|

Medical Education Division |

Operational Medicine 2001

Emergency War Surgery

Second United States Revision of The Emergency War Surgery NATO

Handbook

United States Department of Defense

Emergency War Surgery

Second United States Revision of The Emergency War Surgery NATO Handbook

United States Department of Defense

Home · Military Medicine · Sick Call · Basic Exams · Medical Procedures · Lab and X-ray · The Pharmacy · The Library · Equipment · Patient Transport · Medical Force Protection · Operational Safety · Operational Settings · Special Operations · Humanitarian Missions · Instructions/Orders · Other Agencies · Video Gallery · Phone Consultation · Forms · Web Links · Acknowledgements · Help · Feedback

|

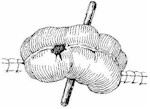

Emergency War Surgery NATO Handbook: Part IV: Regional Wounds and Injuries: Chapter XXIX: Wounds of the Abdomen MidabdomenUnited States Department of Defense Small Intestine Simple perforations, lacerations, or tears of the small intestine should be minimally debrided and closed primarily with a single layer of interrupted sutures (Figure 35). The surgeon must carefully search for multiple injuries by examining the small intestine in a systematic fashion, beginning at the ligament of Treitz and proceeding distally, looking at 10" segments of bowel on one side and then the other. The entire small bowel must be examined all the way to the cecum. The surgeon must carefully search for injuries to the mesentery at the edge of the bowel, since small tangential bowel perforations in the mesenteric surface may not be obvious on superficial examination. Use the "rule of twos" in treating penetrating injuries of the intestine and colon. Since fragments almost always perforate both walls of the intestine, they create an even number of injuries to the gut. Therefore, an even number of perforations can be expected. While this rule is not absolute, it is helpful in assuring that no injuries are missed. Rather than several individual repairs, a limited resection encompassing multiple injuries may be a safer and more expeditious approach in the patient with multiple injuries in close proximity. Injuries of the mesenteric vessels should be dealt with by ligation and bowel resection if there is nonviable or questionably viable bowel. Injuries to the aorta and inferior vena cava are usually fatal. Those who survive to reach the hospital frequently require urgent laparotomy as part of their resuscitation. These patients will frequently deteriorate during resuscitation and transfusion. They must be identified, explored, and hemostasis must be achieved, if they are to survive. An occasional patient with a severe splenic or hepatic injury can present in a similar fashion and require urgent operation for hemostasis. In this sort of case, continued transfusion and resuscitation in order to make the patient a better operative risk do not work, and death is the usual outcome. A senior surgeon must diligently search for these patients in the preoperative area and ensure early surgical intervention for hemostasis. The intraoperative management of these injuries includes generous incisions, the obtaining of adequate proximal and distal control and then appropriate repair of the injury. Frequently, minimal debridement and primary closure will suffice. Autogenous tissue (vein graft) is better than synthetic material in the repair of the more extensive vascular injuries, but suitable vein grafts may not always be available. Helpful maneuvers to achieve hemostasis in these patients include the insertion of a balloon catheter into the proximal and distal vessels through the injury site, use of a sponge stick to compress the aorta against the spine at the level of the diaphragm, and control of the aorta with a vascular clamp above the diaphragm via a limited thoracotomy. Ureters The ureters are infrequently injured. A ureteral injury usually causes hematuria. If this is noted preoperatively, an intravenous pyelogram will often provide a more secure diagnosis in these patients. Urine and blood will collect along the course of the ureter, particularly if there was a penetrating injury. These collections should prompt the surgeon to conduct a careful exploration of the entire course of the ureter. Ureteral injuries can be repaired with fine absorbable sutures and closed-suction drainage close to, but not touching, the repair. Internal stenting is not required in simple injuries. In more extensive injuries with significant tissue loss, repair will depend upon the location and extent of the injury and the experience of the surgeon. If the lower third of the ureter is injured, it may be reimplanted into the dome of the bladder through a muscular tunnel. The kidney can be mobilized, if necessary, to provide some additional length. Repairs should be done transversely or on a bias to maintain the diameter of the lumen since strictures may otherwise result. Drainage of all urinary repairs is required. Closed suction is preferred. Colon Injuries to the colon frequently result from penetrating abdominal injuries. The basic rule is that combat injuries of the colon ,hould not be closed. The majority of these patients should have either a loop colostomy which includes the injury, or resection of the injured colon and proximal diversion (Figure 36). Major injuries of the right colon should be treated by right hemicolectomy, with creation of a proximal ileostomy and distal mucus fistula (Figure 37). The reason for such a didactic approach is that these patients have an unprepared colon, usually have associated injuries, and it is unlikely that the operating surgeon will be able to follow the patient through the postoperative period. These particular lessons have been learned and relearned at great expense in previous conflicts. An option that is consistent with these guidelines is exteriorization of certain colon repairs. Injuries to the transverse and sigmoid colon may be repaired and then exteriorized in continuity for 6-10 days. If healing takes place, as is the case approximately 50% of the time, the repaired colon can be replaced into the abdomen at a second procedure. If the repair fails to heal, it can be converted to a loop colostomy with no particular danger to the patient. If this method is chosen, the opening in the abdominal wall must be large enough to allow for the stool to progress into the repaired segment and back to the abdomen. This opening will be larger than that needed for the usual loop colostomy. Failure to allow for this can result in the buildup of pressure in the repaired segment that will cause failure of the repair. Preoperative antibiotics are indicated when intestinal injuries are suspected; however, their postoperative use beyond 12 hours is questionable. As in suspected injuries of the small intestine, the surgeon must conduct a careful, methodical inspection of the colon from one end to the other. Again, it is appropriate to emphasize that injuries on the mesenteric surface of the colon are difficult to diagnose and must be searched for diligently, particularly in the presence of hematoma. Pelvis Injuries of the pelvis can be particularly difficult and frustrating. Hemorrhage from pelvic fractures or fragment injuries may not respond to the usual hemostatic techniques. A major advance in treatment of fracture dislocations of the pelvis associated with hemorrhage is the pelvic fixation device. This should be considered early in the management of these patients. Injuries of the bladder and rectosigmoid are easily overlooked. The surgeon must search for these carefully to avoid devastating complications. Rectum The surgeon' must suspect a rectal injury in any patient who has suffered a penetrating wound of the pelvis or in whom fragments could have traversed the pelvis. Anteroposterior and lateral roentgenograms, interpreted with the knowledge of entrance and exit wounds, are particularly helpful in determining if a rectal injury is likely to be present. Digital examination of the rectum is required. Endoscopy to determine the presence of intraluminal blood is indicated in these patients. Blood in the rectum should be assumed to be evidence of a transmural injury. A search for the specific location of the injury must be made. Rectal injuries are difficult to diagnose at the time of laparotomy. If no injury can be found in a patient with frank blood in the rectum, the surgeon must treat the patient as if a rectal injury has occurred. The treatment of patients with rectal injuries includes four components: first, a proximal, totally diverting colostomy; second, thorough cleansing and irrigation of the distal rectosigmoid; third, repair of the rectal tear, if accessible; and fourth, drainage of the presacral space with soft drains of the closed-suction type (Figure 38). Bladder Injuries of the bladder are usually associated with hematuria, The surgeon should suspect a bladder injury when the entrance or exit wound, the two-plane roentgenograms, or hematuria suggest that this is the case. A cystogram is the definitive test. It is obtained by the instillation of contrast into the bladder via an indwelling urethral catheter. Two roentgen views should be taken, one with the bladder full and the other after voiding. Extravasation indicates bladder perforation and requires operation. These injuries should be repaired with two layers of absorbable sutures, insertion of an indwelling suprapubic catheter, and placement of a soft closed-suction drain into the region of the repair. Bladder injuries will heal if the edges of the wound are approximated and adequate bladder decompression is maintained for ten days. Reproductive Organs Conservation should be practiced in the management of injuries of the reproductive organs. Penetrating or crush injuries of the labia, penis, scrotum, and testicles are best treated by conservative debridement and primary repair, if practical. The scrotum should be drained with a soft rubber drain. Injuries to the uterus, ovaries, and fallopian tubes will require conservative debridement and repair. Drainage is seldom indicated.

Approved for public release; Distribution is unlimited. The listing of any non-Federal product in this CD is not an endorsement of the product itself, but simply an acknowledgement of the source. Operational Medicine 2001 Health Care in Military Settings

This web version is provided by The Brookside Associates Medical Education Division. It contains original contents from the official US Navy NAVMED P-5139, but has been reformatted for web access and includes advertising and links that were not present in the original version. This web version has not been approved by the Department of the Navy or the Department of Defense. The presence of any advertising on these pages does not constitute an endorsement of that product or service by either the US Department of Defense or the Brookside Associates. The Brookside Associates is a private organization, not affiliated with the United States Department of Defense. |