Bob Blizzard was Tom’s classmate and friend in Greenville.

He writes about Bob in his letter to Zoe on January 10, 1941:

Bobs [1]Bob Blizzard, Tom’s friendtrying to fall in love again this time with Shirley Ward he sort of held back because he thought she was too young but Bill B. and Baker seemed to do O.K., so he has decided to try.

This pursuit was not successful as Shirley later married another man.

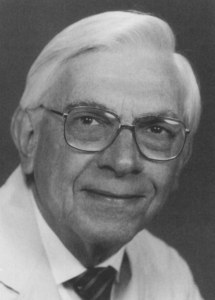

Bob served in an Army medical unit during WWII. After the war, he went on to attend Northwestern University Medical School. After graduating, he became a pediatric endocrinologist, teacher and researcher. He was later recognized by the Endocrine Society with this citation:

Citation for the Robert H. Williams Distinguished Leadership Award of The Endocrine Society to Robert M. Blizzard

The Endocrine Society is proud to honor Robert M. Blizzard, M.D., with its 1994 Robert H. Williams Distinguished Leadership Award, given annually by the Society to a member who has served the field of endocrinology and has nurtured generations of endocrinological scholars.

Bob Blizzard was born and grew up in Illinois farm country. With the exception of 3 years in the U.S. Army, Bob spent the formative years of his life in Illinois and Iowa—in high school in Greenville, IL, at Northwestern University and Medical School, and at the Raymond Blank Memorial Hospital in Des Moines. Bob is proud of his Midwestern heritage—a heritage which probably accounts for so many of his endearing attributes: persistence, patience, integrity, honor, and devotion to friends and family.

When Bob’s remarkable career is viewed in its entirety— at least thus far, because there will no doubt be additional contributions—one is struck by its remarkable breadth and depth. In the first phase, we meet Bob Blizzard the researcher and teacher of pediatric endocrinologists. Studying pediatric endocrinology at Johns Hopkins under Lawson Wilkins and in the company of others destined to become leaders in endocrinology, including Claude Migeon, Melvin Grumbach, Alfred Bongiovanni, and Judson VanWyk, was an invigorating experience.

After 3 years on the faculty at Ohio State University, Bob returned to Johns Hopkins when Wilkins retired as chief of the Division of Pediatric Endocrinology. During the Hopkins years from 1960-1974, working with Claude Migeon, Bob trained the “Wilkins grandchildren.” They came to Hopkins from all over the world, and they now populate academia and corporate research organizations as professors, division chiefs, department chairpersons, deans, and vice presidents.

His own research during the Hopkins years was both diverse and extensive in scope. He is a recognized authority on the relationship of immune disorders to endocrine disease, including the thyroid and adrenal glands, as well as insulin-dependent diabetes mellitus. What sets Bob Blizzard’s career apart from many others is his ability to see a challenge or an unmet need, whether in research, medical education, or public policy, and to take definitive and responsive action.

During those years at Hopkins, he recognized that GH deficiency would never be a treatable disorder unless the supply of hGH was increased and controlled in a rational way. Working with the NIH, he founded the National Pituitary Agency, serving as its original director and remaining affiliated with it until 1985 when recombinant GH became available.

In 1974, The Endocrine Society recognized Bob’s critical role at the National Pituitary Agency and honored him with the Ayerst Award for distinguished service to the Society. In that same period, he served as president of the Lawson Wilkins Pediatric Endocrine Society and as acting chairman of the Department of Pediatrics at Johns Hopkins.

The Virginia years, 1974-1987, during which he served as chairman of the Department of Pediatrics at the University of Virginia, reflect Bob’s contributions to medicine beyond endocrinology. He founded the Children’s Medical Center, conceptually bringing together all faculty and health care workers serving children in the pursuit of a common mission which superseded departmental boundaries or funding sources. Bob was a key collaborator in the development of the University’s Clinical Research Center, the Diabetes Research Center, and the Department of Family Practice. He became a passionate advocate for children at the Virginia General Assembly on issues such as immunization, child abuse, restrictions on all-terrain vehicles, gun control, and Medicaid reimbursement.

Just as he inspired and trained pediatric endocrinologists from all over the world while at Johns Hopkins, the years at Virginia were characterized by a dramatic increase in academic pediatrics among University of Virginia medical students. The residency program more than doubled under Bob’s leadership, with more than half of the residents pursuing fellowship training in 14 pediatric subspecialties. Former residents from the University of Virginia serve as faculty members at 36 medical schools, the NIH, the Food and Drug Administration, and the Centers for Disease Control. They practice throughout the United States and Canada, as well as in Costa Rica, Iceland, the Marshall Islands, Nepal, and India.

Yet another significant phase of Bob’s unique contributions to academic medicine, and endocrinology in particular, might be termed the public advocacy years. He seemed to have developed an insight earlier than most of the rest of us of the role we would have to play if we were to remain preeminent as a nation in biomedical research. Beginning in 1970, he served as this Society’s representative to the Council of Academic Societies at the Association of American Medical Colleges and as chairman of the Society’s Public Affairs Committee. Subsequently, he served as a member of the Council of Government Affairs of the American Academy of Pediatrics and as a founding member of the Public Policy Council for pediatric societies.

Bob’s career has been truly remarkable, not simply for the myriad of accomplishments, but for the personal influence he has had on the many of us who have been his trainees and his friends. Sir William Osier, writing on personal ideals, characterizes well those attributes that distinguish Bob Blizzard for all who have been fortunate to know him:

“I have three personal ideals. One, to do the day’s work well and not to bother about tomorrow … . The second ideal has been to act the Golden Rule, as far as in me lay, toward my professional brethren and toward the patients committed to my care. And the third has been to cultivate such a measure of equanimity as would enable me to bear success with humility, the affection of my friends without pride, and to be ready when the day of sorrow and grief came to meet it with the courage befitting a man.”

Excerpted from Endocrinology, Volume 135, Number 2, August, 1994

References

| ↑1 | Bob Blizzard, Tom’s friend |

|---|