|

Medical Education Division |

Operational Medicine 2001

Standard First Aid Course

NAVEDTRA 13119

Bones, Joints and MusclesAccidents cause many different types of injuries to bones, joints and muscles. When rendering first aid, you must be alert for signs of broken bones (fractures), dislocations, sprains, strains, and bruises (contusions). Injuries to the joints and muscles often occur together, and it is difficult to tell whether the injury is to a joint, muscle, or tendon. It is difficult to tell joint or muscle injuries from fractures. When in doubt, always treat the injury as a fracture. The primary process of first aid for fractures consists of immobilizing the injured part to prevent the ends of broken bones from moving and causing further damage to the nerves, blood vessels, or internal organs. Splints are also used to immunize injured joints or muscles and to prevent the enlargement of severe wounds. Before learning first aid for injuries to the bones, joints, and muscles, you need to have a general understanding of the use of splints. Splints In an emergency, almost any firm object or material will serve as a splint. Thus, umbrellas, canes, rifles, sticks, oars, wire mesh, boards, cardboard, pillows, and folded newspapers can be used. A fractured leg can be immobilized by securing it to the uninjured leg. Whenever possible, use ready-made splints such as the pneumatic or traction splints. Splints should be lightweight, padded, strong, rigid, and long enough to reach the joint above and below the fracture. If they are not properly padded, they will not adequately immobilize the injured part. Articles of clothing, bandages, blankets, or any soft material may be used as padding. If the casualty is wearing heavy clothes, you may be able to apply the splint on the outside, allowing the clothing to serve as a part of the required padding. Fasten splints in place with bandages, adhesive tape, clothing, or any suitable material. One person should hold the splints in position while another person fastens them. Splints should be applied tight, but never tight enough to stop the circulation of blood. When applying splints to the arms or legs, leave the fingers or toes exposed. If the tips of the fingers or toes turn blue or cold, loosen the splints or bandages. Injuries will probably swell, and splints or bandages that were applied correctly may later be too tight. Fractures A break or rupture in a bone is called a fracture. There are two basic types; open and closed. A closed fracture does not produce an open wound in the skin, also known as a simple fracture (Fig. 6-lA). An open fracture produces an open wound in the skin, also known as a compound fracture (Fig. 6-1B). Open wounds are caused by the sharp end of broken bones pushing through the skin; or by an object such as a bullet that enters the skin from the outside. Open fractures are usually more serious than closed fractures. They involve extensive tissue damage and are likely to become infected. Closed fractures can be turned into open fractures by rough or careless handling of the casualty. Always use extreme care when treating a suspected fracture.

Figure 6-1 - Types of Fractures It is not easy to recognize a fracture. All fractures, whether open or closed, can cause severe pain or shock. Fractures can cause the injured part to become deformed, or to take an unnatural position. Compare the injured to the uninjured part if you are unsure of a deformity. Pain, discoloration, and swelling may be at the fracture site, and there may be instability if the bone is broken clear through. It may be difficult or impossible for the casualty to move the injured part. If movement is possible, the casualty may feel a grating sensation (crepitus) as the ends of the bones rub against each other. If a bone is cracked rather than broken, the casualty may be able to move the injured part without much difficulty. An open fracture is easy to see if the end of the bone sticks out through the skin. If the bone does not stick out, you might see a wound but fail to see the broken bone. It can be difficult to tell if an injury is a fracture, dislocation, sprain, or strain. When in doubt, splint. If you suspect a fracture, do the following: 1. Control bleeding with direct pressure, indirect pressure, or tourniquet only as a last resort. 2. Treat for shock. 3. Monitor the airway, breathing, and circulation (ABCs). 4. Remove all jewelry from the injury site, unless the casualty objects. Gently cut clothing away so that you don't move the injured part and cause further damage. 5. Check the distal pulse of the injured part, if pulse is absent, gently move injured part to restore circulation. 6. Cover all wounds with sterile dressings, including open fractures. Do not push bone ends back into the skin. Avoid excessive pressure on the wound. 7. Apply splint - Do not attempt to straighten borken bones.

8. Request medical assistance - All suspected fractures require professional medical treatment. Fracture of the Forearm There are two long bones in the forearm, the radius and the ulna. When both are broken, the arm usually appears to be deformed. When only one is broken, the other acts as a splint and the arm retains a more natural appearance. Fractures usually result in pain, tenderness, swelling, and loss of movement. In addition to the general procedures above, apply a pneumatic (air) splint if available; if not, apply two padded splints; one on the top (backhand side), and one on the bottom (palm side). Make sure the splints are long enough to extend from the elbow to the wrist. Once the forearm is sprinted, place the forearm across the chest. The palm of the hand should be turned in with the thumb pointing up. Support the forearm in this position (Fig. 6-2) with a wide sling and cravat bandage. The band should be raised about 4 inches above the level of the elbow.

Figure 6-2 - Sling Used to Support a Fractured Forearm Fracture of the Upper Arm There is one bone in the upper arm, the humerus. If the fracture is near the elbow, the arm is likely to be straight with no bend at the elbow. Fractures usually result in pain, tenderness, swelling, and loss of movement. In addition to the general procedures above, do the following: If the fracture is in the upper part of the arm, near the shoulder, place a pad or folded towel in the armpit, bandage the arm securely to the body, and support the forearm in a narrow sling. If the fracture is in the middle of the upper arm, you can use one well padded splint on the outside of the arm. The splint should extend from the shoulder to the elbow. Secure the arm firmly to the body and support the forearm in a sling (Fig. 6-3). If the fracture is at or near the elbow, the arm may be either bent or straight. Regardless what position you find the arm, do not attempt to straighten or move it. Gently splint the arm in the position in which you find it.

Figure 6-3 - Splint and Sling for a Fractured Upper Arm Fracture of the Rib Make the casualty as comfortable as possible so that the chances of further damage to the lungs, heart, or chest wall is minimized. A common finding in all casualties with fractured ribs is pain at the site of the fracture. Ask the casualty to point to the exact area of pain to assist you in determining the location of the fracture. Deep breathing, coughing, or movement is usually painful. The casualty should remain still and may lean toward the injured side, with a hand over the fracture to immobilize the chest and ease the pain. Simple rib fractures are not bound, strapped, or taped if the casualty is comfortable. If the casualty is more comfortable with the chest immobilized, use a sling and swathe (Fig. 6-4). Place the arm on the injured side against the chest, with the palm flat, thumb up, and the forearm raised to a 45-degree angle. Immobilize the chest, using wide strips of bandage (ace wrap) to secure the arm to the chest.

Figure 6-4 - Swathe Bandage for Fractured Rib Victim Fracture of the Thigh There is one long bone in the upper leg between the kneecap and the pelvis, the femur. When the femur is fractured, any attempt to move the leg results in a spasm of the muscles that causes severe pain. The leg is not stable, and there is complete loss of control below the fracture. The leg usually assumes an unnatural position, with the toes pointing outward. The injured leg is shorter than the uninjured one due to the pulling of the thigh muscles. Serious bleeding is a real danger since the broken bone may cut the large (femoral) artery. Shock usually is severe.

Figure 6-5 - Boards Used as Emergency Splint for Fractured Thigh In addition to the general procedures above, gently straighten the leg, apply two padded splints, one on the outside and inside of the injured leg. The outside splint should reach from the armpit to the foot, the inside splint from the groin to the foot. The splint should be secured in five places: (1) around the ankle, (2) over the knee, (3) just below the hip, (4) around the pelvis, and (5) just below the armpit (Fig. 6-5). The legs can then be tied together to support the injured leg. Do not move the casualty until the leg has been splinted. Fracture of the Lower Leg There are two long bones in the lower leg, the tibia and fibula. When both are broken, the leg usually appears to be deformed. When only one is broken, the other acts as a splint and the leg retains a more natural appearance. Fractures usually result in pain, tenderness, swelling, and loss of movement. A fracture just above the ankle is often mistaken for a sprain. In addition to the general procedures above, gently straighten the leg, apply a pneumatic (air) splint if available; if not, apply three padded splints, one on each side and underneath the leg. Place extra padding (Fig. 6-6) under the knee and just above the heel. The splint should be secured in four places: (1) just below the hip, (2) just above the knee, (3) just below the knee, and (4) just above the ankle. Do not place the straps over the area of the fracture. A pillow and two side splints also work well. Place a pillow beside the injured leg, then gently lift the leg and place it in the middle of the pillow. Bring the edges of the pillow around to the front of the leg and pin them together. Then place one splint on each side of the leg, over the pillow, and secure them in place with a bandage or tape. Fracture of the Kneecap The kneecap is also known as the patella. Although fractures of the kneecap do occur, the more common injuries are dislocations and sprains. In addition to the general procedures above, gently straighten the leg, apply a pneumatic (air) splint if available; if not, apply a padded board under the injured leg. The board should be at least 4 inches wide and should reach from the buttock to the heel. Place extra padding under the knee and just above the heel. The splint should be secured in four places: (1) just below the hip, (2) just above the knee, (3) just below the knee, and (4) just above the ankle. Do not place the straps directly over the kneecap.

Figure 6-6 - Immobilization of Fractured Kneecap Fracture of the Collarbone The collarbone is also known as the clavicle. When standing, the injured shoulder is lower, and the casualty is unable to raise the arm above the shoulder. The casualty attempts to support the shoulder by holding the elbow. This is the typical stance taken by a casualty with a broken collarbone. Since the collarbone lies near the surface of the skin, you may be able to see the point of fracture by the deformity and tenderness. In addition to the general procedures above, gently bend the casualty's arm and place the forearm across the chest. The palm of the hand should be turned in, with the thumb pointing up. Support the arm in this position (Fig. 6-7) with a wide sling. The hand should be raised about 4 inches above the level of the elbow. A wide roller bandage (or any wide strip of cloth) may be used to secure the casualty's arm to the body.

Figure 6-7 - Sling for Imobilizing Fractured Clavicle Fracture of the Jaw The lower jaw is also known as the mandible. The casualty may have difficulty breathing, difficulty in talking, chewing, and swallowing, and have pain of movement of the jaw. The teeth may be out of line, and the gums may bleed, and swelling may develop. The most important consideration is to maintain an adequate open airway. In addition to the general procedures above, apply a four-tailed bandage (Fig. 6-8), be sure the bandage pulls the lower jaw forward. Never apply a bandage that forces the jaw backward, since this may interfere with breathing. The bandage must be firm enough to support and immobilize the lower jaw, but it must not press against the casualty's throat. The casualty should have scissors or a knife to cut the bandage in case of vomiting.

Figure 6-8 - Four Tailed Bandage for a Fractured Jaw Fracture of the Skull The skull is also known as the cranium. The primary danger is that the brain may be damaged. Whether or not the skull is fractured is of secondary importance. The first aid procedures are the same in either case, and the primary intent is to prevent further damage. Some injuries that fracture the skull do not cause brain damage. But brain damage can result from minor injuries that do not cause damage to the skull. It is difficult to determine whether an injury has affected the brain, because symptoms of brain damage vary. A casualty who has suffered a head injury must be handled carefully and given immediate medical attention. Signs and symptoms that may indicate brain damage include:

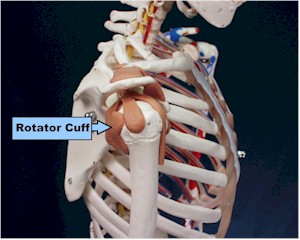

If you suspect a head injury, do the following: 1. Position the casualty flat, stabilize the head and neck as you found them by placing your hands on both sides of the head. 2. Establish and maintain an open airway - jaw-thrust maneuver. Note that the head is not tilted and the neck is not extended. Check the airway, breathing, and circulation (ABCs). 3. Finger sweep to remove any foreign bodies from the mouth. 4. Maintain neutral position of head and neck and, if possible, apply a cervical collar or improvised (towel) collar. 5. Apply dressing - Do not use direct pressure or tie knots over the wound. Apply ice or cold packs if available. (For blood or clear fluid from the nose or ears, cover loosely with a sterile dressing to absorb but not stop the flow). 6. Treat for shock - Casualties with suspected head and neck injuries are to remain flat. Do not raise the casualty's feet. If they are vomiting or bleeding around the mouth, place them on their side keeping the neck straight. Do not give anything to eat or drink. 7.Request medical assistance immediately - Time is critical. Head and neck injuries should be treated by professional medical personnel, if possible. Do not attempt procedures that you are not trained to do. Fracture of the Spine The spine is also known as the backbone or spinal column. If the spine is fractured, the spinal cord may be crushed, cut, or damaged so severely that death or paralysis may occur. If the fracture occurs in a way that the spinal cord is not damaged, there is a chance of complete recovery. Twisting or bending of the neck or back, whether due to the original injury or careless handling, is likely to cause irreparable damage. The primary symptoms of a fractured spine are pain, shock, and paralysis. Pain may be acute at the point of fracture and radiate to other parts of the body. Shock is usually severe, but the symptoms may be delayed. Paralysis occurs if the spinal cord is damaged. If the casualty cannot move the legs, the injury is probably in the back; if the arms and legs cannot move, the injury is probably in the neck. A casualty who has back or neck pain following an injury should be treated for a fractured spine. If you suspect a fractured spine, do the following: 1. Position the casualty flat, stabilize the head and neck as you found them by placing your hands on both sides of the head. 2. Establish and maintain an open airway - jaw-thrust maneuver. Note that the head is not tilted and the neck is not extended. Check the airway, breathing, and circulation (ABCs). 3. Finger sweep to remove any foreign bodies from the mouth. 4. Maintain neutral position of head and neck and, if possible, apply a cervical collar or improvised (towel) collar. 5. Keep the casualty comfortable and warm enough to maintain normal body temperature. 6. Treat for shock - Casualties with suspected spinal injuries are to remain flat. Do not raise the casualty's feet. If the casualty is vomiting or bleeding around the mouth, place them on their side keeping the neck straight. Do not give anything to eat or drink. 7. Request medical assistance immediately - Time is critical. Do not move the casualty unless it is absolutely necessary. Do not bend or twist the casualty's body. Do not move the head forward, backward, or sideways. Do not allow the casualty to sit up. Fracture of the Pelvis Fractures often result from falls, heavy blows, and crushing accidents. The greatest danger is damage to the organs that are enclosed by the pelvis. There is danger that the bladder will be ruptured or that severe internal bleeding may occur, due to the large blood vessels being torn by broken bone. The primary symptoms are severe pain, shock, and loss of the ability to use the lower part of the body. The casualty is unable to sit or stand and may feel like the body is "coming apart." Treat for shock, but do not raise the casualty's feet. Do not move the casualty unless absolutely necessary. Request medical assistance immediately. Dislocations A dislocation occurs when a bone is forcibly displaced from its joint. Many times the bone slips back into its normal position; other times, it becomes locked and remains dislocated until it is put back into place (reduction). Dislocations are caused by falls or blows and occasionally by violent muscular exertion. The joints that are most frequently dislocated are the shoulder, hip, finger, and jaw. A dislocation may bruise or tear muscles, ligaments, blood vessels, and tendons. The primary symptoms are rapid swelling, discoloration, loss of movement, pain, and shock. You should not attempt to reduce a dislocation. Unskilled attempts at reduction may cause damage to the nerves and blood vessels or may fracture a bone. You should leave this treatment to professional medical personnel and concentrate your efforts on making the casualty comfortable. If you suspect a dislocation, do the following: 1. Loosen clothing from around the injury. 2. Place the casualty in the most comfortable position. 3. Support the injured part with a sling, pillow, or splint. 4. Treat for shock. 5. Request medical assistance as soon as possible. Sprains A sprain is an injury to the ligaments that support a joint. It usually involves a sudden dislocation, with the bone slipping back into place on its own. Sprains are caused by the violent pulling or twisting of the joint beyond its normal limits of movement. The joints that are most frequently sprained are the ankle, wrist, knee, and finger. Tearing of the ligaments is the most serious aspect of a sprain, and there is a considerable amount of damage to the blood vessels. When the blood vessels are damaged, blood may escape into the joint, causing pain and swelling. If you suspect a sprain, do the following: 1. Splint to support the joint and put the ligaments at rest. Gently loosen the splint if it becomes so tight that it interferes with circulation. 2. Elevate & rest the joint to help reduce the pain and swelling. 3. Apply ice or cold packs, with cloth to prevent damage to the skin, the first 24 hours, then apply warm compresses to increase circulation. 4. Request medical assistance as soon as possible. Treat all sprains as fractures until ruled out by x-rays. Strains A strain is caused by the forcible over-stretching or tearing of a muscle or tendon. They are caused by lifting heavy loads, sudden or violent movements, or by any action that pulls the muscles beyond their normal limits. The primary symptoms are pain, lameness, stiffness, swelling, and discoloration. If you suspect a strain, do the following: 1. Elevate & rest the injured area to help reduce the pain and swelling. 2. Apply ice or cold packs, with cloth to prevent damage to the skin, the first 24 hours, then apply warm compresses to increase circulation. 3. Request medical assistance as soon as possible. Treat all strains as fractures until ruled out by x-rays. Contusions A contusion (bruise) is an injury that causes bleeding into or beneath the skin, but it does not break the skin. The primary symptoms are pain, tenderness, swelling, and discoloration. At first, the injured area is red due to local irritation; as time passes the characteristic "black and blue" (ecchymosis) mark appears. Several days after the injury, the skin becomes yellow or green in color. Usually, minor contusions do not require treatment. If you suspect a contusion, do the following: 1. Elevate & rest the injured area to help reduce the pain and swelling. 2. Apply ice or cold packs, with cloth to prevent damage to the skin, the first 24 hours, then apply warm compresses to increase circulation. 3. Request medical assistance as soon as possible. References 1. NAVEDTRA 10669-C, Hospital Corpsman 3 & 2

Department of the Navy Approved for public release; Distribution is unlimited. The listing of any non-Federal product in this CD is not an endorsement of the product itself, but simply an acknowledgement of the source. Operational Medicine 2001 Home · Military Medicine · Sick Call · Basic Exams · Medical Procedures · Lab and X-ray · The Pharmacy · The Library · Equipment · Patient Transport · Medical Force Protection · Operational Safety · Operational Settings · Special Operations · Humanitarian Missions · Instructions/Orders · Other Agencies · Video Gallery · Phone Consultation · Forms · Web Links · Acknowledgements · Help · Feedback

*This web version is provided by The Brookside Associates Medical Education Division. It contains original contents from the official US Navy NAVMED P-5139, but has been reformatted for web access and includes advertising and links that were not present in the original version. This web version has not been approved by the Department of the Navy or the Department of Defense. The presence of any advertising on these pages does not constitute an endorsement of that product or service by either the US Department of Defense or the Brookside Associates. The Brookside Associates is a private organization, not affiliated with the United States Department of Defense. |