Arrest of Active Labor

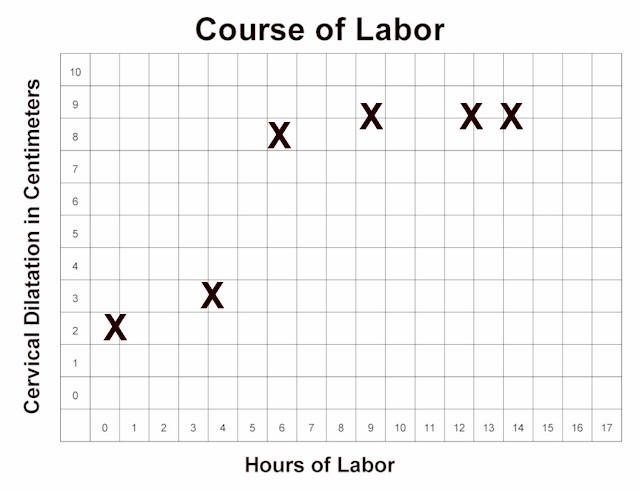

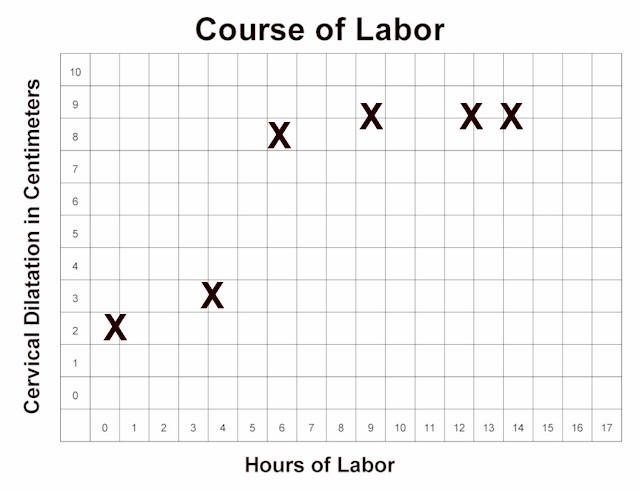

Normal labor progresses slowly

during the latent phase. Then, after 4 cm dilatation, the more rapid,

active phase of labor begins.

During active labor (after 4 cm), the

cervix should progressively dilate at a rate of no less than 1.2 cm/hour (for first babies) to 1.5

cm/hour (for subsequent babies). If active labor progresses more slowly than this, an

"arrest of labor" has occurred.

The arrest of labor may be simple slowing of the labor below the expected rate, or may

represent a complete arrest, in which there is no further progress for at least 2 hours.

There are essentially only two causes for an arrest of labor in the

active phase:

Contractions may be inadequate because they are too infrequent (more than 4 minute

intervals), or do not last long enough (less than 30 seconds). Typically,

they are neither frequent enough nor long enough.

Mechanical impediments to labor may include:

-

Absolute feto-pelvic disproportion, in which the maternal pelvis is not large enough to

allow the baby to pass through the birth canal.

-

Relative feto-pelvic disproportion, in which there is a snug fit, but given time and

adequate contractions, the baby can safely negotiate the birth canal

-

Fetal malposition, in which the fetal head is presenting in a less favorable position

(for example, occiput posterior, or with fetal hand preceding the head, or a transverse

lie)

-

Asynclitism, in which the fetal head is angled slightly to one side, making it more

difficult for a clear passage through the birth canal.

Inadequate contractions are treated with uterine stimulation. This is generally

accomplished with intravenous oxytocin, delivered in steady, small amounts with a

controlled infusion pump. The dose is started relatively low, and then advanced gradually

until the desired effect is achieved. Later in labor, the dosage is often adjusted

downward or stopped altogether if the contractions are too close together (consistently

more than 5 contractions every 10 minutes).

In far forward military settings, a controlled infusion pump may not be

available. In such cases, some low-tech approaches may be useful:

-

Nipple stimulation (rolling the nipple back and forth with thumb and forefinger) will

cause of release of the mother's own oxytocin from her pituitary gland. This will have the

effect of stimulating contractions. Stimulating both nipples will have about double the

effect as stimulating one nipple. After about 15-20 minutes of nipple stimulation you will

have released about as much natural oxytocin as is available. Nipple stimulation can be

repeated at a later time, after the natural oxytocin supply has been replenished.

-

While this technique can be effective, the biggest problem is overstimulation of the

uterus because of too much oxytocin. Rather than achieving more

frequent, longer contractions, you will end up with a single, 3-5 minute

contraction that is threatening to the fetus and the integrity of the

uterus.

-

Start with stimulation of just one nipple. Have the mother perform this on herself. It

usually takes 3-5 minutes of this before you will notice any effect on the uterus. If

gentle nipple stimulation is not effective, increase the strength of the nipple massage.

If there is still no result, you can try stimulating both nipples. Just make sure to give

the uterus enough time to respond.

-

Amniotomy (artificial rupture of the bag of waters) can also be a

effective stimulus to labor. Amniotomy may be safely performed if the fetal

head is sufficiently engaged in the maternal pelvis to keep the umbilical cord

from slipping past it, creating a prolapsed cord situation.

-

Open drip oxytocin, largely abandoned in the United States 30 years

ago for safety reasons, can still be effectively employed, if you are very

careful with it.

-

Put 10 units (1 amp) of oxytocin in 1 Liter of IV fluid (NS, LR,

D5W, etc.) and mix it well.

-

Piggyback the oxytocin solution into a mainline IV (of any type),

running at 100-125 cc per hour.

-

While monitoring the uterine contractions (with electronic fetal

monitoring, if available, or with your hand on the mother's abdomen if

EFM is not available), open the oxytocin IV just enough to allow 3 drops

to enter the mainline.

-

Wait a few minutes to assess the impact of these 3 drops.

-

If there is no measurable impact after a few minutes, then allow

several more drops to infuse. Keep you hand on the patient's abdomen so

that you can monitor the contractions.

-

Gradually increase the oxytocin flow rate until you achieve regular

uterine contractions every 2.5 to 3 minutes, lasting about 60 seconds.

While increasing the flow rate, allow several minutes after each change

in rate to evaluate the impact on uterine contractions.

-

If the contractions last longer than 60 seconds, slow or stop the

oxytocin.

-

If the contractions consistently occur more often than every 2

minutes, slow or stop the oxytocin.

-

If the patient experiences uterine tetany (continuous contractions),

stop the oxytocin.

-

The fetal heart should be monitored during this time, preferably

with EFM, but listening to the rate every 15 minutes can also be

effective.

-

Open drip oxytocin is considered more dangerous than when used with

a controlled infusion pump because:

-

It is easier for the oxytocin flow to increase suddenly, causing

too many contractions and stresses on the uterus.

-

There is greater risk of uterine rupture without the constant

controlled flow of an infusion pump.

-

In the end, so long as you monitor the patient and provide a

reasonably controlled, steady but titratable delivery of dilute

oxytocin, you will be helpful to those who need oxytocin

stimulation but were unfortunate enough to be in a location that does

not have all of the safety features found in the Continental United

States.

Normal Labor

Arrest of Active Labor |

The possibility of a mechanical impediment should be considered whenever arrest

disorders occur.

-

If the fetus is in a transverse lie, it will not be able to deliver vaginally and

continuing labor will ultimately lead to uterine rupture.

-

If the fetus is in an occiput posterior position, vaginal delivery may still be

successful, but it will take longer.

-

If the fetus is a little large for the birth canal, vaginal delivery may still be

successful, but only with time and fetal molding to the shape of the pelvis.

-

If there is a compound presentation (head and hand, for example), the baby may still

come through, but it may take much longer. (Try pinching the hand to see if the fetus will

react by pulling it up and out of the way.)

Usually, there is no way to know in advance which labors will experience an absolute

obstruction and those that will not. For this reason, a trial of labor is almost always

indicated. Those patients with an absolute obstruction will demonstrate a complete arrest

pattern and will need cesarean section.

|