1-4. COMPLETE AND INCOMPLETE FRACTURES

A fracture occurs when a bone is broken. The break may only be a crack in the bone (incomplete fracture) or the bone may be broken into two separate parts (complete fracture). Any fracture can be serious. A fracture of a large bone like the femur can result in a significant loss of blood that, in turn, can result in hypovolemic shock. Complete fractures are also dangerous because the sharp ends of the fractured bone can injure muscle tissues, nerves, and blood vessels. If a rib is fractured in two places, the bone segment between the two fractures may “float” and damage an organ (such as the heart or a lung) or a major blood vessel (such as the aorta).

1-5. CLOSED AND OPEN FRACTURES

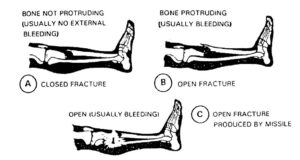

a. Closed Fracture. A closed fracture (see figure 1-3A) is a fracture in which the skin is not broken. A closed fracture may result in significant loss of blood due to internal bleeding (bleeding into surrounding body tissues or into a body cavity). This blood loss may result in shock.

b. Open Fracture. An open fracture is one in which the skin is broken (penetrated). The source of the penetration may have been the end of a fractured bone (see figure 1-3B) or a foreign object, such as a bullet, which penetrated the skin and fractured the bone (see figure 1-3C). If an open wound is caused by a fractured bone, the bone may remain visible or it may slip back below the skin and muscle tissues. An open fracture usually results in more blood loss than does a closed fracture since the blood can escape through the open wound. There is a risk of shock from blood loss. Infection is also a major concern since the skin is broken.

1-6. COMMON CAUSES OF FRACTURES

Fractures may be caused by a direct blow to the body (such as being hit by a vehicle) or by indirect force that results in a fracture away from the point of impact (such as a hip fracture resulting from a person landing on his knee after a hard fall). A fracture can also result from a limb being twisted (fracture and dislocation may result) or from powerful muscle contractions (such as may occur during a seizure). Fatigue (stress) fractures can result by repeated stress, such as a stress fracture of the foot during a long march. Certain diseases, such as cancer, can weaken bones and make them easier to break. High-energy impacts, such as being hit by a speeding vehicle or by a bullet, may produce multiple fractures and cause severe damage to surrounding tissues.

1-7. TYPES OF FRACTURES

A fracture may be displaced (bone moved out of normal alignment) or nondisplaced (bone remains in normal alignment). A nondisplaced fracture may be difficult to identify without an x-ray. Therefore, anytime you suspect that a fracture may be present, treat the injury as though you knew the fracture existed. Some types of fractures are briefly described in the following paragraphs.

a. Greenstick. A greenstick fracture is an incomplete fracture in which one side of the bone is broken and the bone is bent.

b. Comminuted. A comminuted fracture is one in which the bone is crushed or splintered into many pieces.

c. Transverse. A transverse fracture is a straight crosswise fracture (break is at a right angle to the axis of the bone).

d. Oblique. An oblique fracture is a diagonal or slanted fracture (not at a right angle to the axis of the bone).

e. Spiral. A spiral fracture coils around the bone and is caused by twisting.

f. Impacted. An impacted fracture results when one bone is driven into another bone, resulting in one or both bones being fractured and the bones being wedged together.

g. Pathologic. A pathologic fracture results when a bone that has been weakened by disease breaks under a force that would not fracture a normal bone.

h. Epiphyseal. An epiphyseal fracture is a fracture located between the expanded end of a long bone (epiphysis) and the shaft of the bone.

1-8. SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS OF FRACTURES

A fracture may be found during the primary or secondary survey of the casualty. Life-threatening injuries (lack of breathing, massive bleeding, and shock) should be treated before fractures since they immediately threaten a casualty’s life. A serious fracture, however, can also be life threatening. A fracture can be identified by the following signs and symptoms.

NOTE: A sign is something that can be observed by someone other than the casualty. Bleeding, bruises, and pulse rates are examples of signs. A symptom is something which the casualty senses, but which cannot be observed directly by another person. Pain is an example of a symptom.

a. Visible Fracture. In an open fracture, the fractured bone or bone fragments may be visible.

b. Deformity. The body part may appear deformed due to the displacement of the bone, the unnatural position of the casualty, or angulation where there is no joint (for example, the casualty’s forearm is “bent” instead of straight).

c. Pain. The casualty will probably experience pain at a particular location. The pain (point tenderness) usually identifies the location of the fracture. The casualty may be able to “feel” the fractured bones.

d. Swelling. There may be swelling (edema) at the suspected fracture site.

e. Discoloration. The area around the suspected fracture site may be bruised or have hemorrhagic spots (ecchymosis).

f. Crepitation. The fracture bones may make a crackling sound (crepitation) if they rub together when the casualty moves.

CAUTION: Do not ask the casualty to move the injured body part in order to test for crepitation.

g. Loss of Motion. The casualty may not be able to move the injured limb. If a spinal injury is present, paralysis may exist, especially paralysis of the legs.

h. Loss of Pulse. If the fractured bone is interfering with blood circulation, there may be no pulse distal to (below) the site of the fracture.

i. False Motion. There may be motion at a point where there is normally no motion. This movement at the fracture site is called false motion.

1-9. GENERAL PRINCIPLES FOR TREATING FRACTURES

Fractures may be discovered either during the primary or secondary survey of the casualty. Take measures to maintain or restore breathing and heartbeat, control major bleeding, and control shock before treating a fracture. The general procedures for treating a fracture of an extremity (arm or leg) are given below.

NOTE: Procedures for restoring breathing and heartbeat are given in Subcourse MD0532, Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation. Procedures for controlling external and internal bleeding and controlling shock are given in Subcourse MD0554, Treating Wounds in the Field. Procedures for treating a spinal fracture are given in Lesson 2 of this subcourse.

CAUTION: Do not move the casualty before splinting the fracture unless you must remove the casualty (and yourself) from immediate danger (escape from a burning vehicle, move out of the line of fire, and so forth).

a. Reassure Casualty. Tell the casualty that you will take care of him.

b. Expose the Limb. If you suspect the casualty has a fractured limb, gently remove the casualty’s clothing from the injured limb and check for signs of a fracture. Loosen any clothing that is tight or binds the casualty. DO NOT remove the casualty’s boots.

CAUTION: Do not expose the limb if you are in a chemical environment (chemical agents are present and the “all clear” signal has not been given).

c. Locate Site of Fracture. The site of the fracture is normally found by identifying the site of the deformity, false motion, bruise, wound, and/or point tenderness. To determine point tenderness in a conscious casualty, gently palpate the area with your fingers to determine the location of maximum discomfort.

d. Remove Jewelry, If Appropriate. If the casualty has a suspected fracture of the arm, remove any jewelry on the injured arm and put the jewelry in the casualty’s pocket. If the limb swells, the jewelry may interfere with blood circulation. The jewelry may then have to be cut off to restore adequate blood circulation.

e. Assess Distal Neurovascular Function. Check for impairment of the nerves and/or circulatory system below the site of the suspected fracture. Some of the methods used to identify impairment are given below.

(1) Check pulse. Palpate a pulse site below the fracture site. If no pulse or a weak pulse is found, the fracture may be putting pressure on the artery or may have damaged the artery. A weak pulse can be determined by comparing the pulse felt below the fracture with the pulse felt at the same location on the uninjured limb. A casualty with no pulse below the fracture site should be evacuated as soon as the limb is splinted.

(2) Check capillary refill. If the fractured limb is an arm, press on the casualty’s fingernail, then release. If normal color does not return within two seconds, the limb may have impaired circulation. This is also called the blanch test.

(3) Check skin temperature. Touch the casualty’s skin below the fracture. Coolness may indicate decreased or inadequate circulation. Compare the temperature of the injured limb to the temperature of the same area on the uninjured limb.

(4) Check sensation. Ask a conscious casualty if he can feel your touch. Then lightly touch an area below the fracture. For example, if his arm is fractured, touch the tip of the index and little fingers on the injured arm. Ask the casualty if the injured limb feels numb or has a tingling sensation.

(5) Check motor function. Ask a conscious casualty to try opening and closing the hand of an injured arm or moving the foot of an injured leg. If the attempt produces pain, have the casualty stop his efforts.

f. Dress Wounds. If the fracture is open, apply a field dressing or improvised dressing the wound before splinting the limb. Do not attempt to push exposed bone back beneath the skin. If the bone slips back spontaneously, make a notation of the fact on the casualty’s U.S. Field Medical Card (FMC). The card is initiated after treatment is completed and accompanies the casualty to the medical treatment facility.

g. Immobilize Fracture. Immobilize the fracture to relieve pain and to prevent additional damage to tissues at the fracture site due to movement of the fractured bone(s). If an extremity is fractured, apply a splint using the following general rules.

CAUTION: The general principle is “splint the fracture as it lies.” Do not reposition the fracture limb unless it is severely angulated and it is necessary to straighten the limb so it can be incorporated into the splint. If needed, straighten the limb with a gentle pull.

(1) If the fracture site is not on a joint, immobilize the joint above the fracture site and the joint below the fracture site.

(2) If a joint is fractured, apply the splint to the bone above the joint and to the bone below the joint so the joint is immobilized.

(3) Pad the splint at the joints and at sensitive areas to prevent local pressure.

(4) Minimize movement of the limb until it has been splinted.

(a) If the shaft of a long bone is fractured and severely deformed, apply gentle manual traction to attempt to align the limb so it can be splinted.

(b) If resistance is encountered when manual traction is applied, stop your efforts and splint the limb in the position of deformity.

NOTE: If the femur is fractured, a traction splint is available, and sufficient personnel are available, apply the traction splint to the leg using the procedures given in Lesson 3 of this subcourse.

(5) Secure the splint above and below the fracture site.

(a) Recheck the pulse below the securing device (cravat, strap, or other material) each time a securing device is applied. If the device interferes with blood circulation, loosen and retie the securing material.

(b) Never apply a cravat or other securing material directly over the fracture site.

(6) If you are in doubt as to whether an extremity does or does not have a fracture, splint the extremity.

h. Check Distal Neurovascular Function. Check again for impairment of the nerves and/or circulatory system below the site of the fracture using the procedures listed in paragraph e on the previous page.

i. Evacuate the Casualty. Evacuate the casualty to a medical treatment facility. If you cannot detect a pulse below the fracture site, evacuate the casualty as soon as possible in an effort to save the limb.

1-10. SPLINTS

A splint is a device that immobilizes part of the casualty’s body. Applying a splint to the injury helps to relieve pain and prevent further damage by minimizing movement. Splints are used to immobilize fractured bones, but they are also used to immobilize limbs with dislocations, sprains, and serious soft tissue injury. A splint may be a special device or a splint may be improvised. Some types of splints are briefly discussed below.

a. Traction Splint. A traction splint holds a fracture or dislocation of an extremity (usually a fracture of the femur) immobile and provides a steady pull (traction) to the extremity. The traction acts to align the fractured bone and protect the tissues surrounding the fracture site.

b. Pneumatic Splint. A pneumatic (air) splint is a cylinder made of double-walled, heavy-duty, clear plastic. The injured limb is placed inside the cylinder; then the cylinder is inflated to make the splint rigid. The splint immobilizes the fracture and provides pressure to the injured limb that helps control external and internal bleeding.

c. Wire Ladder Splint. A wire ladder splint is made of strong, lightweight wire that can be bent by hand to fit various shapes.

d. SAM Splint. The SAM (universal) splint consists of a sheet of aluminum with a foam covering. The splint can be bent by hand to fit various shapes.

e. Anatomical Splint. An anatomical splint exists when one part of the casualty’s body is used to immobilize an injured part of the body. For example, a casualty’s injured leg can be tied (secured) to his uninjured leg.

f. Improvised Splint. An improvised splint is made of one or more rigid objects that are secured to the injured limb with available materials. Boards, poles, tree limbs, rolled newspaper, and unloaded rifles are examples of materials that can be used as rigid objects. Bandages, strips of cloth torn from a shirt, and belts are some examples of securing materials.