Denise Cullington

I discovered Quakerism’s muscular social/political roots when I was researching Salem, New Jersey (not the Massachusetts one). Founded in 1675 – two years prior to Burlington, and seven before Penn in Philadelphia – Salem was the first settlement in southern New Jersey. It’s a complicated story (as all history probably is when you start to look deeper), morally nuanced – and yet deeply impressive. We lose sight of the moral complexity to our cost.

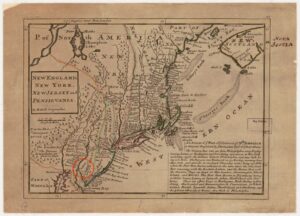

Red circle indicates area around Salem.

Library of Congress Collection

The Constitution offered to Salem settlers by John Fenwick (a Quaker and a landless younger son of gentry) was astonishing. It offered not only land (including for those indentured for four years), but freedom of worship (unlike the theocracy of the Puritans in the north), election of officials, non-imprisonment for debt, and trial by jury. (And for an accused native Lenape, half the jury were to be Lenape.) This was extraordinary; Fenwick’s constitution was later used by Penn in Pennsylvania, and subsequently in the US Bill of Rights.

The record of the first Quaker settlers is mixed. Quakers assumed that the trade goods they offered to the Lenape bought them rights to the land. The Lenape believed that these were reciprocal gifts offered in return for sharing the land that was for all, with the newcomers their brothers. They did not expect the white settlers to fence off their lands, channel mill streams which blocked the fishes’ route upriver to spawn, arrive in increasingly large numbers, nor bring disease. Five years after the first settlers’ arrival, smallpox decimated the Lenape community.

There are things to be proud of. Widow Abigail Lipincott in 1683 would have been one of the first to release her husband’s slaves. But there are also deeds of Quaker shame. It was William Penn’s son Thomas who conspired to trick the Lenape out of miles of land, in the infamous Walking Purchase (1737). It was not just nameless ‘white men’ who did it, but one of the Quakers’ own.

The story of those first Quakers isn’t one of spiritual courage alone, but also one of political and temporal battle for fairness. Quakerism emerged alongside the English Civil War (1642-49), and had two roots. One was a middle-class movement of gentry and City merchants against the nobility and large landowners; the other was a class war against the enclosures of common land which created destitution, and tithes to the established Church.

Proposals that land should be shared by everyone (the Diggers), or that the common lands should be taken back and given to the poor (the Levellers) had the support of many, not only foot-soldiers in the New Model Army and apprentices in the City.

The land-holding MPs and Grandees in the Army, led by Cromwell, tricked and suppressed these movements. Ringleaders were shot at Burford (1649) and the popular leader, John Lilburne, was exiled. The middle class had won.

Earlier that same year King Charles I had been executed. The man who was Captain of the Horse Guards at the execution was Sir John Fenwick – the very person who, twenty six years later, was to take that first settlement out to West Jersey. Within months of the regicide, Fenwick and many in the New Model became Quakers.

One can imagine what a help it was for those who had killed the King to have an account that was of finding God and His Truth within oneself.

In 1660 Charles II came to the throne. The Test Act, set up to control Charles and his Catholic wife, also netted Quakers. During Charles’ reign, countless Quakers were fined, 11,000 were imprisoned, 243 died, and others were transported. These were desperate times.

There was a way out, and I think it happened like this: A high-up Quaker, Edward Byllynge, confidant of George Fox, was found to have embezzled 40,000 of Quaker funds, an unimaginably huge amount. What did he do with this? Well, Charles II was at War with the Dutch in the New World and in the East Indies. Parliament kept an extremely tight grip on Charles’ funds. I think there was a deal: if the Quakers could quietly put aside their peace testimony and fund the war, in return new-won land would be made over to the Quakers to settle. (Historian Richard Allen, co-author of The Quakers: 1656-1723, agrees with this view.)

In 1672 George Fox visited this western half of New Jersey. These lands were offered to Byllynge for the small sum of 1,000, but Byllynge, still in gaol as a bankrupt, needed a frontman. A fellow soldier from New Model days, John Fenwick, served the purpose. The two men rapidly fell out over the agreed share of the lands. William Penn was called in to settle the matter quietly, away from scandal and the Courts. Penn was also lead Trustee responsible for selling Byllynge’s land and recouping the lost Quaker funds. He wrote Fenwick, “I took care to hide the original of the thing, because it reflects on you both and which is worse on the Truth.”

Penn interfered unhelpfully with Fenwick’s settlement. The two men later made their peace. When Rights of Government (independence from the crown of England and its taxes) were won in the Courts in 1680, one-time embezzler Byllynge was made Governor by the London Elders, in the face of furious opposition from the settlers. The London Elders must have needed to reward him or to buy his silence.

Byllynge died before he could come to the New World. His Governorship was sold to an absentee landlord with ties to the throne of Queen Anne, and who handed back the precious Rights of Government. So ended the first constitutional democracy, one hundred years prior to the Declaration of Independence.

Was this a shameful scandal? Assuming my version is right, it was an example of real-politique to put aside the Quaker peace testimony secretly, with the hope of great good: not only rescuing persecuted Quakers (the Truth) but establishing a good Society for all. Pacificism may need to be aligned with the preparedness for muscular action and risk. John Fenwick: what an extraordinary journey from the execution of a king, to the founding of a fairer Society.

| Next Article |

Back to March 2022 Newsletter Main Page

Forty-Three Newsletter • Number 515 • March 2022

Oxford Friends Meeting

43 St Giles, Oxford OX1 3LW

Copyright 2022, Oxford Quakers