Duration 10:17

Sexually Transmitted Infections

Plummer XD, Liang A

Clinical Case Applicability: pelvic inflammatory disease, infertility, chronic pelvic pain

Learning Objectives:

1. Understand the pathophysiology of common STIs

2. Describe the long-term sequelae of STIs

3. Understand the mechanism of action for treatment of common STIs

What is the pathophysiology of infectivity & treatment of these organisms? (HPV: see CIN script)

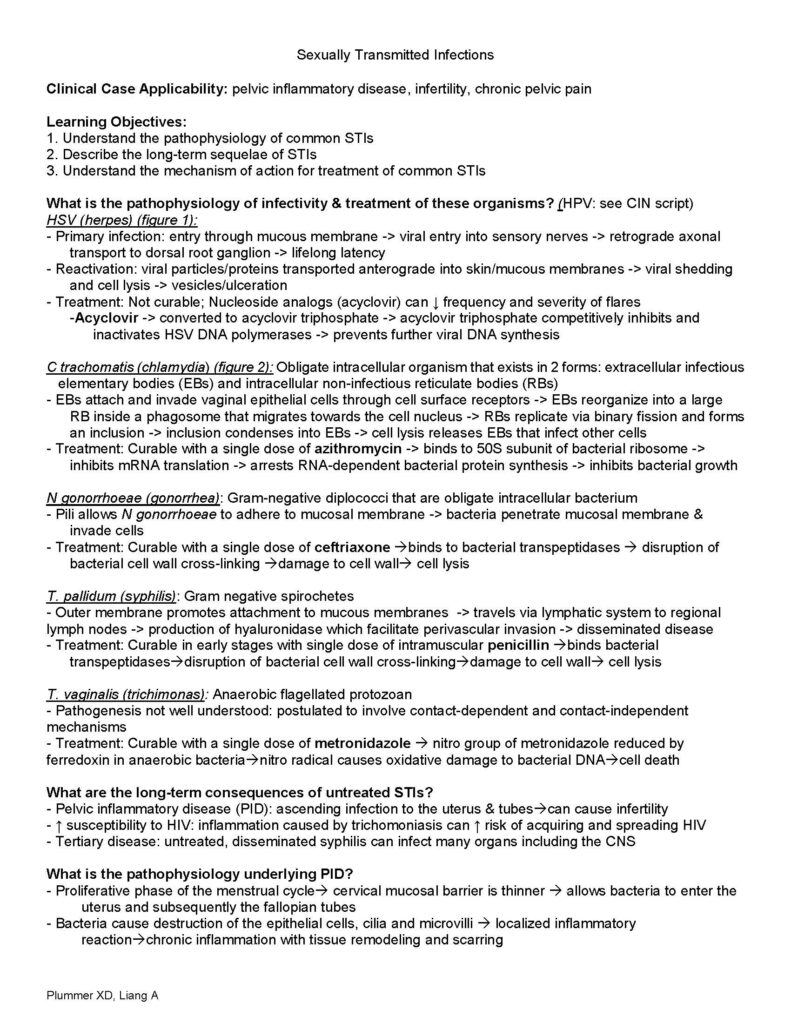

HSV (herpes) (figure 1):

– Primary infection: entry through mucous membrane -> viral entry into sensory nerves -> retrograde axonal transport to dorsal root ganglion -> lifelong latency

– Reactivation: viral particles/proteins transported anterograde into skin/mucous membranes -> viral shedding and cell lysis -> vesicles/ulceration

– Treatment: Not curable; Nucleoside analogs (acyclovir) can ↓ frequency and severity of flares

–Acyclovir -> converted to acyclovir triphosphate -> acyclovir triphosphate competitively inhibits and inactivates HSV DNA polymerases -> prevents further viral DNA synthesis

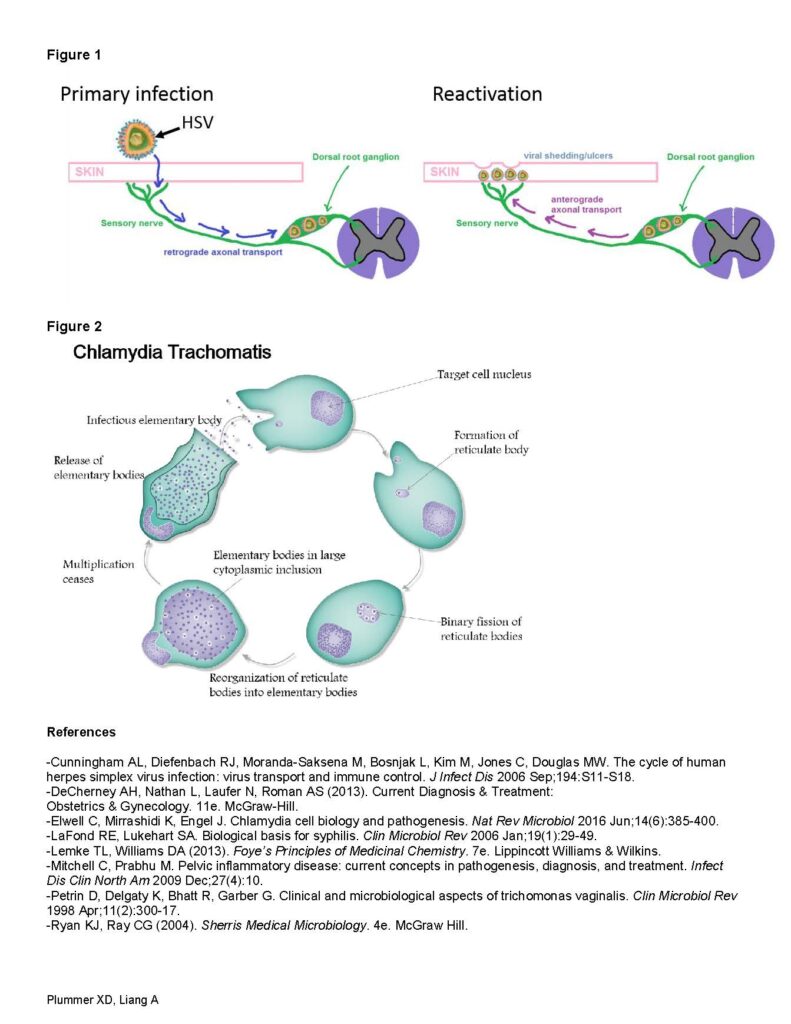

C trachomatis (chlamydia) (figure 2): Obligate intracellular organism that exists in 2 forms: extracellular infectious elementary bodies (EBs) and intracellular non-infectious reticulate bodies (RBs)

– EBs attach and invade vaginal epithelial cells through cell surface receptors -> EBs reorganize into a large RB inside a phagosome that migrates towards the cell nucleus -> RBs replicate via binary fission and forms an inclusion -> inclusion condenses into EBs -> cell lysis releases EBs that infect other cells

– Treatment: Curable with a single dose of azithromycin -> binds to 50S subunit of bacterial ribosome -> inhibits mRNA translation -> arrests RNA-dependent bacterial protein synthesis -> inhibits bacterial growth

N gonorrhoeae (gonorrhea): Gram-negative diplococci that are obligate intracellular bacterium

– Pili allows N gonorrhoeae to adhere to mucosal membrane -> bacteria penetrate mucosal membrane & invade cells

– Treatment: Curable with a single dose of ceftriaxone binds to bacterial transpeptidases disruption of bacterial cell wall cross-linking damage to cell wall cell lysis

T. pallidum (syphilis): Gram negative spirochetes

– Outer membrane promotes attachment to mucous membranes -> travels via lymphatic system to regional lymph nodes -> production of hyaluronidase which facilitate perivascular invasion -> disseminated disease

– Treatment: Curable in early stages with single dose of intramuscular penicillin binds bacterial transpeptidasesdisruption of bacterial cell wall cross-linkingdamage to cell wall cell lysis

T. vaginalis (trichimonas): Anaerobic flagellated protozoan

– Pathogenesis not well understood: postulated to involve contact-dependent and contact-independent mechanisms

– Treatment: Curable with a single dose of metronidazole nitro group of metronidazole reduced by ferredoxin in anaerobic bacterianitro radical causes oxidative damage to bacterial DNAcell death

What are the long-term consequences of untreated STIs?

– Pelvic inflammatory disease (PID): ascending infection to the uterus & tubescan cause infertility

– ↑ susceptibility to HIV: inflammation caused by trichomoniasis can ↑ risk of acquiring and spreading HIV

– Tertiary disease: untreated, disseminated syphilis can infect many organs including the CNS

What is the pathophysiology underlying PID?

– Proliferative phase of the menstrual cycle cervical mucosal barrier is thinner allows bacteria to enter the uterus and subsequently the fallopian tubes

– Bacteria cause destruction of the epithelial cells, cilia and microvilli localized inflammatory reactionchronic inflammation with tissue remodeling and scarring Plummer XD, Liang A

Figure 1

Figure 2

References

-Cunningham AL, Diefenbach RJ, Moranda-Saksena M, Bosnjak L, Kim M, Jones C, Douglas MW. The cycle of human herpes simplex virus infection: virus transport and immune control. J Infect Dis 2006 Sep;194:S11-S18.

-DeCherney AH, Nathan L, Laufer N, Roman AS (2013). Current Diagnosis & Treatment:

Obstetrics & Gynecology. 11e. McGraw-Hill.

-Elwell C, Mirrashidi K, Engel J. Chlamydia cell biology and pathogenesis. Nat Rev Microbiol 2016 Jun;14(6):385-400.

-LaFond RE, Lukehart SA. Biological basis for syphilis. Clin Microbiol Rev 2006 Jan;19(1):29-49.

-Lemke TL, Williams DA (2013). Foye’s Principles of Medicinal Chemistry. 7e. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

-Mitchell C, Prabhu M. Pelvic inflammatory disease: current concepts in pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment. Infect Dis Clin North Am 2009 Dec;27(4):10.

-Petrin D, Delgaty K, Bhatt R, Garber G. Clinical and microbiological aspects of trichomonas vaginalis. Clin Microbiol Rev 1998 Apr;11(2):300-17.

-Ryan KJ, Ray CG (2004). Sherris Medical Microbiology. 4e. McGraw Hill.

Duration 11:33

00:00

This VAP is on vagina discharge.

00:03

00:07

By the end of this VAP,

00:08

[AUDIO OUT]

00:09

00:21

The normal vaginal environment

00:22

is acidic, with a pH of 3.8

00:25

to 4.4, thus discouraging

00:27

infections.

00:29

This environment is created

00:30

by normally occurring bacteria,

00:31

lactobacilli.

00:34

Any disruption to the pH balance

00:36

of the vaginal environment

00:37

can make it more

00:38

conducive to infection.

00:40

Physiological vaginal discharge

00:42

is normal and consists

00:44

of vaginal secretions.

00:46

Contribution

00:46

to vaginal secretions

00:47

include secretions

00:49

from sebaceous, sweat, Bartholin

00:52

and Skene glands,

00:53

transudate

00:54

from the vaginal wall,

00:55

exfoliated vaginal and cervical

00:58

cells, cervical mucus,

01:00

endometrial and oviductal fluid.

01:03

Physiological discharge is also

01:05

influenced by hormone levels.

01:07

The pH balance of the vagina

01:09

is the least acidic on the days

01:11

just prior

01:11

to and during menstruation.

01:14

Infections are thus most common

01:15

at this time.

01:17

There is also a normal increase

01:19

of discharge around mid-cycle.

01:22

Pregnancy also increases

01:23

physiological discharge.

01:24

01:28

Vaginal discharge can be

01:29

either physiological or

01:31

pathological.

01:32

Pathological causes can be

01:34

further divided

01:35

into infective or non-infective

01:37

causes.

01:38

The commonest cause

01:39

is physiological,

01:41

but infective causes should be

01:42

excluded.

01:44

We will be focusing

01:44

on the major common causes

01:46

of infective vaginal discharge–

01:48

namely bacterial vaginosis,

01:51

vulvovaginal candidiasis,

01:53

and trichomonas vaginalis.

01:54

01:58

The following diagnostic

01:59

approach is recommended.

02:01

First, a thorough history must

02:03

be obtained.

02:04

Details

02:05

about the vaginal discharge

02:06

include the onset, duration,

02:09

color, and odor.

02:11

Associated symptoms

02:12

such as vaginal itch, rash,

02:14

and dysuria

02:15

are

02:16

suggestive of infective vaginal

02:18

discharge.

02:19

A sexual history is used

02:21

to assess the risk of STIs.

02:24

Risk factors include age less

02:26

than 25 years,

02:27

change of new sexual partner

02:29

in the last year,

02:30

and more than one sexual partner

02:32

in the last year.

02:33

Similar symptoms in partners

02:35

should be covered.

02:37

Medical history is important

02:38

as immunocompromised states

02:40

like diabetes and HIV

02:42

can predispose to infection.

02:44

Current and previous medication,

02:46

menstrual history,

02:47

and obstetric history

02:49

should be obtained, too.

02:51

Next, perform

02:53

a physical examination,

02:54

inspection

02:55

of the external genitalia

02:57

and perianal areas

02:59

are done to look

02:59

for inflammation and other

03:01

lesions.

03:02

A speculum examination allows

03:04

one to inspect

03:05

the vaginal and cervical region.

03:08

Attention to the appearance

03:09

and character of discharge

03:10

is important, including

03:12

the consistency and odor.

03:16

Not all women

03:17

with vaginal discharge

03:18

require investigations.

03:20

Empirical treatment can be given

03:22

if the patient is at low risk

03:23

of STI and has no symptoms

03:26

to suggest upper genital tract

03:27

infection.

03:29

The description

03:30

in the top right blue box

03:32

gives a clue

03:33

as to the potential infection.

03:36

Investigations are indicated

03:37

if a woman is at high risk

03:39

of STIs, has symptoms suggestive

03:42

of upper genital tract

03:44

infection– for example,

03:46

abdominal pain, dyspareunia,

03:49

or fever, has previous treatment

03:51

which has failed, is post-natal,

03:54

post-miscarriage,

03:55

or post-abortion,

03:57

but is within three weeks

03:58

of insertion

03:59

of an intrauterine contraceptive

04:01

device.

04:03

Investigations include

04:04

high vaginal swabs, which are

04:06

used to diagnose a common cause

04:08

such as candida,

04:09

bacterial vaginosis,

04:11

and trichomonas.

04:13

Endocervical swabs are used

04:15

to diagnose certain sexually

04:16

transmitted diseases

04:18

like chlamydia and gonorrhea.

04:20

04:23

Bacterial vaginosis is the most

04:25

common cause

04:26

of vaginal discharge in women

04:27

of reproductive age.

04:29

However, up to 50%

04:31

of women

04:31

with a clinical diagnosis of BV

04:33

are asymptomatic.

04:36

BV is due to an overgrowth

04:37

of organisms.

04:38

This occurs when there is

04:39

an alteration

04:40

of normal vaginal flora,

04:42

causing a loss of lactobacilli,

04:44

thus disrupting the pH balance

04:46

of the vaginal environment

04:47

and increasing the pH.

04:50

The organisms responsible

04:51

are predominantly anaerobic,

04:53

and include Gardnerella

04:55

vaginalis, Mycoplasma hominis,

04:57

and Mobiluncus.

04:59

An isolation of Gardnerella

05:01

vaginalis alone should not

05:03

be used as a diagnostic test

05:04

for BV, as between 35% to 55%

05:07

of women

05:08

are carriers of this organism.

05:11

Predisposing factors include

05:13

repeated alkalinization

05:14

of the vagina– for example,

05:16

douching

05:17

and frequent sexual intercourse.

05:20

BV increases the risk

05:21

of post-abortion endometritis

05:23

and pelvic inflammatory disease.

05:26

In pregnancy, it is associated

05:28

with late miscarriage, preterm

05:30

delivery

05:31

in high-risk pregnancies,

05:33

preterm premature rupture

05:34

of membranes,

05:35

and postpartum endometritis.

05:36

05:40

BV is usually diagnosed using

05:42

Amsel’s criteria,

05:43

where at least three

05:44

of the following four conditions

05:46

must be met.

05:48

Number one, a raised vaginal pH

05:50

of more than 4.5; number two,

05:53

thin, homogenous grey or white

05:55

vaginal discharge; number three,

05:58

the presence of clue cells

06:00

on wet preparation microscopy;

06:02

and number four, a positive

06:04

amine test demonstrated

06:05

by the release of the fishy odor

06:07

on mixing vaginal discharge with

06:09

10% potassium hydroxide.

06:11

Organisms are cultured

06:13

from a high vaginal swab

06:14

for diagnosis.

06:14

06:18

All symptomatic women

06:19

with bacterial vaginosis

06:21

or asymptomatic women with BV

06:23

before surgical procedures

06:25

should be treated.

06:27

BV can be treated

06:28

with either oral Metronidazole

06:30

or Clindamycin for seven days.

06:33

Treatment in pregnancy

06:34

is the same as

06:35

in non-pregnant women.

06:37

Overall cure rates range

06:38

from 75% to 85% and followup is

06:41

not necessary if symptoms

06:43

resolve.

06:44

Recurring BV occurs within three

06:46

months of treatment in about 15%

06:49

of women.

06:50

Suppressive regimens may be

06:52

considered, but evidence

06:53

to support their effectiveness

06:55

is limited.

06:56

Maintenance

06:57

with acetic acid vaginal gel

06:59

at the time of menstruation

07:01

and following unprotected

07:02

sexual intercourse maintains

07:04

acidic vaginal pH.

07:05

07:08

Candidiasis is

07:09

a fungal infection mostly caused

07:11

by the species Candida albicans.

07:15

Candida albicans

07:16

is responsible for 80% to 92%

07:18

of cases.

07:20

Other species of Candida

07:21

such as Candida glabrata

07:23

and Candida tropicalis

07:24

tend to be resistant to therapy.

07:27

Predisposing factors

07:28

to infection

07:29

include immunosuppression,

07:32

antibiotic use, high estrogen

07:34

levels that occur

07:35

with oral contraceptive pills

07:37

and hormone replacement therapy

07:39

usage, pregnancy, diabetes

07:42

mellitus, and prolonged

07:43

corticosteriod therapy.

07:45

07:48

Typical Candida infection

07:50

presents

07:50

with thick, white, curdy cottage

07:52

cheese-like discharge

07:54

associated with vaginal itch

07:56

and soreness.

07:57

Occasionally, it can be

07:59

associated

07:59

with superficial dyspareunia

08:02

or external dysuria.

08:04

Clinically,

08:05

vulvovaginal erythema

08:07

and excoriation is common.

08:09

The high vaginal swab is used

08:11

for diagnosis.

08:12

Yeast cells are seen on gram

08:14

stain microscopy.

08:15

08:18

There are various preparations

08:20

of drugs that can be used

08:21

for treatment.

08:22

All topical and oral azole

08:24

therapies give a cure rate

08:26

of 80% to 90%.

08:28

In pregnancy,

08:29

asymptomatic colonization

08:31

with Candida is common at 30%

08:33

to 40%.

08:35

No treatment is necessary,

08:37

unless patients are symptomatic.

08:39

Oral azole is contraindicated

08:42

and should not be used

08:42

in pregnancy.

08:44

Longer courses of topical azole

08:46

for 7 days is recommended

08:48

instead.

08:49

Nystatin preparations have a 70%

08:51

to 90% cure rate.

08:53

They are the first line

08:54

treatment

08:55

for non-albicans infection.

08:58

Patients should avoid

08:59

local irritants

09:00

such as tight clothing

09:02

or perfumed vaginal douche.

09:04

Topical creams or antihistamines

09:06

can be used to relieve itch.

09:08

09:11

Recurrent infection is defined

09:13

as four or more episodes

09:15

of symptomatic infection

09:16

annually,

09:17

with positive microscopy

09:18

of Candida on at least two

09:20

episodes.

09:21

For acute treatment

09:23

of the infection, an induction

09:24

regimen of oral azole

09:26

is repeated every three days

09:27

for three doses.

09:29

Following that, [INAUDIBLE]

09:30

maintenance regimen is used

09:32

for six months.

09:33

09:35

Trichomonal vaginitis is caused

09:38

by the parasite Trichomonas

09:40

vaginalis.

09:41

It is

09:41

the only sexually transmitted

09:43

vaginal infection of the three

09:45

infections discussed.

09:47

However, unlike chlamydia

09:49

and gonorrhea, it does not

09:51

affect extragenital sites,

09:53

but can infect the vagina,

09:54

urethra, and periurethral

09:56

[INAUDIBLE].

09:58

Partners in the last two months

09:59

should be screened and treated.

10:01

Testing for other sections

10:03

including BV and other STIs

10:05

should be considered,

10:06

as 60% of patients

10:08

have BV and 30%

10:09

have chlamydia or gonorrhea.

10:12

The graph shows

10:13

the concurrent STIs found

10:14

in a survey of women

10:15

with a Trichomonas infection.

10:17

10:20

Clinical diagnosis is typically

10:22

identified

10:23

by a yellow green foul-smelling

10:24

discharge associated

10:26

with vulvovaginal erythema

10:28

and excoriation

10:29

with a “strawberry cervix”

10:31

presenting in 2% of patients.

10:33

Investigations will review

10:35

a raised pH

10:36

with motile trichomonads seen

10:38

on microscopy.

10:39

10:42

First line treatment requires

10:44

systemic rather than

10:45

topical treatment,

10:46

because the infection is not

10:47

always confined to the vagina

10:49

but may involve other parts

10:50

of urogenital tract.

10:53

Oral Metronidazole for one week

10:55

gives a cure rate of 90% to 95%,

10:57

compared to 50%

10:59

with topical treatment.

11:01

Patients

11:02

with persistent symptoms

11:03

should be retreated

11:04

with oral Metronidazole 400 mg

11:06

b.i.d.

11:07

for another seven days.

11:09

Repeated failure of treatment

11:10

may require high dose

11:12

oral Metronidazole of two grams

11:13

daily for three days.

11:15

Sexual partners should also

11:17

be treated as this will improve

11:18

cure rates.

11:19

11:22

This is the end of the VAP.

11:24

Further reading references are

11:25

as stated.

Duration 6:55

Welcome.

00:02

Today, we will review

00:03

pelvic inflammatory disease.

00:05

00:08

Our objective today will be

00:09

to briefly review

00:10

the definition, epidemiology,

00:12

and pathogenesis

00:13

of pelvic inflammatory disease,

00:16

which I will refer to as PID

00:18

in this presentation.

00:19

We’ll review

00:20

the important long term sequelae

00:22

associated with PID

00:24

that makes it

00:24

such a public health concern.

00:26

We will also discuss diagnosis

00:28

and first line treatment

00:29

for PID.

00:30

00:33

Here is an outline

00:34

of the presentation today.

00:36

00:42

Pelvic inflammatory disease

00:44

is a spectrum

00:45

of inflammatory disorders

00:46

of the upper female genital

00:48

tract, which includes

00:49

the uterus, fallopian tubes,

00:51

and ovaries.

00:52

It is believed to be caused

00:54

by ascending spread

00:55

of microorganisms

00:56

from the vagina

00:57

to the cervix, endometrium,

00:59

fallopian tubes,

01:00

and/or adjacent structures.

01:02

01:05

The rate of PID in the United

01:07

States population has gone down

01:09

over the last 10 to 20 years.

01:11

Most likely, this

01:12

is due to the use

01:13

of prophylactic antibiotics

01:15

prior to surgical procedures,

01:17

routine screening of high risk

01:18

populations for sexually

01:20

transmitted infection,

01:21

and to the use of antibiotics

01:23

early in patients in which lower

01:25

genital infections,

01:26

such as cervicitis,

01:27

is suspected.

01:28

01:31

PID it’s

01:32

a polymicrobial infection.

01:35

The most common bacteria

01:36

isolated in cases of PID

01:38

are anaerobic bacteria,

01:40

chlamydia trarchomatis,

01:42

and neisseria gonorrhea.

01:43

01:46

Certain high risk populations

01:48

should be watched closely

01:49

for evidence of PID.

01:51

In particular, sexually active

01:53

young women, patients attending

01:54

sexually transmitted disease

01:56

clinics, and patients who live

01:57

in other settings

01:58

where there are high rates

01:59

of gonorrhea or chlamydia

02:01

are at risk.

02:02

02:05

A clinical diagnosis

02:06

of symptomatic PID

02:08

has a positive predictive value

02:10

at 65% and 90%,

02:12

compared with laparoscopy, which

02:14

is thought to be

02:14

the gold standard for diagnosis

02:17

based on early studies.

02:19

Today, the diagnosis of PID

02:21

is primarily made using

02:22

this clinical criteria.

02:24

Of note, the diagnosis of PID

02:27

requires ruling out other causes

02:29

of abdominal pain,

02:30

such as appendicitis,

02:32

ectopic pregnancy,

02:33

or other surgical emergencies.

02:36

Treatment should be initiated

02:37

if patients have at least one

02:38

of the minimum criteria listed

02:40

here,

02:41

which are cervical motion

02:42

tenderness, uterine,

02:43

or adnexal tenderness.

02:45

Further work

02:46

up for alternative etiology

02:47

of pain should not delay

02:48

treatment.

02:50

According to the Center

02:51

for Disease Control

02:52

and Prevention, other criteria

02:54

that may increase

02:55

your specificity

02:56

for the diagnosis of PID

02:58

include fever,

02:59

mucopurulent vaginal discharge,

03:02

numerous white blood cells

03:04

on a wet mount, and/or detection

03:06

of gonorrhea or chlamydia.

03:08

The most specific tests

03:10

for diagnosis

03:11

include endometrial biopsy,

03:13

ultrasound evidence

03:14

of tubo-ovarian abscess,

03:16

and/or diagnostic laparoscopy.

03:19

However, due to the increased

03:21

risk of long term morbidity

03:23

associated with failing to treat

03:24

a patient with PID,

03:26

it is recommended

03:27

that a high level

03:27

of clinical suspicion

03:29

be maintained

03:29

and that patients

03:30

with minimum criteria

03:31

be empirically treated early.

03:33

03:36

In the short term, treatment

03:38

is aimed

03:39

at clinical and microbiologic

03:41

cure.

03:42

This can be reliably achieved

03:43

with antibiotic regimens,

03:45

as described

03:46

on the next few slides.

03:48

Less is known about the effect

03:49

of current regimens

03:50

on long term outcomes.

03:52

However, it is thought

03:53

that by early detection

03:55

and treatment of PID,

03:56

it is possible to decrease

03:58

the rates of infertility,

03:59

ectopic pregnancy,

04:01

recurrent infection,

04:02

and chronic pelvic pain

04:03

that can be the long term

04:04

sequelae.

04:05

04:08

Certain patients are candidates

04:10

for outpatient treatment

04:11

in the setting of PID,

04:13

and there does not appear to be

04:14

any benefit of inpatient

04:15

over outpatient therapy

04:17

if they meet criteria

04:18

for outpatient management.

04:20

Appropriate regimens should

04:21

empirically cover gonorrhea

04:23

and chlamydia.

04:24

If the clinical picture is

04:25

concerning

04:26

for anaerobic infection–

04:27

for instance,

04:28

if bacterial vaginosis is

04:29

detected– then consideration

04:31

may be given to adding

04:33

an antibiotic with broader

04:34

anaeorbic coverage,

04:35

such as Metronidazole.

04:36

04:39

Certain populations will require

04:41

closer monitoring

04:42

and in patient parenteral

04:43

therapy.

04:44

These include patients who are

04:46

pregnant, those in whom

04:48

a surgical emergency may

04:49

be suspected,

04:50

such as appendicitis, patients

04:52

who have not responded

04:53

to oral medications

04:55

or are unable to tolerate

04:56

outpatient oral regimen, those

04:58

who demonstrate

04:59

other signs of severe illness,

05:00

or have radiologic findings

05:02

concerning

05:03

for a tubo-ovarian abscess.

05:04

05:07

Per the Center for Disease

05:09

Control, the recommended

05:10

first line treatment

05:11

includes a cephalosporin

05:12

with broader anaerobic coverage,

05:14

such Cefotetan or Cefotxitin,

05:16

with Doxycycline for a total

05:18

of 14 days.

05:19

After clinical symptoms improve,

05:21

patients may continue

05:22

Doxycycline

05:23

with or without Metronidazole

05:25

for a total of 14 days.

05:27

There are many alternatives

05:28

to this regimen, and there’s

05:29

limited evidence

05:30

that any regimen is better

05:31

than the other.

05:32

05:35

Whether patients are treated

05:36

as inpatients or outpatients,

05:38

the patient should be followed

05:40

closely and clinical improvement

05:42

should be seen within three days

05:43

of initiation of therapy.

05:45

Repeat testing and completion

05:47

of screening for any sexually

05:48

transmitted diseases

05:49

within three to six months

05:50

should be performed.

05:52

Patients

05:52

with pelvic inflammatory disease

05:54

are at high risk of recurrence.

05:56

All patients diagnosed

05:57

with gonorrhea and/or chlamydia

05:59

should also have testing

06:00

in treatment

06:00

of their sexual partners.

06:01

06:05

In summary, pelvic inflammatory

06:07

disease

06:08

is a polymicrobial disease

06:09

with significant public health

06:10

implications,

06:11

including increased risk

06:13

of ectopic pregnancy,

06:14

infertility,

06:15

and chronic pelvic pain.

06:17

Early detection

06:18

and effective treatment

06:19

is required to decrease

06:21

long terms sequelae.

06:22

Evidence suggests

06:23

that outpatient oral therapy is

06:25

equally effective for treatment

06:27

of mild

06:27

to moderate PID

06:29

as inpatient parenteral therapy

06:31

in certain clinical situations.

06:33

It is very important to remember

06:34

to screen for other sexually

06:36

transmitted diseases in patients

06:38

diagnosed with PID,

06:39

and their partners.

06:40

06:43

Here are my key references.

06:44

06:47

Here are acknowledgements.

06:48

06:52

Thank you.