Juliet Henderson

I have always been interested in the politics of place. From my childhood family kitchen to the round portable Mongolian yurts I stayed in when travelling in the Gobi Desert; to the layout of Anglican churches contrasted with that of Quaker Meeting Houses; to tower blocks with faulty insulation, cladding, and lifts. All these tell stories of how physical environment reflects social structures and shapes human behaviour, for good and for bad.

Recently, like many, I have become more alert to the politics of public monuments, particularly in relation to our historical consciousness of colonialism, racism, and slavery. Simple questions arise. Why are certain people (mainly men) cast as suitable symbols to commemorate place or nation whilst others are forgotten? What does this suggest in terms of the social, historical, and moral justice views of the institutions that sanction and support such ideologically constructed public places? How might we address the collective norms that perpetuate old stories of a glorified past and ignore the injustices that enabled that ‘glory’?

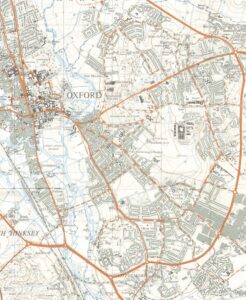

In Oxford we don’t have to look far for examples of such monuments and places: Rhodes’ statue on Oriel College, and the Codrington Library in All Souls constructed with money from the slaver Christopher Codrington, to name but two. The tour guide organization Uncomfortable Oxford offers a range of interesting walking tours and online resources exploring some of the less obvious links between Oxford University and the British Empire. These certainly chip away at normative representations of the university. As for my own form of witness towards injustice and racism, I and three others set up a Decolonising Florence Park street-names project two years ago. Here is our mission statement:

The streets of Florence Park, such as Clive Road, Campbell Road and Lytton Road, are named after key players in the East India Company, which was responsible for stripping India of its assets and trading in opium. It was instrumental in the British rule which led to 25 million deaths in India from war and famine. The men and the Company have absolutely no connection to the estate, which was constructed in the mid 1930s primarily for workers at the Morris car plant. Our aim is to create conversations, events and resources to promote discussion amongst today’s residents about colonialism and how it relates to our community.

At the same time, we want to explore our real and fascinating local history and how this intersects with wider social forces and historical events. We aim to involve as many local residents as possible in our activities and to keep the discussion going.

Next in our calendar of events is a talk by Dr Sebastian Pender, from Balliol College, on Friday 27 May at 19:00 in Florence Park Community Centre. Pursuing our central theme of inquiry – ‘What’s in a name?’ – the talk will explore issues of class, race, (de)colonisation, and the politics of commemoration, with a more particular focus on Major General Henry Havelock, Lieutenant General Sir James Outram, and Field Marshal Colin Campbell 1st Baron Clyde, after whom three local streets are named. Free tickets to the event and further details can be found here.

Friends are most welcome.

More articles in this month’s newsletter:

- May 2022

- Reflections during a zoom meeting 3 April

- Meeting for Worship 24 April

- The politics of place – and some local witnessing

- Monthly Appeal May 2022

- ‘Friendly Persuasion’

- Mutual Support Group – ‘Getting Older’

- Four Delusions and a Plea

- Note From the Gardening Team

- Britain Yearly Meeting is Seeking a Youth, Children, and Families Development Worker

- Waiting

- Living in the Spirit

- In Penn’s Shadow (1680-1720) – Philadelphia: The Great Experiment

- Addressing Environmental Issues as a Spiritual Community

- The Quakers: The Whites that helped the slavery abolishment

- Community Noticeboard Online, May 2022

- From Quaker Faith and Practice 24.21

- Meetings for Worship May 2022

Back to May 2022 Newsletter Main Page

Forty-Three Newsletter • Number 517 • May 2022

Oxford Friends Meeting

43 St Giles, Oxford OX1 3LW

Copyright 2022, Oxford Quakers