Forceps are used to assist in labor and delivery.

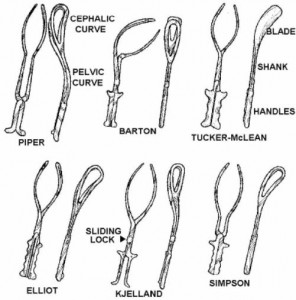

Forceps delivery is considered an operative obstetric procedure. The commonly used forceps have a cephalic curve shaped similarly to that of the fetal head. A pelvic curve of the blades conforms to the pelvic axis (see figure 5-3).

The blades are joined by a pin, screw, or grove arrangement. These locks prevent the forceps from compressing the fetal skull.

a. Indications for Use.

(1) Maternal. To shorten the second stage in dystocia, when the patient’s expulsive efforts (inability to push) are deficient (for example, she is tired or has been given spinal anesthesia), and when the patient is endangered (for example, cardiac decompensation).

(2) Fetal. To rescue a jeopardized fetus (for example, premature labor or fetal distress close to delivery).

b. Complications of Forceps Delivery.

(1) Maternal.

(a) Lacerations of the vagina and cervix, predisposing to hemorrhage and infection.

(b) Rupture of the uterus.

(c) Injury to the bladder or rectum.

(2) Fetal.

(a) Cephalohohematoma.

(b) Brain damage and intracranial hemorrhage.

(c) Skull fractures.

(d) Facial paralysis.

(e) Cord compression.

c. Conditions for Forceps Delivery.

The following conditions must occur for successful forceps delivery.

(1) Fully dilated cervix. Severe lacerations and hemorrhage may ensue if a rim of cervical tissue remains.

(2) Head engaged. The extraction of a mature fetus with a “high” (unengaged) head usually is disastrous.

(3) Vertex presentation or face presentation. Other presentations require wider-than-average pelvic diameters.

(4) Membranes ruptured. This will ensure a firm grasp of the forceps on the fetal head.

(5) No cephalopelvic disproportion. If there is engagement, there must be no outlet contracture or gross sacral deformity.

(6) Empty bladder and bowel. This will avoid laceration and fistula formation.

d. Levels of Forceps Application.

The station of the fetal head determines the level of forceps application and, generally, the relative difficulty to be expected in forceps operations.

(1) High forceps. The biparietal diameter of the vertex is above the ischial spines (the head has not yet engaged) when the forceps are applied. High forceps delivery is an exceedingly difficulty and dangerous operation for both patient and fetus and is rarely done.

(2) Midforceps. The vertex is at the ischial spines, almost to the ischial tuberosities on application of the forceps. The delivery often is difficult, depending on the size of the vertex, its position, and the pelvic architecture and diameters. A cesarean birth is preferred to a potentially difficult midforceps delivery.

(3) Outlet (low) forceps. Outlet or low forceps is used when the fetal head is on the perineal floor (visible or almost so) and internal rotation may have already occurred, so that the fetal head lies in a direct anteroposterior position.

e. Nursing Interventions.

(1) Obtains forceps designated by the physician.

(2) Checks, reports, and records the fetal heart rate before forceps are applied.

(3) Informs the patient that the forceps blades fit like two tablespoons around an egg. The blades come over the fetus ears.

(4) Rechecks, reports, and records the fetal heart rate again before traction is applied after application of the forceps. Compression of the cord between the fetal head and the forceps would cause a drop in fetal heart rate. The physician would then remove and reapply the forceps.

(5) Give support to the patient.

(6) Observe for signs and symptoms of complications.

(7) Assess the newborn for indications of injury.