Nicole Gilroy

Book Review: For Thy Great Pain have Mercy on My Little Pain by Victoria MacKenzie (Bloomsbury, published 19/1/2023)

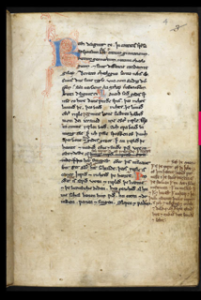

For a borderline atheist in lifetime recovery from an extreme Roman Catholic upbringing I do have a rather soft spot for medieval East Anglian Christianity. I studied medieval art and literature, falling completely in love with the outrageous marginal images in manuscripts and churches – the obscene carvings on misericords tucked underneath the pious monks’ bottoms, and the bizarre scenes with apes dressed as priests acted out on the margins of English psalters, the finest of which were made in East Anglia.

I even, in my misguided youth, took part in a couple of pilgrimages to Walsingham, carrying a 10ft wooden cross on foot from Nottingham through Holy Week, sleeping on church hall floors and spending the evenings singing bawdy songs and drinking too much beer. Maybe this is it – the Canterbury Tales trope of a very human attitude to religion, where Friars are openly lewd and everyone laughs about the corruption and hypocrisy of the nevertheless ubiquitous Church.

It is in this fifteenth-century Norfolk, ruled by a universal, all-powerful Church, yet where few of the folk really believe in it all, that Marjory Kempe and the woman who later became known as Julian of Norwich were born. They are valuable historical characters, in that they are the only medieval women whose voices survive from the horse’s mouth so to speak, though only Julian wrote with her own hand; Marjory was, as the majority of women were, entirely illiterate and relied on an unnamed scribe, possibly her son, to write down her Booke.

Both women felt the burning need to record their experiences, which were in both cases visions of Christ – Revelations of Divine Love in the case of Julian, and an ongoing personal relationship with Jesus: being present at the crucifixion, receiving direct advice and counsel, physical affection, and, indeed, sexual intimacy in the case of Marjory Kempe.

I heard the plug for this book on Front Row a few weeks ago, and ordered it the next morning, on the day of publication. It is a fictionalised account of the meeting between Kempe, a wealthy wife and mother to fourteen children, and Mother Julian of Norwich, daughter of a merchant and widowed mother. Julian became an anchoress – an extreme form of solitary contemplative life – after the death of both parents, her husband and her baby from the plague.

I’ll not spoil the story because there are only 176 pages to read. My copy is as I write already on its third reader in Oxford Meeting, and I’d gladly lend it further! I think it would be a tremendous discussion piece for a book club type event, or even just coffee chats. But for my tuppence-worth, and amongst many other things, I feel it is a valuable glimpse into the psychology of religious belief.

The devotion of Kempe and Mother Julian is intense and personal, and is in both cases under the scrutiny and criticism of male authorities. If the women’s visions are real, as they most certainly were to them, we can ponder on how those closest to their god, with the most personal channel to him, are policed by men who believe that only they have the right to this direct relationship.

I’m also struck by the nature of the two women’s faith. Julian is a sort of wise woman – she is literally walled up into her cell in a requiem mass, after which she must remain there until she dies, and will be buried under its floor. Yet she receives visitors at her window for a sort of unofficial confession, and is clearly sought after for her advice and counsel. In this way she serves the people. But Marjory’s faith is not about feeding the poor or improving the world. It is a personal love affair with Jesus, in which she spurns her husband and becomes the laughing stock of the county, in constant danger of prosecution for heresy.

It reminds me of the religion of my upbringing – the deep devotion and the encouragement to form a personal relationship with Jesus – one where you would talk to him, adore him and love him above all worldly things. I remember the little red publications handed out at church telling stories of devout, celibate Catholics who went about their daily work in the world but secretly mortified their flesh with spiked scapulars, put stones in their boots, and fasted endlessly. This sort of devotion was held in very high regard. I have since wondered about the strong echoes of mental illness in these religious expressions: self-harm, eating disorders, and the hearing of voices are all things that the church of my childhood considered desirable and holy. As the child of two psychiatric nurses I certainly noticed how so many seriously unwell people, including many of my parents’ patients were drawn to the more Gothic aspects of Catholic practice – songs about sheltering in the wounds of Christ, being bathed in blood and so forth. None of these devotions seem particularly useful to the world at large – they don’t feed the poor or clothe the naked for example, but perhaps they do, in a way, comfort the sick and dying.

The Jesus who appeared to Marjory Kempe told her to stop cutting her flesh as he didn’t want this from her. He told her not to fast so much, and to throw away her hairshirt. Can it be that Marjory – a woman who married a man she didn’t much like, who suffered from post-partum psychosis at least twice, treated by shackling her to her bed away from her child – found some sort of comfort and nurture in her visions that were simply not available to her in real life? Maybe she was incapable, emotionally or psychologically, of living out her faith by helping others, but she perhaps found a life she could bear to live in this way. Can it be that Julian, far more mentally stable, who married for love and felt real sorrow at the death of her husband and only baby, counselled her visitor in language and imagery that fitted with her world?

I have no idea. But it is a bloody good story. Read it and come tell me what you think.

This Month’s Forty-Three Newsletter Contents

- March 2023

- Children and Young People and Families Update

- Washing in Winter

- A Talk on the ‘Failure of Narrative’

- Call for a Counsellor

- Please Return Spare SALTO Key Cards

- Quaker Resonances in Psychoanalytic Thinking

- All-Age Worship: Sunday 5 March

- Monthly Appeal – March 2023

- EAPPI UK & Ireland are Recruiting for their Next Cohort of Human Rights Monitors!

- Book Review: For Thy Great Pain have Mercy on My Little Pain

- Post of Deputy General Manager Oxford Quaker Meeting

- Britain Yearly Meeting

- Oxford Quakers on Art

- How Do Quaker Meetings Do Outreach and Welcome Newcomers?

- SERVING OUTSIDE THE QUAKER COMMUNITY

- Oxford Meeting Quaker and Answer – March 2023

- From Quaker Faith and Practice

- Meetings for Worship – March 2023

Back to March 2023 Newsletter Main Page

Forty-Three Newsletter • Number 527 • March 2023

Oxford Friends Meeting

43 St Giles, Oxford OX1 3LW

Copyright 2023, Oxford Quakers