Aviation Ear Nose and Throat Medicine |

DIAGNOSIS AND DISCUSSION: Perennial allergic rhinitis (PAR) and seasonal allergic rhinitis (SAR) are manifested by any or all of the following symptoms: rhinorrhea, sneezing, lacrimation, pruritus (nasal, ocular, and palatal) and congestion. Etiology is almost always due to inhaled allergens. SAR tends to be seasonal or multi-seasonal, such as from blooming plants, but PAR may be year round and is commonly caused by dust, molds, and animal dander. History alone is usually sufficient for a working diagnosis and initiation of treatment, but when symptoms are severe and/or persist in the face of treatment, further evaluation by an allergist or otolaryngologist is indicated. The presence of allergic nasal polyps greatly increases the chance of sinus barotrauma; the finding of polyps should be a cause for grounding and referral to ENT.

Allergic rhinitis may be mimicked by

Vasomotor Rhinitis, which may consist of rhinorrhea, sneezing, and congestion.

The congestion is often seen as alternating, sometimes severe, nasal

obstruction. Inciting factors include temperature and humidity changes, odors,

irritants, recumbency, and emotion. Treatment of vasomotor rhinitis with inhaled

nasal steroids can be effective, and, if symptoms aren't disabling, no waiver is

required The potential for VR to cause barotrauma is nil.

AEROMEDICAL CONCERNS: The following consequences of allergic rhinitis may interfere with aircrew duties: nasal airway compromise, nasal and facial pressure, the use of medications with unacceptable side effects, ear and sinus barotrauma with potential for in-flight incapacitation, and prolonged periods of grounding due to symptoms.

TREATMENT:

The first medications to consider in aircrew are those that don’t require a

waiver, namely inhaled nasal steroids and cromolyn (Nasalcrom), both of which

have negligible side effects. Topical

nasal steroid sprays can be highly effective, and in some cases even appear to

improve symptoms of allergic conjunctivitis.

Nasalcrom works best if taken before

symptoms occur, so it is more effective in persons who know when their

allergy season is about to begin.

Antihistamines can be very helpful, but

most have some sedating side effects and are therefore unacceptable for use in

members in a flying status. Two non-sedating antihistamines (Claritin and

Allegra) have been approved for use in flying personnel, with

a waiver. If one chooses to start an aircrew on one of these medications, a

seven-day grounding period is mandatory in order to observe for any untoward

effects. This period does not need to be repeated with subsequent use of that

particular drug, but if the member wants to try the other antihistamine, another

grounding period is necessary, as the two drugs are chemically dissimilar. A

one-time waiver request needs to be submitted to NAMI Physical Standards; the

chance of the waiver being granted is very good as long as the medication has

caused no untoward effects, and, of course, has proven to be effective. Only the

plain forms of these antihistamines are approved for Naval aircrew, not the ones

containing decongestants such as

pseudoephedrine.

Allergy immunotherapy (AIT) can be

highly effective and may even be considered curative, but is disqualifying for

aviation, although it is commonly waivered once the member is on a stable and

effective dose. AIT is difficult to administer (it has to be given for three to

five years, a 12 hour grounding period is necessary after each shot,

refrigeration is required, there can be a loss of serum potency, and

unpredictable difficulties may occur in obtaining refills).

It should not be undertaken if topical sprays or non-sedating

antihistamines are effective.

There has been success with an

accelerated method of reaching a maintenance dose (Rush technique), and, if

available, should be considered when grounding time must be minimized.

DIAGNOSIS

AND DISCUSSION: Acute

sinusitis (also known as acute bacterial rhinosinusitis) is the fifth most

common diagnosis for which an antibiotic is prescribed.

Between seven and twelve percent of all antibiotic prescriptions are for

this diagnosis. It usually occurs during or after an acute viral URI, and can be

assumed to be present if URI symptoms have not improved after ten days, or

worsen after five to seven days.

The American Academy of Otolaryngology feels that a bacterial infection is most likely if some or all of the following symptoms are prolonged or worsening: nasal drainage, nasal congestion, facial pain/pressure (especially if unilateral and localized anatomically to a particular sinus), postnasal drip, hyposmia/anosmia, fever, cough, fatigue, maxillary dental pain, and ear fullness/pressure. It is important to remember that most of these symptoms, including purulent anterior and posterior nasal drainage, are commonly seen in viral rhinosinusitis too. It is the prolongation and/or worsening of the symptoms that are most helpful in diagnosing a bacterial infection.

Although sinus x-rays can be helpful at times in making a diagnosis, they can’t differentiate between viral and bacterial mucosal thickening, so they’re generally unnecessary, especially within the first week of symptoms when the disease is almost always viral.

AEROMEDICAL

CONSIDERATIONS: Besides

the fact that the patient can be very symptomatic and therefore distracted from

his or her flying duties, the presence of nasal and sinus mucosal inflammation

causes edema which compromises free air flow in and out of the sinuses. This can

easily result in sinus barotrauma, which is occasionally so painful as to be

incapacitating. SCUBA divers know

they shouldn’t dive with sinusitis for the same reasons, but at least they can

turn around and head for the surface if they begin to feel sinus pain.

On the other hand, if a pilot starts to feel sinus pain on descending, he

or she must eventually descend all the way to the ground!

TREATMENT: The bacteria most responsible

are: S. pneumoniae, H. influenza, and M.

catarrhalis. Penicillin-resistant

strains of S. pneumoniae are becoming

more common; up to 28% are resistant in some areas of the country.

Up to 40% of H. influenzae strains inactivate beta-lactam antibiotics, and nearly

all M. catarrhalis strains produce

beta-lactamase. The reason for this high (and increasing) level of antibiotic

resistance is felt to be a result of two things: inappropriate prescribing of

antibiotics for uncomplicated viral rhinosinusitis, and prescribing of

ineffective antibiotics for bacterial rhinosinusitis.

There are three reasons for prescribing

antibiotics in bacterial rhinosinusitis: (1)

to get the sinuses healthy; (2) to prevent complications such as orbital

abscess, meningitis, or cerebral abscess; and, (3) to prevent chronic sinusitis.

The choice of antibiotics and their

dosages will depend on whether or not the patient has had an antibiotic within

the past four to six weeks, and whether their sinusitis is felt to be mild or

moderate. A “mild” case might be one in which the patient has had

purulent nasal drainage, congestion, and fatigue for 10 days. An infection might be classified as “moderate” if there

were also a low-grade fever and unilateral maxillary and upper tooth pain made

worse by bending over.

Recommended antibiotics are as follows:

Mild

symptoms and no recent antibiotic usage:

Amoxicillin/clavulanate

(Augmentin), amoxicillin, cefpodoxime proxetil (Vantin)

or cefuroxime axetil (Ceftin).

Failure

rates with other antibiotics, such at cefprozil (Cefzil), TMP/SMX

(Bactrim or Septra), doxycycline

(Vibramycin), azithromycin

(Zithromax) and clarithromycin

(Biaxin)

approach 25%; they are not among the recommended drugs.

Mild

symptoms with recent antibiotic usage, or moderate symptoms without recent

antibiotics: Augmentin in increased dosages such as 3 to 3.5 gm/day;

Vantin; or Ceftin. Patients allergic to beta-lactam antibiotics can be given

levofloxacin (Levaquin) or another newer quinilone.

Moderate

symptoms with recent antibiotic usage:

Levaquin or other newer quinilone;

Augmentin; or combination therapy such as

amoxicillin or clindamycin (Cleocin) for gram-positive organisms, and Vantin or

cefixime (Suprax) for gram negatives.

Failures: If there is no improvement in 72 hours, a switch of

antibiotics may be indicated, but the Academy has no firm guidelines, instead

advising that the new antibiotic choice should be based on “the likely

organism producing clinical failure”. In

any failure, an ENT evaluation for nasal endoscopy and possible culture is

appropriate, as is referral for a sinus CT.

Ancillary

treatment: Although antibiotics

are key in the treatment of acute bacterial rhinosinusitis, other treatments are

often used in addition. A

decongestant spray for up to three days may help in reducing mucosal edema,

especially when there is pain or significant pressure.

A mucus thinner such as guaifenesin may help improve mucus flow.

Topical nasal steroid sprays may reduce mucosal inflammation and promote

sinus ventilation and clearing. Saline

nasal spray or irrigation can help remove thick stagnant secretions.

There has been some controversy in the

literature about the need for any treatment at all in bacterial sinusitis, since

it is estimated that nearly 50% of patients will recover spontaneously without

treatment. However, the use of appropriate antibiotics will be effective in

nearly 90% of cases, thereby eliminating symptoms, reducing the risk of

complications, and nearly doing away with the likelihood that a given infection

will become chronic. If antibiotics

are reserved for those patients who are most likely to have a bacterial

infection, and the right antibiotic is used for the right length of time, there

should be no controversy. The

Academy of Otolaryngology doesn’t recommend how many days to continue

treatment, but a general consensus is that most antibiotics should be given for

at least seven days.

Mild sinusitis symptoms that persist for

12 or more weeks, with or without treatment, is considered chronic, and needs

ENT and radiologic evaluation in addition to a somewhat different choice of

antibiotics. Chronic sinusitis

frequently requires surgery, and its aeromedical ramifications are beyond the

scope of this guide. It should be

noted however that the diagnosis of chronic sinusitis is disqualifying for any

aircrew member, and a waiver is recommended only after the disease has been

eliminated medically and/or surgically.

DIAGNOSIS

AND DISCUSSION: This condition,

often called “swimmer’s ear” because of its association with water

immersion, is an infection of the skin of the ear canal.

It may be caused by either a fungus or a bacterium.

One of the common fungi causing O.E. is aspergillus;

a common bacterium is pseudomonas. The

classic presenting symptom is ear pain, which can be intensified by tugging on

the pinna, inserting an ear plug, or wearing a headset.

Purulent drainage is not a prominent symptom, although the ear canal may

be full of infected-appearing material. Pre-and

infra-auricular adenopathy is common, and occasionally there is visible swelling

of the pinna beyond the external canal. However, widespread pinna swelling

probably indicates perichondritis and the patient should be referred to ENT as

soon as possible, as loss of pinna cartilage can occur.

Healthy ear canals that are kept dry and

free of Q-tips almost never get infected, because a layer of cerumen over intact

skin is nearly impervious to invading organisms.

The ears most at risk are ones that are frequently Q-tipped or otherwise

manipulated by the patient in attempts to “clean” them. The manipulation not

only removes cerumen, it abrades the skin.

When water enters the warm, dark, vulnerable ear canal, an infection is

fairly likely, especially if the water stays in the canal for a while.

The use of acetic acid/alcohol drops after swimming can help prevent

infections by drying up the water and dropping the canal pH, thereby making the

area hostile to both fungi and bacteria.

AEROMEDICAL

IMPLICATIONS: the

combination of a painful, tender ear and reduced hearing may make flying,

especially while wearing a helmet or headset, extremely unpleasant.

And if there is drainage too, the ear cups can get messy. This can

distract aircrew from their duties.

TREATMENT: the key to treatment is to remove ear canal debris and

administer a topical antimicrobial. Cleaning

the ear canal can be difficult for two reasons: the canal may be swollen shut

making it difficult to see anything, and the canal may be so tender that the

patient won’t allow any manipulation with, say, a cerumen currette or suction

tip. Sometimes the canal can be

irrigated with an acidic solution, such as Domeboro, thereby removing some of

the semisolid material (a combination of exudate and squamous debris).

You can also firmly twist a piece of cotton into a wick and gently spin

it down into the canal. As it is removed, it takes some debris with it.

If the canal is at all swollen, just

giving the patient antibiotic drops may not help, as the drops won’t get down

into the canal. And any that do get in may just run out when the patient sits

up. The best way to administer the

drops is to first insert a wick in the canal. Most ENT physicians use a

compressed sponge wick, which is around 15 mm long and can be inserted into an

edematous canal rather deeply. The drops are then applied to the wick, which swells to fill

the canal. This allows for constant

contact of the antibiotic with the infected skin.

Once the wick is moistened, it is the patient’s job to keep it moist 24

hours a day. This is easy, as it

only takes a couple of drops every few hours to keep it wet.

This treatment is usually all that is

necessary, even if there are tender preauricular nodes and some mild edema of

the concha adjacent to the external canal.

The wick should be removed in approximately 48 hours, and a new one

placed if there is still any tenderness or obvious canal edema.

If the canal is open and no longer tender, have the patient use the drops

QID for another two or three days. They

should lie on their side and instill 4 to 6 drops deeply in the ear. The drops

may not go all the way in unless the patient pulls on the pinna, which allows

air trapped under the drops to escape. In

order to get some penetration, they should lie on their side for 5 minutes

before sitting up and allowing the excess drops to run out.

Once finished with the course of antibiotic drops, it might be a good

idea for the patient to use some acid/alcohol drops for a day, just to dry the

canal.

The preferred drops for a bacterial

infection? An aminoglycoside such

as Cortisporin suspension or Tobramycin. How

do you know if the infection is bacterial?

Generally, the more canal edema and tenderness, the more likely the

infection is to be bacterial. If

the canal is not tender or edematous, and the material in the canal looks thick

and almost curd-like, then fungus is more likely.

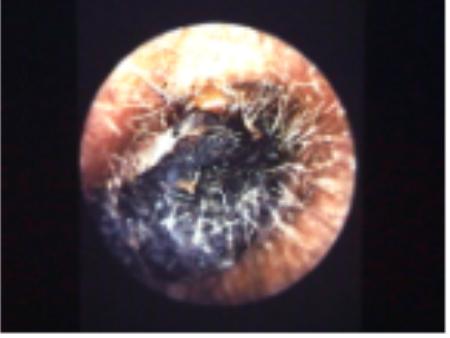

If you see a furry surface texture to the debris, and especially if you

see blackish discoloration, it is almost surely fungal.

You can then use a specific anti-fungal such as Lotrimin lotion, or any

of the acidifying drops, such as Vo-Sol. Just

as in bacterial otitis externa, treatment will be more effective if the canal is

cleaned as much as possible first. A

wick is probably not necessary if the canal isn’t edematous, but the patient

should still lie on his or her side for several minutes after using the drops.

In stubborn cases both types of drops can be alternated without a wick.

Once the infection has been successfully

treated, prevention of the next episode becomes important.

Warn your patient against putting anything in the ear for any reason. Tell them that wax is a good thing to have, and if too much

builds up you can help them. And if

they get water in the ear, especially pool water, they can reduce their chances

of getting reinfected by using acid/alcohol drops.

DIAGNOSIS

AND DISCUSSION: Most

eardrum perforations are traumatic. Some eardrums are more easily traumatized

than others. Previously perforated drums, or drums that have had p.e. tubes

placed in the past, may have thin spots that can easily rupture. And eardrums

scarred with big plaques of tympanosclerosis tend to heal slowly or not at all

when they are ruptured. The commonest causes for perforations seen in the

aviation population are mishaps in sports like diving and water skiing.

The usual mechanism is a sudden slap of water against the ear, which

pressurizes the air in the ear canal enough to instantly rupture the eardrum.

There have even been instances of perforation during water survival training

exercises, such as the tower jump and the helo dunker. Other causes include open

hand slaps, and welding slag burns.

Most perforations are painful when they

occur, but the pain may be minimal and short lived.

There may be a little blood in the ear canal, or none at all.

There may be a clear, yellowish discharge from the perforation

(especially if the perforation is contaminated with water, or the eardrum was

stretched badly before it ruptured). There

may be a noticeable hearing loss. But many perforations remain dry, and a

significant number have no associated subjective hearing loss. An easy way to

diagnose a perforation is to ask the patient to valsalva while you put your ear

near his or hers. If you hear the unmistakable sound of air escaping, there is a

perforation. A tympanogram will

give a perfectly flat tracing. And

an audiogram will possibly show a low-frequency conductive hearing loss.

Rarely, the trauma causing the

perforation may result in inner ear injury, which often means vertigo and/or a

sensorineural hearing loss. Direct trauma to the eardrum, such as from a Q-tip, can

dislocate the ossicles, and can actually force the stapes into the vestibule.

This causes instantaneous vertigo, and often a severe sensorineural loss as well

as the expected conductive loss. Such

cases should be referred to ENT as soon as possible.

AEROMEDICAL

IMPLICATIONS: By

itself, an uncomplicated eardrum perforation is compatible with flight, but is

technically disqualifying. The

hearing loss is rarely enough to interfere with communications in the aircraft,

and in the absence of vertigo it is usually fine to let the member continue to

fly. You should periodically check for healing, and if no

significant healing has occurred in three months, the patient should be referred

to ENT for surgical repair. Beware….sometimes

the perforation will appear to have healed, but what you’re actually seeing is

a layer of dead keratin covering the hole.

A valsalva will quickly reveal that there is still an opening, as will a

tympanogram.

If there has been a severe inner ear

injury with vertigo and/or marked nerve hearing loss, the member should be

grounded. In these cases the

prognosis is guarded, and if the stapes has been dislocated, the member is

grounded as if he or she had undergone a stapedectomy.

TREATMENT: Most uncomplicated perforations heal by themselves,

especially if all water is kept out and they remain uninfected. Some may begin to drain a thin serous fluid, which eventually

becomes purulent. These ears

require treatment with antibiotic drops, and Cortisporin suspension has been the

medication of choice for years. However,

there is increasing concern about putting an aminoglycoside in the middle ear,

so you should use FDA-approved Floxin (ofloxacin 0.3% otic solution) drops if

available. This concern is not based on the experience of thousands of ENT

physicians who have used aminoglycosides in perforations for many years, but it

is probably best to avoid aminoglycoside drops in a known or suspected

perforation, since the FDA now recommends only Floxin in these cases. Of course, because of the danger of

total inner ear destruction and even meningitis, the presence of pus

in a middle ear with an open labyrinth is an emergency deserving of immediate

ENT referral. If you can’t get

the patient seen immediately by ENT, you can use Floxin drops and consider

treating with a systemic antibiotic that will pass into the CSF.

DIAGNOSIS

AND DISCUSSION: The ears and

sinuses are susceptible to barotrauma whenever there is inflammation and edema

of the nasal passages, sinus ostia, and the eustachian tube orifices. This is

usually caused by an acute upper respiratory infection, and less commonly by

acute allergic rhinitis. Undiagnosed

sinusitis can cause multiple episodes of barotrauma.

Generally, barotrauma occurs on descent. This can happen in an aircraft, while SCUBA diving….or even while making a rapid descent in a skyscraper elevator! The problem is the vacuum that results when air fails to re-enter a body cavity (sinus or middle ear in this case) during a drop in altitude. The vacuum will pull the eardrum inward, causing pain, effusion, and even bleeding into the middle ear. Since the sinuses don’t have stretchable walls, they respond to the vacuum by rapidly forming a submucosal hematoma. Both ear and sinus barotrauma can be exquisitely painful. Fortunately for aircrew, the pressures involved rarely cause eardrum perforations. Initially, the diagnosis is made by history, and your examination helps confirm it.

Ear barotrauma can result in a reddened,

retracted eardrum, often with visibly bloody fluid in the middle ear. Bubbles

are often seen in the fluid when specifically looked for.

A tympanogram, if available, will show either a negatively displaced

peak, or a shallow, flattened curve.

Sinus barotrauma is usually so painful

and so localized that history alone can make the diagnosis. A set of plain sinus

films will often show a hematoma at the site of the pain, and sinus mucosal

thickening from the URI or sinusitis that caused the barotrauma.

Repeat films in two to three weeks can be helpful in deciding when a

member can resume flying.

AEROMEDICAL

IMPLICATIONS: The pain of barotrauma can be so great that it is almost

impossible to focus on the mission. Isolated

episodes of barotrauma are not disqualifying but repeated barotrauma not

obviously caused by, say, a URI, can result in permanent grounding, although

in most cases a cause is found and fixed. Chronic

sinusitis and nasal polyps are often the culprits, and are responsive to medical

and surgical treatment. These diagnoses are disqualifying, requiring a waiver

once they’ve been successfully treated.

TREATMENT: Most cases of ear barotrauma don’t require treatment, as

the middle ear effusion usually clears spontaneously in three to seven days.

Adding decongestant sprays and pills hasn’t been shown to have much

effect. If an effusion persists for

more than a week, there is usually more than a URI at the root of the problem,

and the next step is to obtain a thorough ENT examination.

Sinus barotrauma may be due to a URI,

and also doesn’t require treatment unless there is persistent pain or pressure

over the blocked sinus. A

decongestant spray given acutely may relieve the vacuum, and no further

treatment may be necessary. However,

if sinus films have been taken and show evidence of sinusitis, the patient needs

antibiotic treatment followed by evidence of subsequent clearing on X-ray before

going back to flying. If only a

hematoma is seen on X-ray, and the patient admits to trying to fly with a cold,

he or she could be returned to flying once all URI symptoms have resolved.

Follow-up X-rays aren’t mandatory in such a case.

Repeat sinus films may show that a

hematoma is apparently enlarging, but in reality it probably enlarged acutely,

right after the first films were taken, and is now starting to shrink.

It is not necessary to demonstrate that a hematoma has resolved before

letting the patient fly. It is the

underlying cause that must have resolved, not the hematoma itself, because

hematomas rarely interfere with sinus function.

DIAGNOSIS

AND DISCUSSION: The

diagnosis of nosebleed is easy, but what may be more difficult is finding the

cause and the exact site of bleeding. Bleeding

from the anterior nasal septum, which is well supplied with blood vessels, is

common. It is usually caused by excessive mucosal drying from

breathing low-humidity air. The dry

mucosa tends to crust, and when it’s manipulated it bleeds.

This manipulation is known in the vernacular as “nose picking”, and

it doesn’t require dry mucosa in order to cause bleeding!

Anterior epistaxis is rarely caused by

tumors, clotting disorders, or a-v malformations, so someone with an occasional

episode shouldn’t need an extensive evaluation.

Anterior bleeds are relatively innocuous.

Posterior epistaxis is far more serious.

The blood loss can be quite rapid, and can even result in shock.

The bleeding vessel is often a branch of the sphenopalatine or ethmoidal

arteries, and the vessel itself may be diseased and unable to contract.

Persons with posterior bleeds often have other health problems such as

hypertension, cardiovascular disease, and alcoholism.

Their care, in addition to stopping the bleeding, should eventually

include a thorough history and physical plus lab studies and a hematologic

evaluation. Consider hospital

admission even if you have stopped the bleeding.

AEROMEDICAL

IMPLICATIONS: An anterior nosebleed while flying can be a nuisance and

therefore a distraction. A

posterior nosebleed while flying can be life threatening.

Not only would it be very distracting, it is possible for the member to

become syncopal and even aspirate a significant amount of blood.

Anterior nosebleeds can almost always be treated successfully without

need for grounding. Posterior nosebleeds are fortunately very rare in the active

duty flying population, but would be a cause for grounding until the patient is

thoroughly evaluated and the chance of recurrence is felt to be low.

TREATMENT:

For anterior bleeds, treatment is fairly easy.

The most basic treatment is to blow out any clots and pinch the nostrils

shut for five or ten minutes. If

the bleeding quickly returns, placing a cotton pledget (moistened with a

decongestant spray such as Afrin) into the nostril, then pinching for five

minutes will often work. If that

fails, and you can definitely see the bleeding site, try applying a silver

nitrate stick. Firmly press it on

the precise bleeding spot and hold it for 30 seconds.

After the bleeding has stopped, you can put a small amount of antibiotic

ointment on the cauterized area, cover it with a piece of dry cotton, and tell

the patient to avoid any manipulation, including simple nose rubbing, for 48

hours. If it continues to bleed,

the patient will probably need a tight anterior pack of something like Vaseline

gauze. If an electrocautery is

available, the bleeding site can be cauterized, although this sometimes creates

a hard eschar that will bleed when it separates, especially if it is picked off

by the patient.

Posterior bleeds tend to come on without

warning or obvious precipitating factors, although they occasionally occur in

alcoholics during drinking episodes. The amount of bleeding can be frightening

for the patient and the health care provider alike, and stopping it can take

near-heroic measures. Various

treatments are used in Emergency Departments, ranging from placing a compressed

Merocel sponge into the bleeding nostril to using a foley catheter as a

posterior pack. Initially, all

treatments seem to work, because the bleeding can stop spontaneously after 15

minutes or so. This pause in the

bleeding has convinced many a provider to send the patient home without a pack.

They almost always return.

If the bleeding has stopped by the time

you see the patient, you can surmise that the source was posterior if: 1) the

blood loss was large, and 2) the patient claims to have swallowed a lot of it.

Unless the patient can get back to you very quickly if bleeding resumes,

it may be best to pack the nose even if there is no bleeding. Packing only makes sense if you know from which side the

bleeding originated, and in posterior bleeds this may not be obvious because

blood that flows into the nasopharynx can come back out both nostrils.

However the patient can usually tell you which nostril first showed

blood.

Assuming that you have no sophisticated

equipment, the quickest way to stop a posterior bleed is to put a foley catheter

in the bleeding nostril, look for the tip to appear behind the soft palate, and

fill the balloon with 8-10 ccs of water. Pull

the catheter towards you until the balloon seals the back of the nose and blood

stops flowing down the back of the throat.

While holding tension on the catheter, pack the nostril very firmly with

Vaseline strip gauze until all anterior bleeding is stopped.

Since tension must be maintained on the catheter, you have to find a

clamp (an umbilical clamp is ideal) and clamp the catheter under tension close

to the nostril. Be sure to put some padding between the clamp and the nostril. You

can use several layers of gauze or a piece of foam rubber, but if you use

nothing, the pressure of the clamp on the nostril skin will cause necrosis and

eventual notching.

If you have the time and the proper

supplies, this unpleasant procedure can be made much more tolerable for the

patient. Ideally you want all the

clots blown out, the nostrils sprayed with Afrin or Neo-Synephrine, cotton

pledgets soaked with a topical anesthetic placed in the bleeding nostril (3-5%

cocaine, if available, works well), and even a sedative administered.

These patients should have an IV. Blood can then be drawn for typing,

crossmatching and baseline H&H, and oxygen administered by mask when

feasible. But if you’ve got

nothing except a foley, a syringe, some water, a packet of vaseline gauze, and a

mosquito clamp, you can save this patient. You can then start looking for the

cause of the bleed at a more leisurely pace.

AEROMEDICAL

IMPLICATIONS: As

for any acute illness, the member with pharyngitis or tonsillitis should be

grounded until symptoms have resolved. Eustachian tube dysfunction is very

common with pharyngitis. Although it indicates a more severe condition, a

history of peritonsillar abscess is not disqualifying. TREATMENT: Antibiotics are generally reserved for cases of pharyngitis

in which there is significant fever, and exudates are present.

Treatment is optional if there are exudates in a patient with normal

temperature. If available, a rapid

strep screen may be helpful in deciding which patients will need antibiotics.

If the patient has exudative tonsillitis, even with a negative DIAGNOSIS

AND DISCUSSION: In

the aviation world, vertigo means spatial disorientation.

In the medical world it means, essentially, a “hallucination of

motion”, generally a spinning or falling sensation. Aviator’s vertigo may be a transient

phenomenon having to do with abnormal perceptions of normal physiologic

responses. A pilot who is flying on

a dark night may lose visual cues and begin to rely on inner ear cues instead.

These cues may well be at odds with what the instruments are indicating,

and the feeling of disorientation can be so strong that the pilot wrongly sides

with the ears and makes improper control inputs.

The result is usually a crash. True

vertigo, which is often manifested by a sensation of spinning, can occur

anywhere and at any time, and is not a phenomenon of flight.

The subject of vertigo can fill a large book and won’t be discussed in

great detail here, but as a rule a patient suffering from inner ear vertigo will

have visible nystagmus and some very unpleasant autonomic signs and symptoms

such as sweating, nausea, vomiting, and tachycardia. There may or may not be

worsening with certain head motions or static positions, and there may or may

not be accompanying unilateral ear symptoms such as tinnitus, pressure, and

hearing loss (as in Meniere’s disease). When taking a history, you should also

ask about other neurologic symptoms, since true vertigo may also have a

cerebellar or brainstem etiology. Ask about recent head trauma. True vertigo in

an aircrew must be thoroughly evaluated before there is any likelihood of

returning to flying. AEROMEDICAL

IMPLICATIONS: True

vertigo is a cause for immediate grounding. Meniere’s disease is a condition

that by definition results in recurrent episodes of vertigo, and is not

waiverable until treatment (medical or surgical) has been shown to be 100%

effective for at least a year. Once a definite diagnosis of Meniere’s disease

is made, Naval Aviators will not receive a waiver to fly solo, although they may

be waived to fly dual-controlled aircraft as long they are accompanied by an

unrestricted pilot who is fully qualified in that aircraft. Other types of vertigo, particularly

those that are unlikely to recur, may be waived. Two examples would be

vestibular neuronitis and benign positional vertigo. Vestibular neuronitis is

unlikely to recur, and benign positional vertigo patients can be allowed to fly

once the attacks have subsided and cannot be provoked by any type of head motion

for a period of at least two weeks. Benign positional vertigo may recur years

later, but most recurrences happen early in the morning when the patient rolls

over in bed or gets up out of bed, not in the middle of the day while flying. TREATMENT:

Most treatment in an

operational setting would be limited to relief of symptoms.

Acute spinning vertigo may bring on vomiting, which can be treated with

labyrinthine sedatives such as parenteral benzodiazepines.

Phenergan IM or suppository may also help. IV hydration may be necessary.

Avoidance of provocative head positions

for a day or two can partially alleviate acute symptoms.

Be alert to other neurologic signs and symptoms that may indicate the

presence of a cerebrovascular accident. There are even cases in the literature

of acute vertigo caused by therapeutic neck manipulation resulting in dissection

of a vertebral artery and rapid cerebellar infarction. There is a treatment for benign

positional vertigo that can have a nearly immediate effect, and that is the

canallith repositioning (Epley) maneuver. BPV

is characterized by reproducible positionally-related episodes of vertigo that

come on a few seconds after the provocative head movement is performed (known as

“latency”), the episodes are accompanied by crescendo-decrescendo rotary

nystagmus (either clockwise or counter-clockwise), and which tend to become less

severe with each repetition (fatigability). The Epley maneuver is somewhat

complicated, but directions can be found in standard ENT and Neurology texts.

Anyone can perform it, and in many cases it resolves all symptoms after a

single application. Definitive treatment for Meniere’s

disease can involve the use of long-term medications and/or surgery, both of

which are covered well in standard ENT texts and are out of the realm of

operational medical care. AEROMEDICAL

IMPLICATIONS: Although cerumen can cause hearing loss, it usually isn’t a

problem in aircraft because the aircrew can increase the radio and intercom

volume to compensate. The main problem is pain, and it may come from the

external pressure of wearing a helmet or headset. But the most significant pain may come from inserting an ear

plug into an already occluded ear canal. The cerumen can be pushed into contact

with the tympanic membrane, causing pain whenever the eardrum moves laterally

(such as during valsalva) or the impaction itself moves (such as during

yawning). TREATMENT: If you have the right instruments, such as an open-ended

otoscope with a relatively large speculum, plus a metal cerumen curette, you can

often remove the impaction mechanically by rolling it out. Always take care to avoid traumatizing the bony inner

two-thirds of the ear canal. Even

the slightest touch of the curette on this vulnerable skin will cause pain, and

bleeding lacerations are fairly common. If

the right tools and skills aren’t available, it is best to use softening drops

such as Debrox for a few days, then try to irrigate. Irrigation with a 20cc syringe full of warm water attached to

a #14 angiocath (minus the needle) will often get results.

Water-Piks have been used successfully too.

A riskier method is to use the big stainless steel syringe made for this

purpose. Risky because it is possible to wedge it in the ear canal and cause a

hydraulic rupture of the eardrum. But

when used correctly, this syringe can put out a voluminous stream of water and

completely remove the impaction with one filling.

As a rule, it is best to aim the stream superiorly, because many

impactions settle and leave a small opening above.

The water can enter through this breach and help push the wax laterally. Be careful to avoid entering the ear canal itself; you risk

bruising or tearing the fragile skin with the tip of the syringe, or even

rupturing the eardrum. This section was contributed by CDR Jay Phelan, MC, USN (FS). Bureau of Medicine and

Surgery Operational

Medicine Home

· Military

Medicine · Sick Call

· Basic Exams ·

Medical Procedures

· Lab and X-ray ·

The Pharmacy ·

The Library ·

Equipment ·

Patient Transport

· Medical Force

Protection ·

Operational Safety · Operational

Settings ·

Special

Operations ·

Humanitarian

Missions ·

Instructions/Orders ·

Other Agencies ·

Video Gallery ·

Phone Consultation

· Forms ·

Web Links ·

Acknowledgements ·

Help ·

Feedback · This web version is brought to you

by The Brookside Associates Medical Education

Division · Other

Brookside Products ·

Contact Us

Department of the Navy

2300 E Street NW

Washington, D.C

20372-5300

Health Care in Military Settings

CAPT Michael John Hughey, MC, USNR

NAVMED P-5139

January 1, 2001United States Special Operations Command

7701 Tampa Point Blvd.

MacDill AFB, Florida

33621-5323