|

Medical Education Division |

Operational Medicine 2001

Emergency War Surgery

Second United States Revision of The Emergency War Surgery NATO

Handbook

United States Department of Defense

Emergency War Surgery

Second United States Revision of The Emergency War Surgery NATO Handbook

United States Department of Defense

Home · Military Medicine · Sick Call · Basic Exams · Medical Procedures · Lab and X-ray · The Pharmacy · The Library · Equipment · Patient Transport · Medical Force Protection · Operational Safety · Operational Settings · Special Operations · Humanitarian Missions · Instructions/Orders · Other Agencies · Video Gallery · Phone Consultation · Forms · Web Links · Acknowledgements · Help · Feedback

|

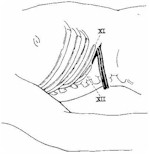

Emergency War Surgery NATO Handbook: Part IV: Regional Wounds and Injuries: Chapter XXIX: Wounds of the Abdomen Right Upper QuadrantUnited States Department of Defense Liver, Gallbladder, and Porta Hepatis Injuries to the liver are usually trivial, but they can be difficult, complex, and fatal. The major concern in the treatment of liver injuries is hemostasis. Simple lacerations or perforations through the periphery of the liver that have stopped bleeding require no specific therapy. The surgeon must obtain hemostasis when treating deeper wounds of the liver that continue to bleed. If possible, the surgeon should ligate all bleeding vessels. Adequate suction and exposure are essential. Two suction units should be used. The cautery, clips, and ligature are equally effective. The surgeon should perform resectional debridement of significantIy devitalized tissue. A formal hepatic lobectomy is never indicated. The Pringle maneuver, using a vascular clamp that will temporarily occlude the porta hepatis, might help control massive hemorrhage. This clamp may be applied for as long as 30 minutes with safety. The abdominal incision can be extended into the right chest to give better exposure of the retrohepatic cava or hepatic veins. Mobilization of the superior and anterior attachments of the liver allows mobilization of the organ. Only surgeons with personal experience in their use should consider using caval balloon catheters (Figure 33). Hypothermia and coagulopathy frequently develop in patients with massive liver injury and hemorrhage. The liver pack can be lifesaving for these patients. Large absorbent pads are placed under tension behind, above, below, and in front of the liver. This maneuver allows the surgeon to explore and repair other areas of the abdominal cavity. Then the wound can be closed by placing a series of large towel clips through the skin and fascia with the packs left in place. A dressing is applied, and the patient is returned to the recovery room where his temperature is brought to normal and lie is given appropriate blood component therapy and antibiotics. In 12-72 hours, the patient can be returned to the operating room where, under anesthesia, the abdomen is reopened, the packs are removed, and further hemostasis obtained if necessary. Frequently, bleeding will be found to have stopped. Injuries to the gallbladder should be treated by cholecystectomy, Injuries to the hepatic artery or the portal vein should be repaired, if possible. Injuries to the common bile duct should be repaired over a small T-tube with a closed suction drain placed adjacent to the repair. The tissue surrounding all but the most innocuous injuries to the liver should be drained by use of closed suction (Figure 34). Broad-spectrum antibiotics and blood component therapy to correct bleeding disorders should be given. Large mattress sutures in Glisson's capsule for deep liver injuries should not be used because hemobilia can develop later. A useful adjunct for hemostasis is the insertion of an intact vascularized pedicle of omentum into a liver injury with loose closure of the liver over the omentum. Duodenum and Pancreas Injuries to the duodenum are easily overlooked. The surgeon should suspect duodenal injury if missiles or missile tracks are found in the region of the duodenum, if there is blood in the nasogastric tube and retroperitoneum, or if there is air in the region of the duodenum. All patients who have had blunt trauma, and all patients who have had penetrating trauma in the region of the duodenum must have both a generous Kocher maneuver to expose the duodenum and an opening into the lesser sac that will expose the anterior pancreas and duodenal sweep. Minimal debridement and repair should be done for perforations, lacerations, and partial or complete transections. These patients need closed-suction drainage adjacent to, but not in contact with, the anastomosis. When more extensive injuries of the duodenum require more extensive debridement, the biliary, pancreatic, and gastric flow must be preserved. Missed injuries to the duodenum are often fatal. They may present late with signs of retroperitoneal abscess. Injuries to the pancreas always require drainage, generally closed-suction drainage. This may suffice for simple, superficial, blunt, or penetrating injuries of the pancreas, but deeper injuries, particularly those that involve the major pancreatic ducts, require more aggressive therapy. This may include resection of the distal pancreas. Transection or near-transection of the midbody of the pancreas can be treated by ligation of the distal end of the proximal duct and a Roux-en-Y anastomosis of the distal remnant into the gut. The choice to divert or resect the distal portion of the divided pancreas depends on the experience of the surgeon and the presence of associated injuries. If there is severe destruction of the head of the pancreas and duodenum, a pancreaticoduodenectomy may be required to save the patient. This situation is uncommon. Postoperatively, these patients frequently develop external fistulae. Closed-suction drain ensure that these fistulae are controlled. They may persist. The skin must be protected from the activated enzymes in the drainage. Fistula can lead to significant nursing problems. These can be limited by attention to details early.

Approved for public release; Distribution is unlimited. The listing of any non-Federal product in this CD is not an endorsement of the product itself, but simply an acknowledgement of the source. Operational Medicine 2001 Health Care in Military Settings

This web version is provided by The Brookside Associates Medical Education Division. It contains original contents from the official US Navy NAVMED P-5139, but has been reformatted for web access and includes advertising and links that were not present in the original version. This web version has not been approved by the Department of the Navy or the Department of Defense. The presence of any advertising on these pages does not constitute an endorsement of that product or service by either the US Department of Defense or the Brookside Associates. The Brookside Associates is a private organization, not affiliated with the United States Department of Defense. |