LESSON OBJECTIVES

4-1. Identify terms and definitions that are related to postoperative nursing.

4-2. Identify effects of anesthesia during the postoperative phase.

4-3. Identify the possible negative effects of surgery on the integumentary system.

4-4. Identify the types of wound healing during the postoperative phase.

4-5. Identify the factors that may impair wound healing.

4-6. Identify facts related to wound drains.

4-7. Identify nursing implications according to body systems as they are related to the care of a patient postoperatively.

4-8. Identify nursing implications that are related to the care of a postoperative patient in general.

4-1. OVERVIEW

Many of the aspects of nursing care during the recovery from the initial effects of anesthesia are carried over into the postoperative phase. In postoperative nursing, the helping and caring aspects of nursing become dramatically clear. The patient recovering from spinal anesthesia is unable to turn himself, so the nurse turns him frequently. The unconscious patient is unable to control the secretions trickling down his throat, so the nurse controls them by positioning and by suctioning. In helping the patient, the nurse is guided by the doctor’s orders for postoperative treatment and therapy. However, the helping aspect of nursing is evident even as the nurse bathes perspiration from the patient’s forehead or adjusts the light so that it does not shine directly in his eyes.

The helplessness of the postoperative patient makes it essential that practical nurses have the skills and knowledge to help maintain the life processes, provide safety and comfort, and prevent complications. Postoperative care mainly takes place in the patient’s room in the hospital.

4-2. TERMS AND DEFINITIONS

Although only a few terms and definitions are listed below, more terms and definitions will be dispersed throughout the lesson.

a. Atelectasis. Collapse of the lungs.

b. Distention. The state of being stretched out or bloated, as the abdominal cavity may be with gas or fluid.

c. Exudate. Fluid, usually containing pus, bacteria, or dead cells.

d. Flatus. Digestive tract gas that is expelled rectally (expelling gas orally is called burping or eructating).

e. Nasogastric Tube. A rubber or plastic tube that is inserted through the nose (naso) and extending into the stomach (gastric).

f. Peristalsis. The involuntary, wavelike motion of the digestive tract that moves food through the alimentary canal.

4-3. GENERAL

The physiological needs of the postoperative surgical patient are of paramount importance. Once these needs are met, his psychological and social needs can be met. The effects of anesthesia tend to last well into the postoperative phase and affect the respiratory, cardiovascular, urinary, and gastrointestinal systems.

4-4. RESPIRATORY SYSTEM

Anesthesia can cause a patient’s pulmonary efficiency to decrease, thereby causing an increase in the probability of postoperative pneumonia. We all must breathe and take in sufficient oxygen in order to live. Respiratory function, or breathing, is often compromised in the surgical patient. The combination of drugs given to produce anesthesia or to reduce pain, as well as the body’s response to the trauma of surgery itself, will affect the respiratory function.

4-5. CARDIOVASCULAR SYSTEM

Certain anesthetic agents can increase the probability of cardiac problems and postoperative hypotension. Common circulatory problems include hemorrhage and shock, cardiac arrest, and postoperative hypotension. Disruption of sutures and insecure ligation of blood vessels can cause hemorrhage. Shock occurs as a result of hemorrhage or cardiac insufficiency.

4-6. URINARY SYSTEM

Anesthesia can cause urinary retention. This is not an uncommon complication since anesthesia temporarily depresses urinary bladder tone. A decrease in fluid intake can lead to dehydration and infection.

4-7. GASTROINTESTINAL SYSTEM

Anesthesia slows or stops the peristaltic action of the intestine, which results in constipation. Nausea and vomiting may cause fluid imbalance. Abdominal distention/flatus may also be present.

EFFECTS OF SURGERY ON THE INTEGUMENTARY SYSTEM

4-8. GENERAL

When wounds occur, a variety of effects may result, such as immediate loss of all or part of organ functioning, sympathetic stress response, hemorrhage and blood clotting, bacterial contamination, and death of cells. Careful asepsis is the most important factor in keeping these effects to a minimum and promoting the successful care of wounds.

4-9. POSSIBLE NEGATIVE EFFECTS

a. Wound Infection. The first sign of wound infection is increased pain in the incision. The incision shows signs of infection by becoming reddened, warm, and swollen and by draining pus-like material. If a patient develops a wound infection, it is important to prevent it from spreading to other patients.

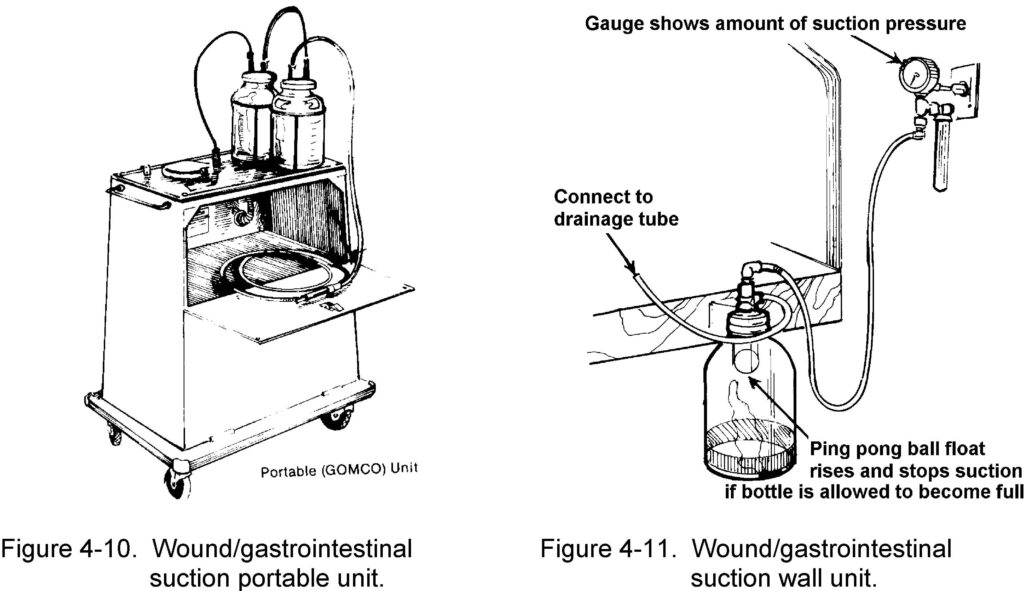

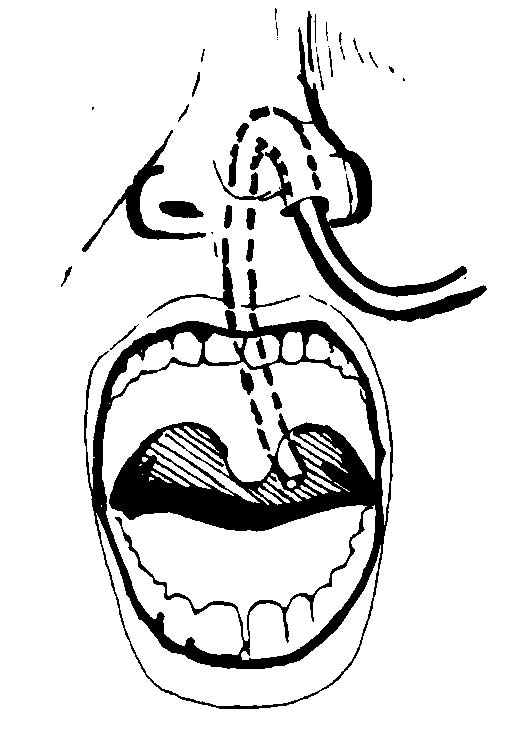

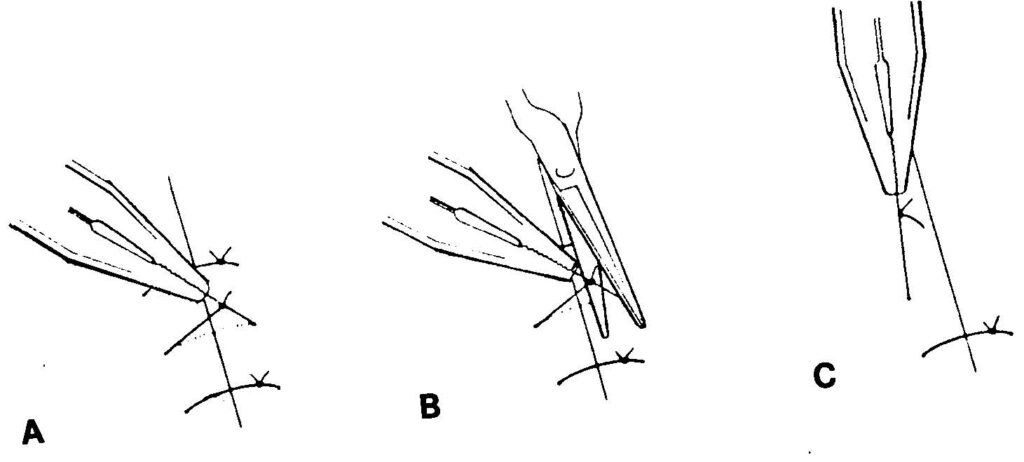

b. Wound Separations. This is the breaking apart of the edges of the incision. The causes of wound separation are malnutrition (which interferes with the normal healing process), defective suturing, infection, and excessive strain on the wound from retching, coughing, etc. Dehiscence and evisceration are two types of wound separations (see Figure 4-1).

(1) Dehiscence. This is the separation (opening) of the wound edges without the protrusion of organs. Small openings are not unusual and may be closed or supported with sterile tape. The openings always need to be supported and the wound observed regularly for further openings.

(2) Evisceration. This is the separation of the wound edges with the protrusion of organs. This rarely happens, but it is a serious complication when it does happen. The patient is usually taken to surgery immediately for resuturing.

4-10. TYPES OF WOUND HEALING

One of the most fundamental and marvelous defensive properties of living organisms is the power to heal wounds. The reaction of tissues to a surgical incision differs only in degree from that caused by a laceration (usually occurring in accidents). There are always bacteria on the skin that are carried into deeper tissues, even when the wound is a surgical incision. Clean wound healing is an intricate, exact biological process. The two types of wound healing discussed in this subcourse are primary and secondary.

a. Primary. This is a form of connective tissue repair that involves the proliferation of fibroblasts and capillary buds and the subsequent laying down of collagen to produce a scar.

b. Secondary. This is healing of an open wound where there has been a significant loss of tissue. The defect must be filled by a slow buildup of new connective tissue. This process results in a large scar formation.

4-11. FACTORS WHICH MAY IMPAIR WOUND HEALING

The following factors may impair wound healing.

a. Inadequate nutrition.

b. Hypoproteinemia and vitamin C deficiency.

c. Anemia.

d. Diminished blood supply to the area.

e. Steroid administration (cortisone inhibits subsequent fibroplasia and collagen formation).

f. Obesity.

g. Diabetes mellitus.

h. Debilitating diseases, such as cancer.

i. Infection.

4-12. FACTS ABOUT WOUND DRAINS

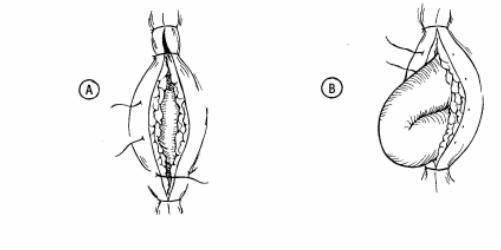

a. The technique of using drains, tubes, and catheters at the wound site may be necessary to promote healing by permitting fluid to be removed from the surgical site. This technique is often used to drain abscesses and intestinal contents when leakage may occur.

b. The Penrose drain is the most common type of drainage system used. It is made of soft rubber and causes little tissue reaction. It is sutured to the skin and a safety pin is placed externally to maintain its position. The Penrose drain acts by drawing any pus or fluid along its surfaces through a stab wound adjacent to the main incision. See Figure 4-2 for a Penrose drain.

NURSING IMPLICATIONS BY BODY SYSTEMS OF A POSTOPERATIVE PATIENT

4-13. RESPIRATORY SYSTEM

Postoperative nursing intervention to meet respiratory needs is chiefly designed to prevent respiratory complication. Nursing actions include checking the patient’s respiratory rate, depth, and rhythm as ordered or according to local policy or whenever vital signs are taken. Being alert to signs of respiratory problems cannot be over emphasized. Measures for encouraging lung expansion and exchange of gas are given below.

a. Reteach the patient coughing and deep breathing exercises (refer to Lesson 1, paras 1-5a(2) and (3)). Coughing is encouraged to dislodge mucous plugs. Deep breathing helps to maximize voluntary lung expansion. Record the procedure and report significant observations to the Charge Nurse. Include the time of procedure, sputum (if present — color, odor, amount), and patient’s tolerance.

b. Turn the patient as ordered (refer to Lesson 1, para 1-5a(1)). Turning the patient allows alternating maximum expansion of the uppermost lung.

c. Ambulate the patient as ordered. If the patient cannot ambulate, periodically assist him to a sitting position in bed if allowed. This position permits the greatest lung expansion. Ambulation promotes deep breathing.

d. Position the patient in a Fowler’s position to facilitate lung expansion, if permitted.

4-14. CARDIOVASCULAR SYSTEM

Nursing measures to meet the patient’s circulatory needs are provided to prevent thrombophlebitis.

a. Reteach lower extremity exercises while the patient is on bedrest (refer to Lesson 1, para 1-5a(4)).

b. Ambulate the patient, as ordered.

(1) Provide physical support for first attempts.

(2) Have patient dangle feet at bedside before ambulation.

(3) Monitor patient’s blood pressure while he dangles.

NOTE: Do not ambulate patient if he is hypotensive when dangling. Report this event to the Charge Nurse.

4-15. URINARY SYSTEM

As previously mentioned, anesthetics temporarily depress urinary bladder tone. Urinary bladder tone usually returns within six to eight hours after surgery. The length of time a patient may be permitted to go without voiding after surgery varies considerably with the type of surgery performed. However, in the mean time, nursing responsibilities in relation to urinary elimination are those listed below.

a. Report to the Charge Nurse if the patient without a Foley catheter has not voided within eight hours of return to ward from the recovery room.

(1) Patients who have had abdominal surgery, particularly if in the lower abdominal and pelvic regions, often have difficulty voiding after surgery.

(2) Operative trauma in the region near the bladder may temporarily decrease the sensation of needing to void (urinate).

(3) The fear of pain may cause tenseness and difficulty in voiding.

b. Palpate patient’s bladder for distention and assess patient’s response.

(1) The patient will tell you if he has to void (he will feel a sense of fullness and urgency).

(2) Report this event to the Charge Nurse.

c. Assist the patient to void.

(1) Position the patient comfortably on bedpan, with urinal, or in bathroom.

(2) Provide the patient with privacy.

d. Measure and record the patient’s urinary output.

e. Notify the Charge Nurse if less than 30 cc of urine is voided during first experience after surgery.

f. Report to the Charge Nurse if the patient complains of bleeding when voiding or urine shows blood.

g. Follow ward infection control SOP for care of a patient with a Foley catheter.

4-16. GASTROINTESTINAL SYSTEM

a. Normal Function of the Gastrointestinal System. Regaining normal function of the gastrointestinal system as soon as possible is very important. The following nursing implications also apply to the patient who has had abdominal surgery.

(1) Report to the Charge Nurse if the patient complains of abdominal distention.

(2) Ask the patient if he has “passed gas” within 24 hours of return to the ward from the recovery room.

(3) Auscultate for bowel sounds and report assessment to the Charge Nurse.

(4) Provide the patient with a quiet environment in a private bathroom so he feels comfortable expelling flatus.

(5) Encourage the patient to take warm or hot liquids and solids rather than cold, if he is not NPO. Warm or hot liquids help to reduce distention.

(6) Ambulate the patient to assist peristalsis.

(7) Administer medications or enema as ordered by the physician if nursing measures are not effective in relieving abdominal distention. Both treatments will facilitate peristalsis and relieve distention.

(8) Tell the patient to report his first postoperative bowel movement to you.

(9) Record patient’s bowel movement on Intake and Output (I & O) Work Sheet.

(10) Document nursing measures and results in the Nurse’s Notes.

NOTE: Last measures to reduce abdominal distention may require the insertion of a nasogastric (N/G) tube or use of a rectal tube.

b. Nasogastric Tube. The procedures to insert a nasogastric tube to administer intestinal decompression therapy to a postoperative patient are given below.

(1) Wash your hands and assemble all needed equipment.

(a) NG (Levin) tube.

(b) Irrigating set which includes: a basin, lubricant (water-soluble), towel, solution container, irrigating syringe, and protector cap or tube plug.

(c) Tape.

(d) Tissues.

(e) Stethoscope.

(f) Glass of water and straw.

(g) Nasogastric suction apparatus (as needed).

(2) Identify and approach the patient, explain what you are going to do, and gain his cooperation.

(3) Provide for patient’s privacy.

(4) Position the patient.

(a) The Fowler’s position is usually assumed because it enables the tube to move by gravity down the digestive tract.

(b) Hand the emesis basin and the tissues to the patient or place the emesis basin close beside the patient’s face with the tissues near the pillow.

(5) Check the airflow through the patient’s nostril.

(a) Close one side of the patient’s nose and check the airflow through the other.

(b) Pass the tube through the nostril with the best airflow.

(c) If changing the NG (Levin) tube, insert it in the nostril other than the one previously used to avoid further irritation of the tissue.

(6) Measure the tube for distance to be inserted.

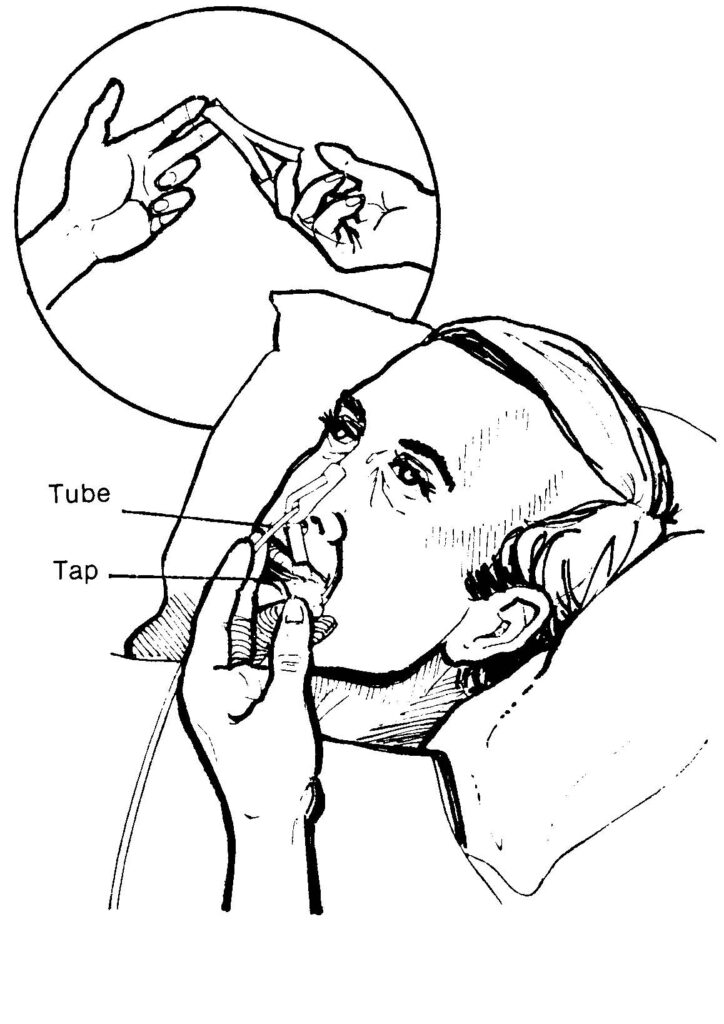

(a) Find the target distance for inserting the tube by measuring from the tip of the nose to the tip of the ear, and then to the tip of the xiphoid process (see Figure 4-3. Mark it with a small piece of tape.

(b) A scale (commercial) is available that measures the distance more precisely since NEX may be too long for short patients and too short for taller adults.

(c) Some tubes have approximate target marking on them.

1 One black band indicating the length of the tubing needed to reach the stomach.

2 Two bands for the pylorus.

3 Three bands for the duodenum.

(7) Lubricate the tip of the tube and insert it in the patient’s nose.

(a) Aim the tube down and toward the ear.

(b) For easier insertion, use water or a water-base lubricant to moisten the tip of the tube.

(c) Do not use an oil-base lubricant. The possibility of lipoid (fat) aspirational pneumonia is to be avoided.

(d) If you encounter a severe resistance, withdraw the tube and insert it in the other nostril.

(e) Do not forcibly push it because you could injure tissues and cause bleeding.

(8) Have the patient drop his head forward and begin to swallow as the tube reaches the back of the throat.

(a) Tell the patient to bend his head forward and (if permitted) to swallow sips of water as the tube is passed down the esophagus to the stomach.

(b) Check the position of the tube as it passes down the back of the patient’s throat by having the patient open his mouth. Hold down the patient’s tongue with a tongue depressor.

(c) Withdraw the tube into the nose and begin again by having the patient bend head forward and swallow; restart if the tube is coiled up in his mouth.

(d) Avoid long waits (long delays can increase the patient’s anxiety/discomfort). However, the patient can signal you to stop for a moment to rest, if necessary.

(9) Advance the tube each time the patient swallows or sucks air. See Figure 4-4.

(a) If permitted, continue to have the patient swallow water or ice. This helps as the tube is passed.

(b) The esophageal peristalsis and the fact that you work in a reassuring manner will help the patient tolerate the procedure.

(10) Check the placement of the tube.

(a) When the target point on the tube has reached the nose, the tube should be in the stomach.

(b) Verify placement by one of the following methods:

1 The return of gastric juices is an obvious sign. Use the irrigating syringe to pull back using gentle suction and aspirate the stomach contents. If none are obtained, turn the patient onto his left side, insert the tube another one or two inches, and try again.

2 Inject 10 to 20 ml of air into the tube with the irrigating syringe and listen with the stethoscope placed to the left of the xiphoid. The air will make a swishing sound as it enters the stomach. The patient may belch if the tube is in the esophagus.

(c) If the patient has dyspnea, coughing, or cyanosis or is unable to talk or hum, the tube is in the trachea and must be immediately removed and reinserted.

(11) Tape the tube securely to the face, avoiding pressure caused by the tube against the nasal tissues (see Figure 4-5).

(12) As ordered, attach the free end of the tube to the suction machine.

(a) Make sure the machine is plugged in and turned on low pressure.

(b) If suction has not been ordered, clamp, plug, or cover the end of the NG (Levin) tube so that is will not leak gastric contents.

(c) When the patient is allowed out of bed, loosely loop the tubing in a circle, secure it with adhesive tape, and pin to the patient’s gown.

(d) This will help prevent pulling that would be uncomfortable to the patient as well as tube dislodgement.

(13) Provide for the patient’s comfort.

(14) Remove used articles and leave bedside unit neat and tidy.

(15) Record procedure and report significant observations to the Charge Nurse.

c. Rectal Tube. The procedures for using a rectal tube to administer intestinal decompression therapy to a postoperative patient are as follow.

(1) Wash hands and assemble all equipment.

(a) Rectal tube with attached vented bag (22 to 24 Fr).

(b) Water-soluble lubricant.

(c) Chux (R).

(d) Exam gloves.

(e) Wash cloth and towel.

(2) Verify the physician’s order.

(3) Identify and approach the patient, explain what you are going to do, and gain his cooperation.

(4) Provide for patient’s privacy.

(5) Assist the patient to a left side-lying position with knees slightly flexed.

(6) Place the Chux (R) under the patient’s buttocks.

(7) Cover the patient with a sheet.

(8) Wash your hands.

(9) Put on exam gloves.

(10) Lubricate the tip of the rectal tube with water-soluble lubricant.

(11) Separate the patient’s buttocks and gently insert the tip of the tube 3 to 5 inches into the rectum. See Figure 4-6. DO NOT FORCE THE TUBE.

(12) Remove the exam gloves.

(13) Leave the tube in place for 20 minutes or as ordered by the physician.

(14) Remove the tube after the prescribed time.

(15) Wash and dry the anal area.

(16) Position the patient comfortably.

(17) Observe the bag for inflation.

(18) Discard equipment or return it to the appropriate location.

(19) Wash your hands.

(20) Record procedures and report significant observations to the Charge Nurse.

(a) Time the rectal tube was inserted and removed.

(b) The patient’s reaction to the procedure; if he feels less full.

(c) All patient teaching done and the patient’s apparent level of understanding.

4-17. INTEGUMENTARY SYSTEM

Being knowledgeable of the location of every wound and drainage tube is very important. The practical nurse must practice aseptic techniques in collecting specimens, avoiding accidental contamination of the specimen, and the spread of infection to others.

a. Procedures for Collecting/Submitting a Wound Culture Specimen From a Postoperative Patient.

(1) Wash hands and assemble all equipment.

(a) Antiseptic swabs.

(b) Sterile culturette tube or sterile applicator with a culture medium tube.

(c) Exam gloves.

(d) Sterile gloves.

(e) Sterile dressings, as appropriate.

(f) Waste receptacle.

(2) Verify the physician’s order.

(3) Identify and approach the patient, explain what you are going to do, and gain his cooperation.

(4) Provide adequate lighting and for patient’s privacy.

(5) Wash your hands.

(6) Position and drape the patient as indicated for the site of the specimen collection.

(7) Put on exam gloves.

(8) Remove patient’s wound dressings, if appropriate, and discard.

(9) Remove exam gloves.

(10) Open sterile supplies using aseptic technique.

(11) Apply the sterile gloves.

(12) Cleanse the skin around the area to be cultured with antiseptic swabs to prevent contamination of the specimen by surface bacteria.

(13) Obtain the specimen. The break stick technique or the culturette method may be used.

(a) Break stick technique.

1 Remove the cap from the culture tube and hold the cap in your nondominant hand, maintaining sterility of the inside of the cap.

2 Using sterile applicator, swab the exudate from the site.

3 Insert the swab portion of the applicator into the sterile culture tube.

4 Break off the upper portion of the applicator.

5 Replace the cap on the culture tube.

(b) Culturette method.

1 Remove the cap with the sterile applicator attached from the culturette tube.

2 Swab the exudate from the site.

3 Replace the swab in the culturette tube, securing the cap.

4 Turn the culturette tube cap down.

5 Crush the ampule in the bottom of the tube by squeezing it between your index finger and thumb at midpoint.

6 Push the cap down to bring the swab into contact with the culture medium.

(14) Redress the patient’s wound with the appropriate dressing, if necessary.

(15) Remove the sterile gloves.

(16) Label the specimen container.

(17) Reposition the patient comfortably.

(18) Discard equipment or return it to the appropriate area.

(19) Wash your hands.

(20) Complete the laboratory request slip, if not already prepared.

(21) Send the specimen to the laboratory immediately. The specimen can be destroyed if it is not plated to a culture medium at once.

(22) Record procedure in patient’s clinical records.

(a) DA Form 4578, Therapeutic Documentation Care Plan –Nonmedication.

(b) SF 510, Nursing Notes.

1 Time, site, and method of specimen collection.

2 Appearance of the patient’s wound site and the specimen collected.

3 The patient’s tolerance of the procedure.

4 Disposition of the specimen.

5 All patient teaching done and the patient’s apparent level of understanding.

b. Maintain the Postoperative Patient’s Wound/Nasogastric Drainage Tubes. The nurse must connect and maintain the tubes to the ordered suction device, must avoid introduction of microorganisms into wound or drainage system, and must also avoid dislodging tubes. The procedures are as follow.

(1) Wash hands and assemble all equipment.

(a) Suction unit (Hemovac, electric or wall vacuum continuous unit, or intermittent suction).

(b) Graduated container.

(2) Verify physician’s order.

(3) Identify and approach the patient, explain what you are going to do, and gain his cooperation.

(4) Provide for the patient’s privacy and position the patient to facilitate access to the drainage tube.

(5) Provide adequate lighting.

(6) Wash your hands.

(7) Activate the appropriate/ordered tube drainage/suction unit.

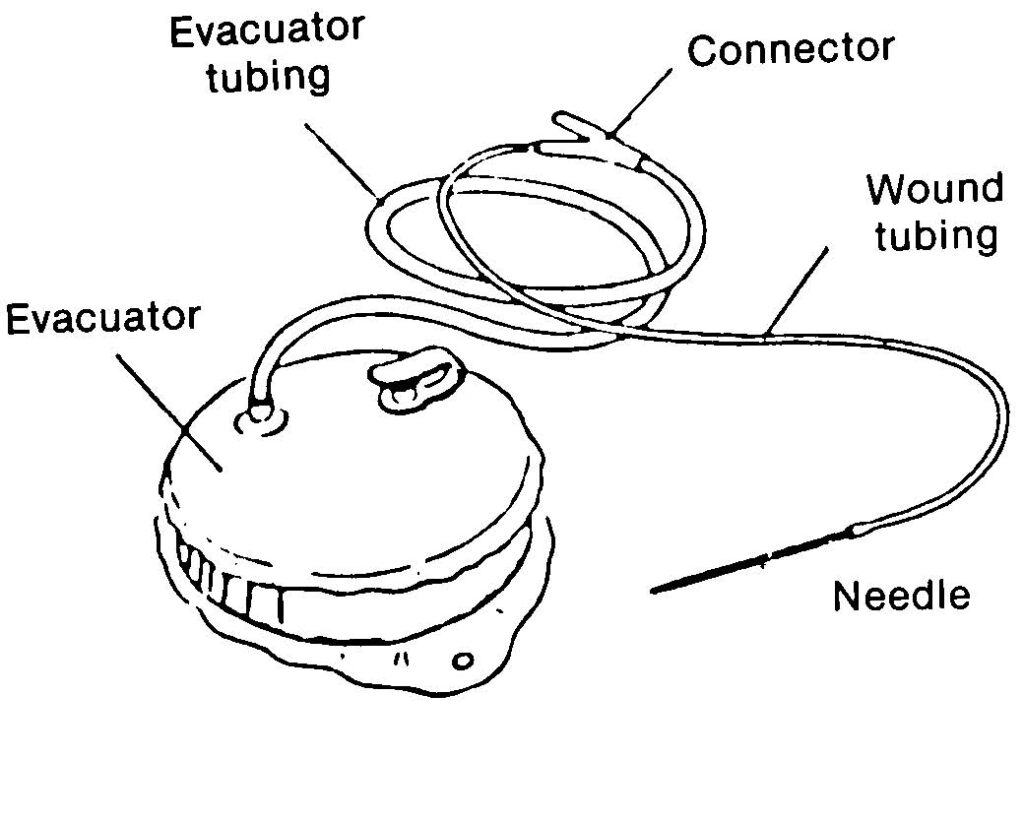

(a) Hemovac (wound drainage tube suction) (see Figure 4- 7).

1 Remove the plug cap aseptically and place the portable suction unit upright on a firm surface.

2 Compress the suction unit as flat as possible (see Figure 4-8).

3 Replace the plug cap immediately (see Figure 4-9).

4 Position the suction unit to prevent kinking of the tubes or dropping of the unit.

5 Observe the suction unit for proper compression and patency.

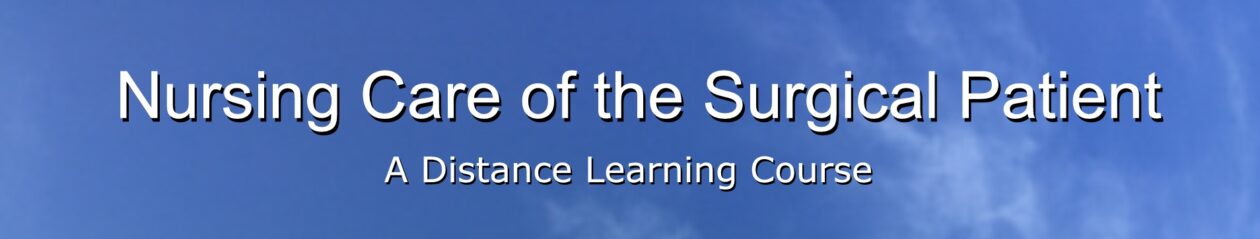

(b) Electric or wall vacuum continuous or intermittent wound/gastrointestinal suction unit (see Figures 4-10 and 4-11).

1 Plug the unit into an electrical outlet or attach to a wall system vacuum.

2 Connect the suction tube to the patient’s drainage tube, using aseptic technique.

3 Tape the connection. Ensure that the tubing is not pulling on the drainage tube.

4 Turn the suction unit on “Low” unless specifically ordered differently.

5 Observe the suction system for proper functioning.

(8) Empty the drainage collection device, as necessary.

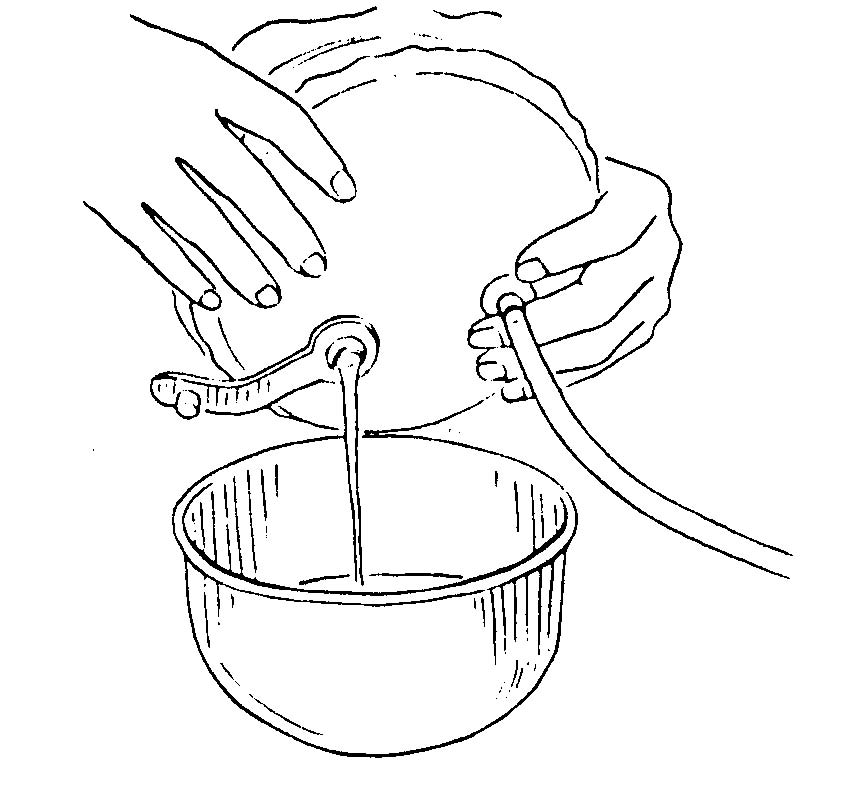

(a) Hemovac.

1 Remove the plug cap, using aseptic technique.

2 Invert the suction unit over the graduated container and empty the contents (see Figure 4-12).

3 Return the unit to an upright position and reactivate the unit. Measure and read the drainage and discard.

(b) Electric wall vacuum continuous or intermittent wound section unit.

1 Turn the suction unit off.

2 Empty the drainage bottle.

3 Measure and record the drainage and discard.

4 Reattach the drainage bottle.

5 Turn the suction unit on and observe for proper function.

(9) Discard equipment or return it to the appropriate location.

(10) Wash your hands.

(11) Record procedure and report significant observation to the Charge Nurse.

(a) Type of wound catheter and suction.

(b) Amount, color, characteristics, and odor of drainage.

(c) The patient’s reaction to the procedure.

(d) Function of suction system.

(e) Any observations of the wound area or dressing.

(f) All patient teaching done and the patient’s apparent level of understanding.

c. Remove Sutures from a Postoperative Patient’s Surgical Wound. The nurse must avoid introduction of skin surface contaminants into wound site and interference with wound healing. He must also avoid causing unnecessary pain/discomfort for the patient.

(1) Verify the physician’s order.

(2) Wash hands and assemble needed equipment.

(a) Prepackaged suture removal supplies/equipment.

(b) Antiseptic pledgets.

(c) Smooth forceps.

(d) Scissors

(e) Dressings/sterile wipes.

(f) Hydrogen peroxide (as required).

(3) Identify and approach the patient, explain what you are going to do, and gain his cooperation.

(4) Remove the patient’s wound dressing to expose suture line.

(5) Cleanse the stitch area carefully and thoroughly with hydrogen peroxide.

(6) Use hydrogen peroxide to remove dried secretions or encrustations, as necessary.

(7) Grasp the knot of each suture with a pair of smooth forceps and

gently pull upward to pull stitch away from the skin (see Figure 4-13).

(8) Cut the shortened end of each stitch as close to the skin as possible and pull each stitch free from the wound.

(a) Allows the stitch to be pulled free of wound so that when stitch is removed, only that part of the stitch which is under the skin touches the subcutaneous tissues.

(b) No segment of the stitch that is on the surface of the skin should be drawn below the skin surface. That could introduce skin surface contaminants subcutaneously with risk of infection.

(c) If the suture does not pull free when cut or is embedded into healed suture line, report immediately to the Charge Nurse or to the physician for assistance.

(d) For continuous suture removal, cut the suture at each skin orifice on one side and remove suture from the opposite side. The objective is to avoid subcutaneous contamination.

(9) Pat the suture removal sites with an alcohol sponge.

(10) Reapply dressing as appropriate.

(11) Record procedure and report significant observations to the Charge Nurse.

(a) Wound site condition.

(b) Surface healing.

(c) Evidence of infection.

(d) Poor wound adhesiveness.

GENERAL NURSING IMPLICATIONS OF THE POSTOPERATIVE PATIENT

4-18. GENERAL

The length of time a patient needs to recuperate from a surgical experience depends on the patient’s preoperative physical and mental preparation, the type and magnitude of the surgical procedure, and the multiple factors involved in the postoperative recuperative periods.

4-19. GENERAL POSTOPERATIVE NURSING TASKS

In helping the surgical patient to return to his maximal possible state of health, in addition to your specific duties, you must also perform the following.

a. Monitor the patient’s vital signs as ordered.

b. Report the patient’s elevated temperature and rapid/weak pulse immediately to the Charge Nurse. As mentioned before, this may be an indication to an infection.

c. Report the patient’s lowered blood pressure and increased pulse to the Charge Nurse. This may be an indication to hypovolemic shock. d. Administer analgesics to the patient as ordered.

e. Apply all nursing implications related to the patient receiving analgesics (narcotic or not).

f. Participate in nutrition therapy with the health team. You will be providing nutrition to the postoperative patient according to the patient’s condition and doctor’s order.

g. Apply all nursing implications related to diets — serving, recording intake, and food tolerance.

h. Maintain and administer all IV fluids and IV sites per doctor’s orders and infections control SOP.

i. Prepare the patient and family for discharge.

(1) Supply written instructions for:

(a) Wound care.

(b) Surgical/clinic appointment.

(c) Phone numbers of related clinics.

(2) Coordinate with team leader for CMS supplies needed for wound care and prescriptions for self administration.

(3) Document discharge in the Nursing Notes per ward SOP.