|

Fetopelvic Disproportion

Clinical Pelvimetry

· X-ray Pelvimetry

· Estimation of Fetal Weight

· Progress of Labor

Fetopelvic disproportion is any clinically significant mismatch between

the size or shape of the presenting part of the fetus and the size or

shape of the maternal pelvis and soft tissue. A 12-pound fetus trying to

squeeze through a maternal pelvis that is only adequate for a 7-pound

baby would be an example of fetopelvic disproportion.

The problem of

disproportion may be based strictly on size, or may be related to the

way in which the fetus is trying come out. Occiput anterior is the usual

position for a fetus and that position is generally the most favorable

for negotiating the diameters and turns of the birth canal. Should a

fetus attempt to come through the birth canal in the occiput posterior

position, it is more difficult for the fetal head to negotiate the

turns. If the fetus is small enough and the pelvis large enough, it can

still deliver as a posterior. Otherwise, the fetal head will need to be

turned to anterior, or a cesarean section performed.

Some disproportions are relative, while others are absolute. The

relative disproportions may allow for non-operative vaginal delivery, if

labor is allowed to continue long enough and there is sufficient molding

or re-shaping of the fetal head to allow it to squeeze through. In the

case of absolute disproportion, no amount of fetal head re-shaping will

allow for unassisted vaginal delivery, and it may not allow for a

vaginal delivery at all. Even in the case of relative disproportion,

that fact that eventually a fetus might squeeze through doesn't

necessarily mean that continued labor is wise.

Even if highly accurate measurements of the maternal pelvis and fetal

size were possible (and they are not), it would still be difficult to

predict in advance those who will deliver vaginally easily and those who

will not. All measurements are essentially static, and do not take into

account the inherent "stretchiness" of the maternal pelvis or the

compressibility of the fetus. The pelvis is not a single solid bone, but

is comprised of many bones, held together by cartilage and ligaments.

During pregnancy, these soft-tissue attachments become more pliable and

elastic, allowing considerable movement. Similarly, fetal tissues can be

safely compressed, to a certain extent. For these reasons, trying to

predict whether a dynamically-shaped fetus will fit through a

dynamically-shaped pelvis, based only on static measurements, becomes

nearly impossible. Can a basketball fit through a rubber band? Of

course, it depends on how big the basketball is, how big the rubber band

is, how inflated the basketball is, and how stretchy the rubber band is.

Accurately measuring the size of the basketball and the rubber band

won't answer all of those questions.

Clinical Pelvimetry

Methods of performing clinical pelvimetry range from the very simple

to very complex. Simple digital evaluation of the pelvis, allows the

examiner to categorize it as probably adequate for an average sized

baby, borderline, or contracted. Other methods include the following:

-

Measuring the diagonal conjugate. Insert two fingers into the

vagina until they reach the sacral promontory. The distance from the

sacral promontory to the exterior portion of the symphysis is the

diagonal conjugate and should be greater than 11.5 cm.

-

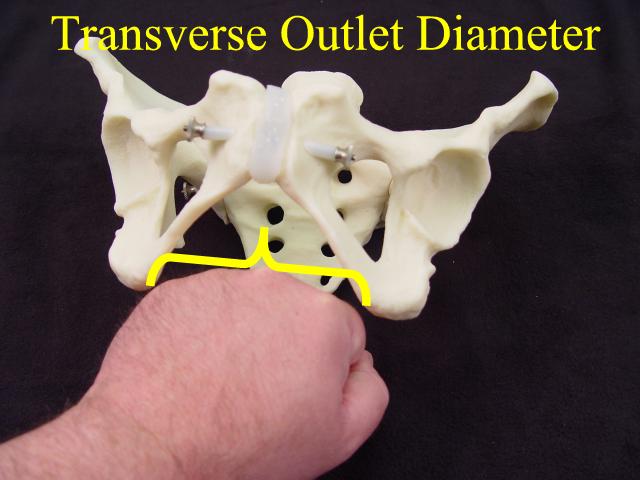

Measure the bony outlet by pressing your closed fist against the

perineum. Compare the previously-measured diameter of your fist to the

palpable distance between the ischial tuberosities. Greater than 8 cm

bituberous (or bi-ischial, or transverse outlet) is considered normal.

-

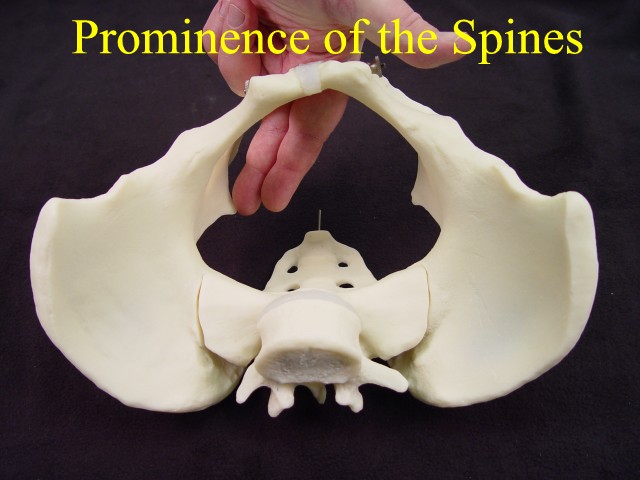

Feel the ischial spines for their relative prominence or flatness.

Spinal prominence narrows the transverse diameter of the pelvis.

-

Feel the pelvic sidewalls to determine whether they are parallel

(OK), diverging (even better), or converging (bad). True outlet

obstruction is fortunately rare.

X-ray Pelvimetry

This technique is primarily of historical interest. It was believed in

the past that accurate x-ray measurements of the pelvis would allow for

identification of those patients who would have disproportion. X-ray

pelvimetry (or CT pelvimetry) allows for reasonably accurate measures of

various internal measurements not available to clinical examination.

Among these ate the true obstetrical conjugate, transverse diameter of

the inlet, and bispinous diameter (transverse diameter of the midpelvis)..

In numerous studies since then, the usefulness of x-ray pelvimetry

has been discredited to the point that x-ray pelvimetry is rarely

performed today. The problem is not that the internal measurements

cannot be assessed with reasonable accuracy, but that the measurements

rarely have any clinical meaning. Vaginal delivery may still occur (and

usually does) despite small measurements. Cesarean section may still be

needed even if the internal measurements look acceptable. Finally, the

most contracted of pelvises can usually be defined on clinical

examination alone.

Occasionally, x-ray pelvimetry is still used. One example could be a

maternal history of pelvic deformity where the wisdom of allowing a

vaginal trial of labor is in question.

Estimation of Fetal Weight

Estimates of pelvic capacity and shape are only half of the fetopelvic

disproportion evaluation. The other half is the estimate of fetal size.

Estimates can be made by feeling the mother's abdomen, by ultrasound

scan estimates, or by asking the mother how big she believes the fetus

is.

Ultrasound estimates of fetal weight are based on formulas that

weigh various fetal dimensions (biparietal diameter, abdominal

circumference, femur length, etc.), then apply mathematical modeling to

come up with an estimated fetal weight. Ultrasound estimates are

considered by many to be the most accurate means of predicting fetal

weight. Accuracy of ultrasound varies, but its predictions generally

come within 10% of the actual birthweight two-thirds of the time, and

within 20% of the actual birthweight in 95% of cases. That means that if

ultrasound predicts and average-sized, 7 1/2 pound baby, that most of

the time (95% of the time), the baby will weigh somewhere between 6

pounds and 9 pounds, and occasionally (5% of the time), the baby will

weigh less than 6 pounds or more than 9 pounds. We would all prefer that

ultrasound be more consistently reliable in its estimates of fetal

weight. Ultrasound estimates of fetal weight are based on formulas that

weigh various fetal dimensions (biparietal diameter, abdominal

circumference, femur length, etc.), then apply mathematical modeling to

come up with an estimated fetal weight. Ultrasound estimates are

considered by many to be the most accurate means of predicting fetal

weight. Accuracy of ultrasound varies, but its predictions generally

come within 10% of the actual birthweight two-thirds of the time, and

within 20% of the actual birthweight in 95% of cases. That means that if

ultrasound predicts and average-sized, 7 1/2 pound baby, that most of

the time (95% of the time), the baby will weigh somewhere between 6

pounds and 9 pounds, and occasionally (5% of the time), the baby will

weigh less than 6 pounds or more than 9 pounds. We would all prefer that

ultrasound be more consistently reliable in its estimates of fetal

weight.

Clinical estimates by an experienced examiner, based on feeling the

mother's abdomen, are, in some studies, just as accurate as ultrasound

(in other words, somewhat reliable). Interestingly, some studies also

demonstrate that the mother's guess about her own baby's size is also

about as accurate as ultrasound, if she has delivered a baby in the

past. If she hasn't, then her estimates are less accurate.

Progress of Labor Progress of Labor

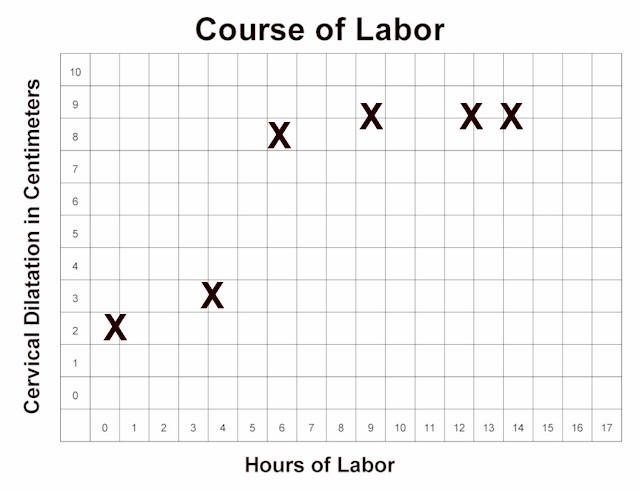

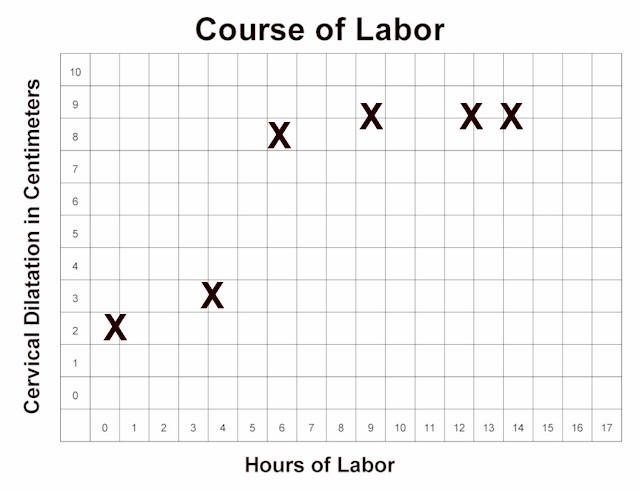

Monitoring the progress of labor is another technique that is used to

assess the presence or absence of fetopelvic disproportion. This

technique hinges on the belief that if the fetus is too big to come

through, there will be an arrest of progress of labor. After confirming

that the arrest is not due to other factors (inadquate contractions, for

example), and allowing adequate time for the arrest to resolve,

fetopelvic disproportion is presumed to be present and operative

delivery (usually cesarean section) is undertaken. Many physicians use a

"2-hour rule," depending on the clinical circumstances, to allow for

active labor to show advancement before resorting to cesarean section.

Others have different time frames in mind.

|