The “tactical field care” phase is distinguished from the “care under fire” phase by having more time available to provide care and a reduced level of hazard from hostile fire.

a. The time available to render care may be quite variable.

In some cases, tactical field care may consist of rapid treatment of wounds with the expectation of a reengagement of hostile fire at any moment. In some circumstances, there may be ample time to render whatever care is available in the field. The time to evacuation may be quite variable from minutes to several hours.

b. If a victim of a blast or penetrating injury is found without a pulse, respirations, or other signs of life, do not attempt cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR).

Attempts to resuscitate trauma casualties in arrest have found to be futile even in the urban setting where the victim is in close proximity to a trauma center. On the battlefield, the cost of attempting CPR on casualties with what are inevitably fatal injuries will be measured in additional lives lost as care is withheld from casualties with less severe injuries and as soldier medics are exposed to additional hazard from hostile fire because of their attempts. Only in the case of non-traumatic disorders, such as hypothermia, near drowning, or electrocution, should CPR be considered. Casualties with an altered level of consciousness should be disarmed immediately. Remove both weapons and grenades. This provides a safety measure for the care providers. When the casualty becomes more awake and alert he could mistake the good guys for the enemy he was recently engaging.

c. Initial assessment consists of airway, breathing, and circulation.

d. Oxygen is usually not available in this phase. Cylinders of compressed gas and the associated equipment for supplying the oxygen are too heavy to make their use in the field feasible.

e. Breathing.

(1) Traumatic chest wall defects should be closed with an occlusive dressing without regard to venting one side of the dressing, as this is difficult to do in a combat setting. You may use an Asherman chest seal (lesson 3) if one is available.

(2) If you are taping a field dressing envelope or other airtight material over an open chest wound, tape all four sides of the material to the chest as long as the care provider has the ability to needle decompress a possible tension pneumothorax. If the ability to needle decompress the chest is not available, the occlusive dressing should only be taped on three sides to allow a flutter valve effect in the dressing.

NOTE: Tension pneumothorax is the second leading cause of preventable battlefield death.

f. Bleeding.

(1) The soldier medic should now address any significant bleeding sites not previously controlled. He should only remove the absolute minimum of clothing required to expose and treat injuries, both because of time constraints and the need to protect the patient from environmental extremes.

(2) Significant bleeding should be stopped as quickly as possible using a tourniquet as described previously. Once the tactical situation permits, consideration should be given to loosening the tourniquet and using direct pressure, a pressure dressing, a chitosan hemostatic dressing, or a hemostatic powder (QuikClot) to control any additional hemorrhage. Do not completely remove the tourniquet, just loosen it and leave in place. If hemorrhage continues, the tourniquet should be retightened and left alone.

g. Intravenous access.

(1) Intravenous access should be gained next. Although advanced trauma life support (ATLS) recommends starting two large-bore (14- or 16- gauge) intravenous infusions (IVs), the use of a single 18-gauge catheter is preferred in the field setting because of the ease of starting the infusions and because it also serves to ration supplies.

(2) Heparin or saline lock-type access tubing should be used unless the patient needs immediate fluid resuscitation. Flushing the saline lock every two hours will usually suffice to keep it open without the need to use a heparin solution.

(3) Soldier medics should ensure the IV is not started distal to a significant wound.

(4) If you are unable to initiate a peripheral IV, consideration should be given to starting a sternal intraosseous (IO) line to provide fluids. When unable to gain vascular access through a peripheral vein, an IO device can be used to gain access through the sternum. The First Access for Shock and Trauma (F.A.S.T.1) device is available and allows the puncture of the manubrium of the sternum and administration of fluids at rates similar to IVs. See figure 1-3.

h. Intravenous fluids.

(1) One thousand milliliters (ml) of Ringer’s lactate (2.4 pounds) will expand the intravascular volume 250 ml within one hour.

(2) Five hundred ml of 6 percent hetastarch (trade name Hextend®) weighs 1.3 pounds and will expand the intravascular volume by 800 ml within one hour. One 500 ml bag of Hextend® solution is functionally equivalent to three 1,000 ml bags of lactated Ringer’s. There is more than a 5 1/2 pound advantage in the overall weight-to benefit ratio (1.3 lbs to 7.2 lbs, respectively). The expansion using Hextend® is sustained for at least eight hours. For these reasons, Hextend® is the fluid of choice. See figure 1-4 for an illustration of an IV bag of Hextend®.

(3) The first consideration in selecting a resuscitation fluid is whether to use a crystalloid or colloid solution. Crystalloids are fluids such as Ringer’s lactate or normal saline where sodium is the primary osmotically-active solute. Since sodium eventually distributes throughout the entire extracellular space, most of the fluids in crystalloid solutions remain in the intravascular space for only a limited time. Colloids such as Hextend® are solutions where the primary osmotically active molecules are of greater molecular weight and do not readily pass through the capillary walls into the interstitial space. These solutions are retained in the intravascular space for a much longer period than crystalloids. In addition, the oncotic pressure of colloid solutions may result in an expansion of the blood volume that is greater than the amount infused.

i. Any significant extremity or truncal wound (neck, chest, abdomen, and pelvis), with or without obvious blood loss or hypotension, may require intravenous infusion.

(1) If the casualty is coherent and has a palpable radial pulse, blood loss has likely stopped. Initiate a saline lock, hold fluids, and re-evaluate as frequently as the situation allows.

(2) If there is significant blood loss from any wound and the casualty has no radial pulse or is not coherent, STOP THE BLEEDING by whatever means available (tourniquet, direct pressure, hemostatic dressing [HemCon™], or hemostatic powder [QuikClot]). However, greater than 90 percent of hypotensive casualties suffer from truncal injuries that are not corrected by these resuscitative measures. These casualties will have lost a minimum of 1,500 ml of blood (30 percent of their circulating volume). After hemorrhage is controlled to the extent possible, start 500 ml of Hextend®. If mental status improves and the radial pulse returns, maintain the saline lock and hold fluids.

(3) If no response is seen, within 30 minutes, give an additional 500 ml. of Hextend® and monitor vital signs. If no response is seen after 1,000 ml of Extend®, consider triaging supplies and giving attention to more salvageable casualties. Remember, this amount is equivalent to more than 6 liters of Ringer’s lactate.

(4) Because of the need to conserve existing supplies, no casualty should receive more than 1,000 ml of Hextend®.

(5) Uncontrolled thoracic or intra-abdominal hemorrhage needs rapid evacuation and surgical intervention. If this is not possible, determine the number of casualties verses the amount of available fluids. If supplies are limited or casualties are numerous, determine if fluid resuscitation is recommended.

NOTE: A number of studies involving uncontrolled hemorrhage models have clearly established that aggressive fluid resuscitation in the setting of unprepared vascular injury is either of no benefit or results in an increase in blood loss and/or mortality when compared to no fluid resuscitation or hypotensive resuscitation. Several studies noted that only after uncontrolled hemorrhage was stopped did fluid resuscitation prove to be of benefit.

j. Dress wounds to prevent further contamination and help hemostasis. Emergency trauma dressings (Israeli bandages) are ideal for this. Check for additional wounds (exit wounds) since the high velocity projectiles from modern assault rifles may tumble and take erratic courses when traveling through tissues, often leading to exit sites that are remote from the entry wound.

k. Only remove enough clothing to expose and treat wounds. Care must be taken to protect the casualty from hypothermia. Casualties who are hypovolemic become hypothermic quite rapidly if traveling in a CASEVAC or MEDEVAC asset and are not protected from the wind, regardless of the ambient temperature. Protect the casualty by wrapping them in a protective wrap (Blizzard Rescue Wrap®)

l. Pain control.

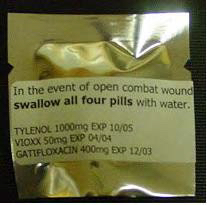

(1) If the casualty is able to fight, administer meloxicam (Mobic™) 15 milligrams (mg) taken orally (PO) initially with two 650 mg of acetominophen (bi-layered Tylenol® caplets) every eight hours. Along with an antibiotic, this makes up the “combat pill pack” depicted figure 1-5.

(2) If the casualty is unable to fight, 5 mg IV morphine may be given every 10 minutes until adequate pain control is achieved. If a saline lock is used, it should be flushed with 5 ml of saline after the morphine administration. Ensure there is some visible indication of time and amount of morphine given. Document the morphine administration on the casualty’s field medical card (FMC).

m. Fractures should be splinted as circumstances allow. Perform pulse, motor, and sensory (PMS) checks before and after splinting.

n. Antibiotics should be considered in all battlefield wounds since these type wounds are prone to infection. Infection is a late cause of morbidity and mortality in wounds sustained on the battlefield.

o. Combat is a frightening experience, especially if wounded. Reassure the casualty. This can be simply telling him that you are there and are going to take care of him. It can be as effective as morphine in relieving anxiety. Explain the care that is being given.

p. Document clinical assessments, treatment rendered, and changes in the casualty’s status. Forward the documentation with the casualty to next level of care.