5-1. Select from a list six factors which influence eating patterns.

5-2. Identify factors, which may alter a hospitalized patient’s eating patterns.

5-3. Identify factors, which may alter a patient’s food intake due to illness.

5-4. Identify reasons that hospitalized patients are at risk of being malnourished.

5-5. Identify nursing interventions, which may help, the patient meets his or her nutritional needs.

5-6 Identify the responsibilities of the practical nurse in relation to diet therapy.

5-7. Identify six reasons for therapeutic diets.

5-8. Select a specialized diet when given a description of the diet contents.

5-9. Identify nursing interventions, which may prepare the patient for meals.

5-1. INTRODUCTION

Food is essential to life. To sustain life, the nutrients in food must perform three functions within the body: build tissue, regulate metabolic processes, and provide a source of energy. A proper diet is essential to good health. A well-nourished person is more likely to be well developed, mentally and physically alert, and better able to resist infectious diseases than one who is not well nourished. Proper diet creates a healthier person and extends the years of normal bodily functions. Diet therapy is the application of nutritional science to promote human health and treat disease.

5-2. FACTORS WHICH INFLUENCE EATING PATTERNS

We all eat certain foods for reasons other than good nutrition and health. Our eating patterns develop as part of our cultural and social traditions and are influenced by our life style and life situation. It is important for the nurse to understand factors, which influence food choice and eating patterns.

a. Social Aspects. Most people prefer to eat with someone, and the patient is probably used to eating meals with his family. In the hospital he is served his food on a tray and left alone. Poor nutrition may be the result.

b. Emotional Aspects. The patient may feel guilty for not eating all the food served, or may overeat just because the food is there. The patient may overeat because he or she feels sad, lonely, or depressed or may refuse to eat for the same reasons. Certain foods may be considered “for babies.” Some foods may be used as rewards.”

c. Food Fads and Fallacies. These are scientifically unsubstantiated, misleading notions or beliefs about certain foods that may persist for a time in a given community or society. Many people follow fad diets or the practice of eating only certain foods. Food fads fall into four basic groups: Food cures, harmful foods, food combinations that restore health or reduce weight, and natural foods that meet body needs and prevent disease.

d. Financial Considerations. The patient’s financial status has a great bearing on eating patterns. Most people in the United States can afford a diet, which includes a variety of foods and a sufficient number of calories. However, many Americans consume an excessive amount of fat and sodium. Excess fat consumption has been shown to be related to the development of heart disease. Excess sodium consumption may be a problem for some patients with hypertension. Many Americans with lower incomes consume a great percentage of their calories in the form of fat, since fat is the least expensive nutrient (when compared to carbohydrate and protein) and provides for greater satiety (feeling of “fullness” after eating) than both carbohydrate and protein.”

e. Physical Condition. The patient may not feel well enough or strong enough to eat. Encourage the patient to eat without forcing him to do so. Encourage him to feed himself, so that he will not feel helpless.

f. Cultural Heritage. Food preferences are closely tied to culture and religion. Understanding these preferences will enable you to assist the patient in reaching and maintaining good nutritional health.

(1) African-Americans. Food habits may be based on West Indian, African, or regional American influences. The majority of African-Americans are lactose intolerant and avoid milk but can tolerate cheese, yogurt, and ice cream. African-Americans who have been in the US for many generations have similar eating patterns to other Americans. Their diets are rich in fat, salt, sugar, and starches. Those who have recently immigrated to the US eat the staple rice and bean combination, yams, and tropical fruits.

(2) Hispanic-Americans. The Hispanic population is thought to be 60 percent Mexican, 18 percent Central and South American, 15 percent Puerto Rican, and 7 percent Cuban. They are a varied group having different food habits.

(a) Mexican-Americans eat tortillas, rice and beans with most meals. Meats are heavily spiced, and often chopped or ground. Adults use limited amounts of milk and milk products, but enjoy sweet baked desserts, sweetened beverages such as hot chocolate and carbonated drinks.

(b) Puerto Ricans tend to adopt American food habits. Traditional meals include white rice cooked with lard and served with beans. Some practice the “hot-cold” theory in the treatment of illness with food.

(c) Cuban-Americans use rice and beans extensively and meat is served if income is sufficient. Children drink milk but adults use milk only in coffee.

(3) Chinese-Americans. A common dietary principle is “Fan-tsai.” Fan is the grain and tsai are the vegetables or other items served at the meal. Chinese-Americans obtain 80 percent of their calories from grains and 20 percent from vegetables, fruits, animal protein, and fats. Most adults dislike milk and cheese. Lactose intolerance is common.

(4) Japanese-American. Most Japanese-American’s eating habits are Westernized. Traditional meals are light and little animal fat is used. The major starch used is rice. Meals contain fish, soup, fresh or pickled vegetables, and tea.

(5) Indian-Americans. Eating patterns vary, depending upon the religion, and the province and climate from which the Indian-American came. If from northern India, wheat is the primary grain used and meat dishes are popular. If from southern India, rice is the primary grain used, the food is highly spiced, and the person will usually be a vegetarian because of Hindu beliefs. Sweets are very sweet and eaten often. Most Indian-American’s eat only two meals daily. Only the right hand is used for eating. Women eat only after men and children have eaten, even if they are ill. Traditional fads and fallacies result in a high rate of stillbirths, low birth weight infants, and a high maternal death rates.

(6) Native-Americans. Because about 200 different tribes of Native Americans exist in the United States, each with its own language, folkways, religion, mores, and patterns of interpersonal relationships, caution needs to be taken in generalizing about Native American culture and food preferences. Various tribal groups differ in their traditional values and beliefs. Each tribe assigns symbolic meanings to foods or other substances. At least one-third of the Native American population is poverty-stricken. Associated with this income level are poor living conditions and malnutrition.

5-3. RELIGION

Cultural and religious practices are often intertwined. Many people refrain from eating certain foods, or eat specific foods in certain combinations, because of their religious beliefs. There are some major religious customs related to diet that, as a nurse, you must be aware of.

a. Hindu. Most Hindus are lacto-ovo vegetarians. They do not use stimulants such as alcohol or coffee.

b. Moslem (Islam). Meat and poultry must be slaughtered according to strict rules. Moslems do not eat pork or pork products. They do not drink alcoholic beverages. They do drink tea. Moslems fast for one month each year, avoiding food from dawn until after dark.

c. Jewish (Orthodox). Orthodox Jews do not eat pork, shellfish, or scavenger fish. They do eat beef, veal, lamb, mutton, goat, venison, chicken, turkey, goose, and pheasant. Meat must be slaughtered by a ritual method. Meat and milk may not be served at the same meal. Meat and dairy foods must be prepared in separate containers and with separate utensils. Certain days of fasting are observed, but a rabbi may excuse an elderly or ill patient.

d. Mormon. Mormons do not drink alcohol, coffee, tea, or caffeine containing carbonated beverages. They do not use extremely hot or cold foods (no ice in beverages).

e. Roman Catholic. Catholics may voluntarily abstain from eating meat on Fridays and during Lent. They do not eat or drink (except water) before taking Holy Communion. They fast on Good Friday and Ash Wednesday, but a priest may excuse the elderly or an ill patient.

f. Seventh Day Adventists. Seventh Day Adventists do not drink alcohol, coffee, or tea. They are usually lacto-ovo vegetarians.

5-4. THE VEGETARIAN

a. Because of the dangers of too much animal protein resulting in health problems or for ecological reasons, many people have chosen to be vegetarians. They do not eat any type of meat. Some vegetarian diets are stricter than others.

(1) Lacto vegetarians eat plant foods and dairy products. They do not eat eggs.

(2) Ovo vegetarians eat plant foods and eggs. They do not eat dairy products.

(3) Lacto-ovo vegetarians eat plant foods, dairy products, and eggs.

(4) Fruitarians consume a diet that consists chiefly of fruits, nuts, olive oil, and honey. They do not eat any animal products.

(5) Vegans eat only plant foods.

b. The greatest concern in the vegetarian diet is attaining adequate amounts of complete protein. This is easy in the lacto-ovo vegetarian diet, but difficult for the vegan. The most efficient protein available is that found in dairy products, eggs, and fish. Among the sources of protein that can be used most efficiently by the body, meat actually ranks third. The second best supply of efficient protein is legumes, soybeans, nuts, and brown rice.

c. Complete proteins are needed to sustain life and to promote growth. Incomplete protein sources can be combined to become a complete protein.

(1) Grain may be combined with brewer’s yeast, with milk and cheese, with nuts and milk or legumes. Examples are cereal and milk, a peanut butter sandwich and milk or yogurt, a cheese sandwich; rice cooked in milk, and baked beans with nut bread.

(2) Grain with dried beans or wheat germ and nuts, grain with egg, and grain with cheese. Examples are a poached egg on toast, macaroni and cheese, and a tortilla with cheese.

(3) Beans, legumes (peas, lentils), rice or soybeans (tofu) with milk, nuts, or eggs.

d. Vegans should eat at least two of the following at the same meal in order to provide all essential amino acids:

(1) Grains or nuts and seeds.

(2) Dried beans or tofu.

(3) Wheat germ.

e. Whole-wheat grains and cereals are preferred in vegetarian diets. Other foods must be added to the protein sources to supply vitamins and minerals. Vegetarian diets are often deficient in calcium, iron, zinc, vitamin D, iodine, and riboflavin. Vitamin B12 is probably missing entirely. Supplements of these substances often need to be taken.

5-5. FACTORS WHICH ALTER A HOSPITALIZED PATIENT’S EATING PATTERNS

The meals served in a hospital cannot accommodate all social and cultural variations in food habits. However, meals can be individualized to assure that patients are provided with foods that are acceptable to them, but still within the restrictions of their diet. A meal, no matter how carefully planned, serves its purpose only if it is eaten. Many factors alter a patient’s eating patterns during hospitalization.

a. The forced menu of available foods.

b. Isolation from family and significant others.

c. Restriction in activity.

d. A forced eating schedule.

5-6. FACTORS IN ILLNESS WHICH MAY ALTER FOOD INTAKE

Nutrition plays an important part in a patient’s overall condition. A person who is ill may need help in meeting his basic needs for adequate nutrition. Certain factors in illness may alter food intake.

a. The disease processes. The patient’s ability to ingest food is dependent upon the condition of his mouth and oral structures, and his ability to swallow. Impairment of any of these components will interfere with eating.

b. Drug therapy, which may alter the patient’s appetite.

c. Anxiety about his illness.

d. Loneliness.

e. Diet restrictions. In many disease conditions, a special diet is an important part of therapy. In addition to educating the patient about the diet, you should help him to adapt to the diet and enjoy the food that he can have.

f. Changes in usual activity level. Exercise has been reported to increase, decrease, or have no effect on food intake. Although food intake is decreased immediately after exercise, habitual moderate exercise over a long period of time promotes increased food intake.

5-7. REASONS FOR HOSPITALIZED PATIENTS BEING AT RISK OF MALNUTRITION

a. The effect of the disease on metabolism. Most illnesses and diseases increase the need for nutrients. For example, one of the first symptoms of an infectious disease is loss of appetite and decreased tolerances for food. But, the infection and possible fever increase the metabolic rate and the actual nutrient requirements.

b. The disease may cause problems with absorption. An abnormality in either secretion or motility affects not only digestion but also optimal absorption. Motility is the movement of food through the digestive tract.

(1) Alterations in motility in the esophagus or stomach may result in symptoms of indigestion and vomiting. Increased motility of the gastric contents through the small and large intestines results in decreased absorption and diarrhea.

(2) Conditions that increase motility of the small intestine primarily affect absorption.

c. The anxiety and stress of being ill may reduce the patient’s appetite.

d. The treatment may cause problems with intake, digestion, or absorption. The decreased desire to eat may be caused by impaired ability to taste food because of medication, bloating resulting from decreased peristalsis in the gastrointestinal tract following surgery, or nausea resulting from chemotherapy. Withholding food for various tests and procedures, or restricting the patient’s intake may affect his appetite.

5.8. NURSING INTERVENTIONS WHICH HELP THE PATIENT MEET NUTRITIONAL NEEDS

Mealtime is an important event in the patient’s long day and the patient’s diet is an integral part of the total treatment plan. Certain nursing interventions may help the patient meet his or her nutritional needs.

a. Consider the patient’s food preferences as much as possible. Encourage the patient to fill out the selective menu, so that preferred foods will be served.

b. Provide the patient with assistance in selecting the appropriate foods from the menu. The use of selective menus has improved food acceptance in most hospitals.

c. Order and deliver the patient’s tray promptly when it has been delayed while he was undergoing tests or procedures.

d. Feed or assist the patient as necessary. Even patients, who can feed themselves, may need assistance in opening milk cartons, cutting meat, and spreading butter on bread.

e. Discuss the advantages of following the diet. Explain to the patient why he will feel better and heal faster. For some diseases or disorders, the patient may be required to follow a special diet during the period of illness or the remainder of his life.

(1) A high protein diet is essential to repair tissues in any condition, which involves healing, such as recovery from surgery or burns.

(2) A person with diabetes must adhere to a diet controlled in calories, carbohydrates, protein, and fat.

(3) A person with hypertension may require a diet restricted in sodium.

f. Inform the dietitian or food service specialist of any special needs the patient may have. A patient who has lost his teeth and has difficulty chewing will need modifications in the consistency of the food he eats.

g. Visit with the patient briefly when serving the food tray.

h. Encourage family members to visit during mealtime. If present, a family member may want to feed the patient who needs assistance. Be sure that this is relaxing and safe for the patient.

i. When conditions allow for it, encourage the ambulatory patient to go to the dining hall for meals or open curtains in a double room so that patients may eat together. If the patient must eat alone, turn on the television or radio.

5-9. RESPONSIBILITIES OF THE PRACTICAL NURSE IN RELATION TO DIET THERAPY

a. The practical nurse should be familiar with the diet prescription and its therapeutic purpose. Although individual trays are carefully checked before leaving the Nutrition Care Division, mistakes can happen. Examine each tray with the patient’s specific diet in mind. You should be able to recognize each type of diet.

b. You should relate the diet to body function and the condition being treated. For example, a low fat diet is usually the first step in treating patients with elevated blood lipids (hyperlipidemia). Hyperlipidemia may be caused by improper diet or it may have a secondary cause, such as hypothyroidism or renal failure. Untreated hyperlipidemia can lead to coronary heart disease.

c. Be able to explain the general principles of the diet to the patient, and obtain the patient’s cooperation.

(1) For example, teach a diabetic patient the relationship between his insulin and the amount of food consumed.

(2) Observe the patient’s reaction to the diet. If the patient understands the relationship between his condition and his diet, and is shown that he can continue to enjoy most of his favorite foods, he is more likely to remain on the diet.

d. Help plan for the patient’s continued care.

(1) Most patients are hospitalized only during the acute and early convalescent phases of their illness so it may be necessary to continue a special diet at home.

(2) Chronic conditions, such as diabetes or hypertension, require permanent dietary alterations.

(3) Be aware of the patient’s home situation and the problems that the diet may cause. The patient and his family will have to adjust their meal plans.

(4) Request a consultation for the patient with the dietitian early in the hospitalization to allow for instructions and follow-up care.

5-10. REASONS FOR THERAPEUTIC DIETS

Nutritional support is fundamental, whether the patient has an acute illness or faces chronic disease and its treatment. Frequently, it is the primary therapy in itself. The registered dietitian, along with the physician, carries the major responsibility for the patient’s nutritional care. The nurse, and other primary care practitioners provide essential support. Valid nutritional care must be planned on identified personal needs and goals of the individual patient. We should not lose sight of the reasons for therapeutic diets.

a. To Maintain or Improve Nutritional Status. The stereotypical all-American family with two parents and two children eating three balanced meals each day with a ban on snacks is no longer a common reality. Widespread societal changes include an increase in the number of women in the work force and families who rely on food items and cooking methods that save time, space, and labor. The “snack” is clearly a significant component of foods consumed. A therapeutic diet may be planned to promote foods that contribute to nutritional adequacy.

b. To Improve Nutritional Deficiencies. Dietary surveys have shown that approximately one third of the US population lives on diets with less than the optimal amounts of various nutrients. Such nutritionally deficient persons are limited in physical work capacity, immune system function, and mental activity. They lack the nutritional reserves to meet any added physiologic or metabolic demands from injury or illness, or to sustain fetal development during pregnancy.

c. To Maintain, Increase, or Decrease Body Weight. Despite the growing interest in physical fitness, one out of every four Americans is on a weight reduction diet. Only 5 percent of these dieters manage to maintain their weight at the new lower level after such a diet. The basic cause is an underlying energy imbalance: more energy intake as food than energy output as basal metabolic needs and physical activity. Being underweight is a less common problem in the US. It is usually associated with poor living conditions or long-term disease. Resistance to infection is lowered and strength is reduced. Other causes for a person being underweight are self-imposed eating disorders, malabsorption resulting from a diseased gastrointestinal tract, hyperthyroidism, and increased physical activity without a corresponding increase in food intake.

d. To Alleviate Stress to Certain Organs or to the Whole Body.

(1) When loss of teeth or dental problems make chewing difficult, a dental soft diet may be used. All foods are soft-cooked, meats are ground and sometimes mixed with gravy or sauces.

(2) Peptic ulcer is the general term given to an eroded mucosal lesion in the central portion of the gastrointestinal tract. Little is understood about its underlying causes. The prime objective in medical management is to provide psychologic rest and support tissue healing. Three factors form the basis of care: drug therapy, rest, and diet. The bland diets used in the past for treatment of peptic ulcer have proved to be ineffective. Positive individual needs and a flexible program of a regular diet, including good food sources of dietary fiber, milk, and other protein foods prevail today.

(3) General functional disorders of the intestine may be caused by irritation of the mucous membrane. Symptoms vary between constipation and diarrhea. Dietary measures are designed to provide optimal nutrition and regulate bowel motility. There should be additional amounts of fruits, vegetables, and whole grains. The fiber content may need to be decreased during periods of diarrhea or excessive flatulence.

(4) Organic diseases of the intestine fall into three general groups: anatomic changes, malabsorption syndromes, and inflammatory bowel disease with infectious mucosal changes.

(a) Diverticulosis is an example of anatomic changes. Current studies and clinical practice have demonstrated that diverticular disease is better managed with a high-fiber diet than with restricted amounts of fiber used in former practices.

(b) Celiac disease is an example of malabsorption syndrome. Since the discovery that the gliadin fraction in gluten (a protein found mainly in wheat) is the causative factor, a low-gluten, gliadin-free diet has resulted in marked remission of symptoms.

(c) Inflammatory bowel disease is a term applied to both ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease. These two diseases have similar clinical and pathologic features. They are particularly prevalent in industrialized areas of the world, suggesting that the environment plays a significant role. The two goals of a therapeutic diet are to support the tissue-healing process and prevent nutritional deficiency. The diet must supply about 100 grams of protein per day through elemental formulas or protein supplements with food as tolerated.

e. To Eliminate Food Substances to Which the Patient may be Allergic. There are three basic approaches to the diagnosis and treatment of food allergies: clinical assessment, laboratory tests, and dietary manipulation. Diet therapy is individualized.

f. To Adjust Diet Composition. A therapeutic diet may be ordered to aid digestion, metabolism, or excretion of certain nutrients or substances.

5-11. STANDARD HOSPITAL DIETS

The types of standard diets used by the Department of the Army are found in TM 8-500, Nutritional Support Handbook.

a. Clear Liquid Diet. This diet is indicated for the postoperative patient’s first feeding when it is necessary to fully ascertain return of gastrointestinal function. It may also be used during periods of acute illness, in cases of food intolerance, and to reduce colon fecal matter for diagnostic procedures.

(1) The diet is limited to fat-free broth or bouillon, flavored gelatin, water, fruit drinks without pulp, fruit ice, Popsicles®, tea, coffee or coffee substitutes, and sugar. No cream or creamers are used. Carbonated beverages may be included when ordered by the physician; however, they are often contraindicated.

(2) The standard menu mat (DA Form 2902-15R) provides approximately 1146 calories. This diet is below the recommended dietary allowances (RDA) for all nutrients tabulated except for Vitamin C (ascorbic acid). If the patient is to be on clear liquids for an extended period of time, the portion sizes should be increased or an accepted enteral formula may be provided.

b. Full Liquid Diet. This diet is used when a patient is unable to chew or swallow solid food because of extensive oral surgery, facial injuries, esophageal strictures, and carcinomas of the mouth and esophagus. It may be used to transition between a clear liquid and a regular diet for the post-surgical patient.

(1) The diet consists of foods, which are liquid at room or body temperature, and will easily flow through a straw. Included in the full liquid diet are all juices, strained soups, thinned, cooked cereals, custards, ice cream, sherbet, and milk. A high protein beverage is given at breakfast and between meals. Commercially prepared liquid supplements may also be used.

(2) The standard menu mat (DA Form 2902-12-R) provides approximately 2777 calories. This diet is slightly below the RDA in iron for females, and in niacin for men.

c. Advanced Full Liquid Diet. This diet may be prescribed to meet the nutritive requirements of a patient who must receive a full liquid diet for an extended period of time or who has undergone oral surgery and must have foods, which can pass through a straw.

(1) The foods permitted are the same as those allowed on the full liquid diet. The advanced full liquid diet is made more nutritious by the addition of blended, thinned, and strained meat, potatoes, and vegetables. High-protein beverages are served with meals and between meals.

(2) The standard menu mat provides approximately 4028 calories. The advanced full liquid diet meets the RDA for all nutrients tabulated.

d. Tonsillectomy and Adenoidectomy Cold Liquid Diet. This diet is used following a tonsillectomy and adenoidectomy (T&A). It is also used when only fluids or soothing foods in liquid form are tolerated.

(1) The T&A cold liquid diet provides only cold liquids, which are free of irritants or acid properties. Foods allowed are flavored gelatins, ice cream, sherbet, and milk. A high protein beverage is served between meals.

(2) The standard menu mat is DA Form 2902-14-R. The T&A cold liquid diet does not meet the RDA for niacin and Vitamin A for adult males or children ages 4 to 10, and is below the RDA for thiamine for children ages 1 to 4. It does not meet the RDA for iron for any age group.

e. Soft Diet. The soft diet is prescribed for patients unable to tolerate a regular diet. It is part of the progressive stages of diet therapy after surgery or during recovery from an acute illness.

(1) The diet consists of solid foods that are prepared without added black pepper, chili powder, or chili pepper. It does not contain whole grain cereals or salads with raw, fresh fruits and vegetables. Serving sizes are small to provide a gradual increase in the amount of food from the liquid diet.

(2) The standard menu mat (DA Form 2902-4-R) provides approximately 2236 calories. This diet does not meet the RDA in iron for females or thiamine for males, nor niacin for either males or females.

f. Dental Soft Diet. This diet is prescribed for patients who are recovering from extensive oral surgery, have severe gingivitis, have had multiple extractions, have chewing difficulties because of tooth loss or other oral condition, or for the very elderly, toothless patient.

(1) The diet is composed of seasoned ground meats, vegetables, and other foods, which are easily chewed. The individuality of the patient must not be overlooked when a dental soft diet is prescribed. Many patients resent being served ground meat.

(2) Standard menu mats available are DA Form 2902-6-R (dental soft diet) and DA Form 2906-13-R (dental soft, 2000 mg sodium diet). The dental soft diet does not meet the RDA in thiamin for males, nor iron for females.

g. Regular Diet. Regular diets are planned to meet the nutritional needs of adolescents, adults, and geriatric phases of the life span.

(1) The regular diet includes the basic food groups and a variety of foods. The basic food groups include meat, milk, vegetables, fruits, bread and cereal, fats, and sweets.

(2) The standard menu mat, DA Form 2901-R (Regular Diet) provides approximately 3375 calories. The selective menu is developed by each individual hospital according to patient needs, food availability, and cost. The regular diet is designed to provide exceptionally generous amounts of all recognized nutrients and meets or exceeds the RDA for all nutrients tabulated.

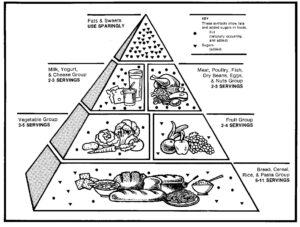

(3) The Food Guide Pyramid is an outline of what we should eat each day (see figure 5-1). It shows six food groups, but emphasizes foods from the five food groups shown in the lower sections of the Pyramid. You need food from each group for good health. Each of the food groups provides some of the nutrients you need. Food from one group cannot replace those of another group.

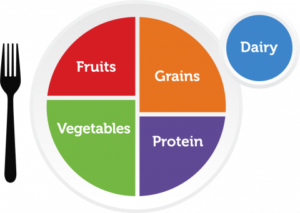

Note: Since the original publicateion of “Nursing Fundamentals II” the concept of a food pyramid has been changed. The US Department of Agriculture now promotes “MyPlate” as a better representation of what we should eat each day.

h. Diabetic Diet. The diabetic diet is indicated in the treatment of the metabolic disorder diabetes mellitus. This disease results from an inadequate production or utilization of insulin. The object of treating the diabetic patient by diet, with or without insulin or oral drugs, is to prevent hyperglycemia, hypoglycemia, glycosuria, and ketosis.

(1) The diabetic food exchange lists are the basis for a meal planning system that was designed by a committee of the American Diabetes Association and The American Dietetic Association. The system lists: meat exchange, bread exchange, fruit and juice exchange, vegetable exchange, milk exchange and fat exchange. The number of exchanges allowed is based upon the doctor’s order and the dietitian’s calculations. Each diabetic diet should be individualized to meet the needs of the patient. The foods in each exchange contain the same amount of calories, carbohydrate, protein, and fat per portion size. Patients select from the exchange based upon their preference.

(2) The adequacy and possible deficiencies depend on the calories. A diet of less than 1200 calories for women and less than 1500 calories for men would have a great chance of being deficient in some nutrients.

(3) The goals of the diabetic diet are:

(a) To improve the overall health of the patient by attaining and maintaining optimum nutrition.

(b) To attain and maintain an ideal body weight.

(c) To provide for the pregnant woman and her fetus: normal physical growth in the child, adequate nutrition for lactation needs if she chooses to breast-feed her infant.

(d) To maintain plasma glucose as near the normal physiologic range as possible.

(e) To prevent or delay the development and progression of cardiovascular, renal, retinal, neurologic, and other complications associated with diabetes.

(f) To modify the diet as necessary for complications of diabetes and for associated diseases.

i. Liberal Bland Diet. This diet is indicated for any medical condition requiring treatment for the reduction of gastric secretion, such as gastric or duodenal ulcers, gastritis, esophagitis, or hiatal hernia.

(1) The diet consists of any variety of regular foods and beverages, which are prepared or consumed without black pepper, chili powder, or chili pepper. Chocolate, coffee, tea, caffeine-containing products, and decaffeinated coffee are not included in the diet. The diet should be as liberal as possible and individualized to meet the needs of the patient. Foods, which cause the patient discomfort, should be avoided. Small, frequent feedings may be prescribed to lower the acidity of the gastric content and for the physical comfort of the patient.

(2) The standard menu mat, DA Form 2902-1-R, provides 3213 calories. The liberal bland diet is slightly below the RDA for thiamine and niacin for men 19 to 22 years of age. It is also below the RDA in iron for women of all ages.

j. Low Fat Diet. Fat restricted diets may be indicated in diseases of the liver, gallbladder, or pancreas in which disturbances of the digestion and absorption of fat may occur (pancreatitis, post-gastrointestinal surgery, cholelithiasis, and cystic fibrosis).

(1) The diet contains approximately 40 grams of fat from the six ounces of lean meat, fish, or poultry, one egg and three teaspoons of butter, margarine, or other allowed fats. Only lean, well-trimmed meats and skim milk are used. All foods are prepared without fat.

(2) The standard menu mat, DA Form 2905-R, provides approximately 2168 calories. Caloric content of the diet can be increased by adding allowable breads, vegetables, fruits, or skim milk. The diet is below the RDA in iron for males between the ages of 11 and 22 and females 11 through 50 years of age.

k. Sodium Restricted Diet. The purpose of the sodium-restricted diet is to promote loss of body fluids for patients who are unable to excrete the element normally because of a pathological condition. The diet is indicated for the prevention, control, and elimination of edema in congestive heart failure; cirrhosis of the liver with ascites; renal disease complicated by either edema or hypertension; when administration of adrenocorticotrophic hormone (ACTH) or steroids are prescribed, and for certain endocrine disorders such as Cushing’s disease and hypothyroidism.

(1) The sodium-restricted diets provide a specific sodium level or a range of sodium. The diet order must indicate the specific sodium level or range desired either in milligrams (mg) or mill equivalent (mEq). Terms such as “salt free” and “low sodium” are not sufficient.

(a) All foods on the 500 mg and 1000 mg sodium diets are prepared without the addition of salt, and foods high in sodium are omitted. The 500 mg sodium diet uses both sodium restricted bread and margarine. The 1000 mg sodium diet uses sodium restricted margarine and regular bread. The 2000 mg sodium diet uses regular bread and margarine, and regular cereal and desserts prepared with sodium.

(b) The standard menu mats, DA Form 2906-1-R (500 mg sodium diet), DA Form 2906-2-R (1000 mg sodium diet), and DA Form 2906-3-R (2000 mg sodium diet), provide between 2083 and 2554 calories.

(2) The diets are below the RDA in iron for males ages 11 to 22 and for females ages 11 to 50. Thiamine is inadequate for males at all levels. Calcium and niacin are also low for certain diets and ages.

5-12. PREPARING THE PATIENT FOR MEALS

a. As a nurse, your duties may include serving the diet trays at mealtime. For many patients, mealtime is the high point of the day. The patients are more apt to have a better appetite, eat more, and enjoy their food more if you prepare them for their meals before the trays arrive.

(1) Provide for elimination by offering the bedpan or urinal or assisting the patient to the bathroom.

(2) Assist the patient to wash hands and face as needed.

(3) Create an attractive and pleasant environment for eating. Remove distracting articles such as an emesis basin or a urinal, and use a deodorizer to remove unpleasant odors in the room. See that the room is well lighted and at a comfortable temperature.

(4) Position the patient for the meal. If allowed, elevate the head of the bed or assist the patient to sit up in a chair.

(5) Clear the overbed table to make room for the diet tray.

b. Avoid treatments such as enemas, dressings, and injections immediately before and after meals.

5-13. CLOSING

Helping patients meet their nutritional needs is a challenging task for a nurse. Ordering the tray and delivering it to the patient’s bedside is not enough. You must see that he eats the food needed to meet his body requirements. Provide the patient with assistance to complete selective menus that meet his food preferences as much as possible. See to his comfort at mealtime. Without proper nutrition, the healing process slows down and the patient’s condition does not improve as quickly as it should. You should always remember that the dietitians and hospital food service specialist (MOS 91M) of the hospital’s Nutrition Care Division are available to you as experts in all aspects of patient nutrition care. Ask for their advice or intervention when you believe a patient’s condition requires it.