give two or three “hacking” coughs while exhaling with the mouth open and the tongue out.

(d) Take a deep breath with the mouth open.

(e) Cough deeply once or twice.

(f) Take another deep breath.

(g) Repeat these steps every 2 hours while awake.

(6) An incentive spirometer may be ordered to help increase lung volume, inflation of alveoli, and facilitate venous return. Most patients learn to use this device and can carry out the procedure without a nurse in attendance. Monitor the patient from time to time to motivate them to use the spirometer and to be sure that they use it correctly.

(a) While in an upright position, the patient should take two or three normal breaths, then insert the spirometer’s mouthpiece into his mouth.

(b) Inhale through the mouth and hold the breath for 3 to 5 seconds.

(c) Exhale slowly and fully.

(d) Repeat this sequence 10 times during each waking hour for the first 5 post-op days. Do not use the spirometer immediately before or after meals.

b. Cardiovascular System. Venous return from the legs slows during surgery and may actually decrease in some surgical positions. With circulatory stasis of the legs, thrombophlebitis and emboli are potential complications of surgery. Venous return is increased by flexion and contraction of the leg muscles.

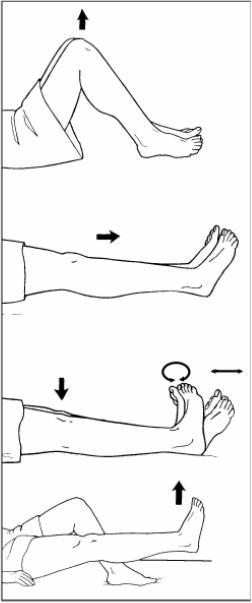

(1) To prevent thrombophlebitis, instruct the patient to exercise the legs while on bedrest. Leg exercises are easier if the patient is in a supine position with the head of the bed slightly raised to relax abdominal muscles. Leg exercises (figure 8-8) should be individualized using the following guidelines.

(a) Flex and extend the knees, pressing the backs of the knees down toward the mattress on extension.

(b) Alternately, point the toes toward the chin (dorsiflex) and toward the foot of the bed (plantar flex); then, make a circle with the toes.

(c) Raise and lower each leg, keeping the leg straight.

(d) Repeat leg exercises every 1 to 2 hours.

(2) Ambulate the patient as ordered.

(a) Provide physical support for the first attempts.

(b) Have the patient dangle the legs at the bedside before ambulation.

(c) Monitor the patient’s blood pressure while he dangles.

(d) If the patient is hypotensive or experiences dizziness while dangling, do not ambulate. Report this event to the supervisor.

c. Urinary System. Patients who have had abdominal surgery, particularly in the lower abdominal and pelvic regions, often have difficulty urinating after surgery. The sensation of needing to urinate may temporarily decrease from operative trauma in the region near the bladder. The fear of pain may cause the patient to feel tense and have difficulty urinating.

(1) If the patient does not have a catheter, and has not voided within eight hours after return to the nursing unit, report this event to the supervisor.

(2) Palpate the patient’s bladder for distention and assess the patient’s response. The area over the bladder may feel rounder and slightly cooler than the rest of the abdomen. The patient may tell you that he feels a sense of fullness and urgency.

(3) Assist the patient to void.

(a) Assist the patient to the bathroom or provide privacy.

(b) Position the patient comfortably on the bedpan or offer the urinal.

(4) Measure and record urine output. If the first urine voided following surgery is less than 30 cc, notify the supervisor.

(5) If there is blood or other abnormal content in the urine, or the patient complains of pain when voiding, report this to the supervisor.

(6) Follow nursing unit standing operating procedures (SOP) for infection control, when caring for the patient with a Foley catheter.

d. Gastrointestinal System. Inactivity and altered fluid and food intake during the perioperative period alter gastrointestinal activities. Nausea and vomiting may result from an accumulation of stomach contents before peristalsis returns or from manipulation of organs during the surgical procedure if the patient had abdominal surgery.

(1) Report to the supervisor if the patient complains of abdominal distention.

(2) Ask the patient if he has passed gas since returning from surgery.

(3) Auscultate for bowel sounds. Report your assessment to the supervisor, and document in nursing notes.

(4) Assess abdominal distention, especially if bowel sounds are not audible or are high-pitched, indicating an absence of peristalsis.

(5) Provide a privacy so that the patient will feel comfortable expelling gas.

(6) Encourage food and fluid intake when the patient in no longer NPO.

(7) Ambulate the patient to assist peristalsis and help relieve gas pain, which is a common postoperative discomfort.

(8) Instruct the patient to tell you of his first bowel movement following surgery. Record the bowel movement on the intake and output (I&O) sheet.

(9) If nursing measures are not effective, the doctor may order medication or an enema to facilitate peristalsis and relieve distention. A last measure may require the insertion of a nasogastric or rectal tube.

(10) Document nursing measures and the results in the nursing notes.

e. Integumentary System. Follow doctor’s orders for wound care, wound irrigations and cultures. In addition to assessment of the surgical wound, you should evaluate the patient’s general condition and laboratory test results. If the patient complains of increased or constant pain from the wound, or if wound edges are swollen or there is purulent drainage, further assessment should be made and your findings reported and documented. Generalized malaise, increased pain, anorexia, and an elevated body temperature and pulse rate are indicators of infection. Important laboratory data include an elevated white blood cell count and the causative organism if a wound culture is done. Staples or sutures are usually removed by the doctor using sterile technique. After the staples or sutures are removed, the doctor may apply Steri-Strip® to the wound to give support as it continues to heal.

(1) There are two methods of caring for wounds: the open method, in which no dressing is used to cover the wound, and the closed method, in which a dressing is applied. The basic objective of wound care is to promote tissue repair and regeneration, so that skin integrity is restores. Dressings have advantages and disadvantages.

(a) Advantages. Dressings absorb drainage, protect the wound from injury and contamination, and provide physical, psychological, and aesthetic comfort for the patient.

(b) Disadvantages. Dressings can rub or stick to the wound, causing superficial injury. Dressings create a warm, damp, and dark environment conducive to the growth of organisms and resultant infection.

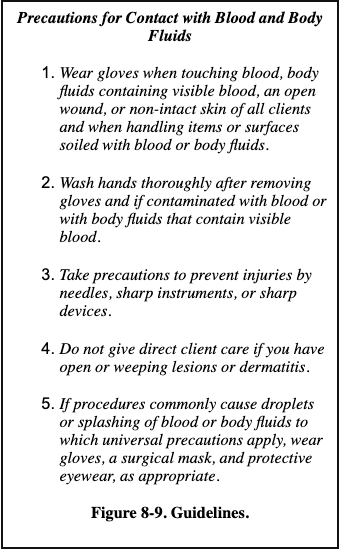

(2) At some time, most wounds are covered with a dressing and you may be responsible for changing the dressing. First, gather needed supplies. Items may be packaged individually or all necessary items may be in a sterile dressing tray. Some surgical units have special dressing carts, with agents needed to clean the wound, and materials to cover and secure the dressing. Next, prepare the patient for the dressing change by explaining what will be done, providing privacy for the procedure, and assisting the patient to a position that is comfortable for him and for you. Finally, use appropriate aseptic techniques when changing the dressing and follow precautions for contact with blood and body fluids. The most common cause of nosocomial infections is carelessness in observing medical and surgical asepsis when changing dressings. It is especially important to wash hands thoroughly before and after changing dressings and to follow the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) guidelines (figure 8-9).

8-24. GENERAL POSTOPERATIVE NURSING IMPLICATIONS

a. Monitor vital signs as ordered.

b. Report elevated temperature and rapid/weak pulse immediately to supervisor (infection).

c. Report lowered blood pressure and increased pulse to supervisor (hypovolemic shock).

d. Administer analgesics as ordered.

e. Apply all nursing implications related to the patient receiving analgesics whether narcotic or nonnarcotic, to include the following.

(1) Check each medication order against the doctor’s order.

(2) Prepare the medications (check labels, accurately calculate dosages, observe proper asepsis techniques with needles and syringes).

(3) Check the patient’s identification wristband to ensure positive identification before administering medications.

(4) Administer the medications. Offer each drug separately if administering more than one drug at the same time.

(5) Remain with the patient and see that the medication is taken. Never leave medications at the bedside for the patient to take later.

(6) Document the medications given as soon as possible.

f. Administer IV fluids as ordered. Maintain and monitor all IV sites. Follow SOP for infection control.

g. Participate with the health team in the patient’s nutrition therapy.

h. Apply all nursing implications related to the patient diets (serving, recording intake, and food tolerance).

i. Coordinate with team leader for “take-home” wound care supplies and prescriptions for self-administration.

j. Prepare the patient and the family for disposition (transfer, return to duty, discharge). Supply the patient or family member with written instructions for:

(1) Wound care.

(2) Medications.

(3) Making outpatient appointments.

(4) An emergency, including the phone numbers for doctors and/or clinics.

k. Document the patient’s disposition in the nurse’s notes in accordance with unit SOP.

8-25. CLOSING

Surgical intervention often alters physical appearance and normal physiological functions and may threaten the patients psychological security. Any or all of these may lead to alterations in the patient’s self-concept and body image. Some surgical patients react to the loss of a body part as to a death. Be aware of the patient’s needs and establish interventions that will support his strengths and effective coping skills. The nursing process is used throughout the perioperative period to provide the patient with individualized care and the knowledge and ability for self-care following disposition.